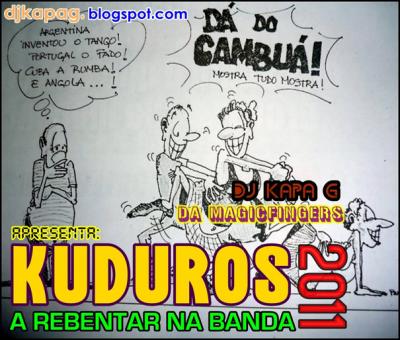

This article explores the role of Kuduro, the popular Angolan electronic music and dance style in the process of updating the national Angolan identity called angolanidade to the conditions of the new millennium.

Angola has recently become an important player in the global economy due to its wealth of oil and diamonds, after having been in the news mainly because of the atrocities of an enduring civil war. Most of the country’s population lives in Luanda, a metropolis of about seven million inhabitants. In this both utopian and nightmarish urban setting one of the most intriguing musics of the African continent has been born: kuduro. In this article we explore the role of this popular Angolan electronic music and dance style in the process of updating the national Angolan identity called angolanidade to the conditions of the new millennium.

French DJ Frédéric Galliano's CD-Albums Kuduro Sound System (produced in Luanda in 2005 and 2008, first with Angolan artists and singers like Dog Murras, Tony Amado, Zoca Zoca, Pai Diesel, Pinta Tirru and Gata AGressiva, and second with various underground artists) catapulted kuduro’s sound onto club dancefloors all over the world. Since then kuduro has been debated in the North American and European music press and blogosphere. This field of discourse is not primarily concerned with Angolan issues. Here, kuduro has been discussed mainly under the umbrella of global ghettotech or an afro-futuristic critique thereof (Goodman 2010). The concept of global ghettotech stresses the origin of disparate musical styles in supposedly similar deprived urban areas around the Atlantic whereas an afro-futuristic reading lets go of notions of authenticity and roots in favor of narratives of aquatic or outer spaces, viruses and a focus on technology with transgressive powers (Eshun 1998).

We shift this focus to investigate kuduro’s role in the process of re-shaping angolanidade today, arguing, that performative acts in kuduro’s sound, style and demeanour are constituting a new angolanidade. This angolaness is constituted in different contexts of the local, the international and the virtual. We suggest that in its most recent incarnation angolanidade as reflected in and constructed through kuduro is not only digital, but also transnational and closely tied in with a) international systems of popular culture such as hip hop semiotics of dance moves and gang affiliations, b) global electronic music culture as well as c) local Angolan cultural forms like the rich popular musics from the 1950s onwards like semba, kizomba or carnival dancing. Semba as a rhythm or style is regarded as that which makes a a piece of music sound distinctly Angolan, for Moorman semba as an umbrella term includes the social components as well as a variety of genres (Moorman 2008, 7). Both semba and kizomba are usually couple dances.

Information for this article have been collected from different perspectives. Nadine Siegert, a cultural anthropologist has done fieldwork for her PhD thesis in Luanda and Lisabon in 2007, 2008 and 2009. While working primarily on the contemporary art-scene, popular music has always been an important sideline in her work. Stefanie Alisch, a musicologist and DJ is preparing a PhD on kuduro and is planning to do field research in Lisbon and Luanda in 2011. Both researchers have established contacts with actors of different platforms of the kuduro-scene (for the concept of platforms, see below). A major part of the research has also been conducted on the internet. Tracking news in various online platforms provides an invaluable but also never-ending source of data. For this article, we develop our argument by utilizing a close reading of video material and contextualizing this with Angolan history and the role music and popular culture played in it.

Angolanidade – the Role of Popular Music in Angolan History

1.1 Historical Background

The present situation in Angola is the result of about 500 years of Portuguese (and Dutch) colonialism, the impact of slave trade and a recent history of wars. Angola had been a Portuguese colony for 400 years, been regarded as Overseas Province to Portugal since 1951, a mere appendix governed by a geographically and culturally remote Estado Novo («New State»). This military regime under António de Oliveira Salazar was one of Europe’s last authoritarian dictatorships. In a time when other African colonies had already become independent, Portugal kept its colonies until 1975. This led to a brutal liberation war in Angola (1961-1974). Independence came as a result of Lisbon’s carnation revolution. It was succeeded by a civil war between the main liberation movements, the Movimento Popular para a Libertação de Angola («People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola», MPLA, today’s government party MPLA, founded in 1956) and the oppositional party União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola («National Union for the Total Independence of Angola», UNITA, founded in 1966 and led by the rebel leader Jonas Savimbi). The civil war was often regarded as one of the most prominent Cold War proxy wars. It ended in 2002 with the death of Savimbi, and devastated land, economy and social structures.

Many individuals and their cultural traditions were scattered about the country or forced into exile. At the periphery of Angola’s capital Luanda large informal neighbourhoods called musseques continue to grow as a result of the intra-Angolan migration during and after the civil war. Musseque means «sandy area» in Kimbundu, one of Angola’s main languages. They are the counterparts to terreno asfaltado, the «asphalt areas».

With Angola holding one of the highest rates of landmine injuries per capita in the world, amputees are a common sight in the streets of Luanda (Vierke 2008). However, in the postwar years the capital Luanda developed a second face due to the growing economy, relying on natural resources such as oil and diamonds as well as South-to-South business arrangements. With tower blocks and real estate prices soaring Luanda is bursting at the seams and might soon be included in the list of mega-cities (Davis 2006, Rühle 2008).

1.2 Angolanidade, Music and Politics

Angolanidade (roughly translated as angolaness) can be described as Angolan cultural patriotism. Angolanidade speaks of a sense of identity both rooted in local cultural practices and in cosmopolitanism, thus being a «rooted cosmopolitanism» or «cosmopolitan patriotism» as defined by Kwame Appiah (Appiah 1996). Since the time of the liberation war it became a metaphor for cultural autonomy of the Angolan population fighting against the colonial oppressors. The concept of angolanidade can be traced back to the late 19th century. A free press that published texts of both, Afro- and Euro-Angolans, was budding then. In the 20th century it became inspired by the ideas of the négritude, a cultural ideology developed by African and Caribbean intellectuals living and studying in France and later becoming the basis for the Cultural Policy of independent francophone states like Senegal. Négritude emphasized the cultural relevance of African literary and cultural output. It was adapted to the Angolan context by intellectuals and artists like the poet Viriato da Cruz. He started the journal A Mensagem («the message») in the 1940s. As the mouthpiece of the first native Angolan literary and political movement Os jovens intellectuais («The Young Intellectuals»), the magazine promoted the slogan Vamos descrobrir Angola («Let’s discover Angola»). Along with other members of Os jovens intellectuais such as Agostinho Neto or Mário Pinto de Andrade, Viriato da Cruz went on to become a leader of the MPLA.

US American historian Marissa Moorman provides a comprehensive overview of the political and social role of music and popular culture within this context. She explores how Angolan national consciousness was created and negotiated through music and cultural production in general. (Moorman 2008): «Lyrics and the music were also about saying «yes»: affirming and producing angolanidade and, in the process, marking out a culturally autonomous space forged and expressed in African-owned and -operated clubs, in music festivals, in dress and dance and attitude» (Moorman 2008, 112).

Music became explicitly political in the 1950s. At this stage the Angolan liberation movements formed in exile in the neighbouring countries like both Congos as well as in Europe. From there the liberation war started in 1961. Moorman emphasizes that the urban population actively imaginated an independent nation, which she sees as an important step in the indepence process. Angolanidade stood primarily for the cultural movement in the capital Luanda. A rather high percentage of the population in the musseques comprised of mestizos, an ethnically and culturally mixed population. They regarded themselves as the cultural elite engaging strongly in political, social and cultural activities, and formed the core of the liberation movement MPLA.

One of the most important bands promoting Angolan patriotism was Ngola Ritmos («Angola Rhythms»), founded in the late 1950s. They supported the guerilla fight with their songs, and some of its musicians were also active members of the liberation movement MPLA. In 1959 and 1960 two of the Ngola Ritmos’ members–Carlos Liceu Viera Dias and Amadeu Amorim–were imprisoned in the infamous Tarrafal jail on the Cape Verde islands for more than ten years. The band’s singer and guitar player José Maria dos Santos was sent into exile in the provincial town of Lubango. António Ole’s documentary film O ritmo do Ngola Ritmos («The rhythm of Ngola Ritmos», 1978) relates the story of their reunion in 1977.

Moorman describes the years 1961-1974 as the «Golden Years» of Angolan music. In that time, Angolans developed the nation and created expectations about nationalism and political, economic and cultural sovereignty through popular music produced in Luanda’s musseques. In musical styles like semba and later kizomba, the musicians in the musseques played and danced their nation into being. Combining international trends of popular music of that time like Latin-American and Caribbean rhythms with Angolan traditional songs and folklore, the musicians created angolanidade primarily by singing in national languages like Kimbundu and Umbundu and using local instruments. At that time the MPLA’s radio programme Angola Combatente («Fighting Angola») was broadcasted from Congo-Brazzaville. At both sides of the Congolese-Angolan border people would absorb its political and cultural messages. Through the airwaves people in the musseques were emotionally united with the guerilla fighters at the front of the liberation war. Thus, Angola’s self perception gradually changed from being a mere appendix to Portugal, an overseas province, to that of a country in its own right. In this process music served as a template for independence.

After the independence in 1975 things took a turn for the worse in terms of cultural productivity. The years following independence until 1989 were somewhat a hiatus due to the musicians’ forced alignment to Angola’s official socialist cultural and educational policy. The drastic change of the cultural atmosphere in Luanda after 1975 is also reflected in the increasing emigration of artists during that time. The MPLA, resistance movement turned ruling party, started instrumentalizing music for their purposes. From a felt unity and the desire for independence the country became fragmented and culture became politicized. Music was used by the young Angolan state as a nation-building tool. This lead to a strict censorship. In 1977 three musicians were killed and their music was banned from the radio for over a decade.

«Musicians remained important to social and political life but they could no longer play the music of the past. The musical agenda was now a nationalist revolutionary one in which state developmental and political priorities held sway. As musicians describe it, the state co-opted music for its own political ends; something they describe as the music becoming politicized» (Moorman 2009).

This historical process shows, that the period of euphoria and power of utopic vision in Angola was not in in the years right after independence but in the time of late colonialism just before it. In certain aspects, present day Angola and its economic and cultural boost after the civil war, along with the euphoric emotional subtext of embarking on a journey into a promising future, seems to have more in common with this late colonial period of struggle for independence than with the time when independence had actually been achieved.

In the following chapters we look into the ways through which musical activities still constitute a large part of the Angolan patriotic self-concept, even if musical and dance styles have evolved drastically since the struggle for independence.

Kuduro

2.1 Kuduro as a Phenomenon

Kuduro is a popular sound and dance that was developed in Luanda and Lisbon around 1990 and continues to mature. The electronically produced tracks contain, amongst other elements, Angolan styles like semba and kizomba, rhythms akin to upbeat Caribbean soca as well as techno and house beats. The lyrics are mostly rapped in Angolan Portuguese and in Calão, a creole of Kimbundu and Portuguese that is typical for Luanda (Siegert 2008). The raps are mostly delivered in half time against an upbeat tempo around 130-140 BPM. This way a certain tension that is typical to kuduro in general is created in the area of sound.

2.2 Kuduro Dance

Kuduro sound and dance are inseparable. The dance contains elements of at least three areas: a) popping and locking, break-dance, headpins and power moves from hip hop b) traditional Angolan and carnival dance movements c) graphic theatrical movements such as crawling on the ground as if in a battle, dancing on the thighs as if the legs were amputated, dancing with legs turned inwards as if on crutches, dancing on crutches, with missing limbs or mimicking media images of «starved Africans». While constructing a new order out of the above elements kuduro dance at the same time constantly destabilizes this order when dancers execute movements such as slapping themselves in the face and falling flat on the ground as if shot.

2.3 Kuduro Distribution and Media

The main distribution channels for kuduro in Luanda are minibus taxis, called candongueiros. Kuduro is performed on street corners when the candongueiros turn in to mobile sound systems (Siegert 2008). In recent years big kuduro events with sponsors and media coverage as well as kuduro performances in chique night clubs have become more common. Kuduro had been circulating in informal distribution structures of candongueiros, street vendors and on the internet with little access to mainstream media for nearly 20 years.

During the mid-1990ies, DJ Sebem’s show on Radio Luanda, where he frantically MCed over instrumental tracks, helped to spread the sound of kuduro all over Luanda.

In 2006, the Lisbon based Buraka Som Sistema‘s single Yah! exploded on the dancefloors of hip clubs around the world. Since then, kuduro dance performance videos find an increasing audience on internet video platforms like YouTube. The videos range in quality from MTV standard to barely recognizable mobile-phone footage. As with most music styles, various weblogs and sharehosting websites offer kuduro for download in mp3 format.

In 2009, DJ Sebem started his national TV-show Sempre a subir («Always on the Rise»). DJ Sebem still functions as kuduro’s fashion role model number 1, always rocking the most colorful and innovative outfits (Siegert, 2008). The TV show’s main feature are interviews between Sebem and current kuduro stars. A staple of these conversations is the topic of beef. Angolan Portuguese borrowed the term from US American hip hop culture where it refers to aggressive competition between gangs or individuals. Sometimes beef is purely metaphoric, sometimes physically violent or lethal. Watching Sebem chat casually about beef to his guests suggests kuduristas use it as a playful marketing tool. Relations of distrust and rivalry between the various musseques are discussed along the lines of which kuduro artists should best represent a certain neighborhood.

In the following clip Nagrelha, a member of the kuduro group Os Lambas («the adversities»), criticizes the kudurista Puto Prata for having abandoned his country and being no longer able to act as a representative of the neighborhood Rangel.

Angolanidade in Kuduro

Kuduro is practised on three platforms: Luanda, Lisbon and dance floors around the world, the latter including the Angolan diaspora communities as well as high end nightclubs in London, New York or Berlin. We borrow the idea of «platform» from the art exhibition documenta 11 curated by Okwui Enwezor in 2001. The platform model aims to avoid discussing questions of the local and the global which would distract from discussing kuduro in the light of angolanidade in this article.

The cultural anthropologist and musicologist Gerhard Kubik stressed the importance of the lively cultural transfer in the triangle of Lisbon, Luanda and Brazil that has been in effect for more than 400 years. According to him, música popular (popular music) which popped up in one of the three angles could be heard in of the other places after not more than six weeks (Kubik 1979). Early transnational actors and traveling musicians were the first ones to transport the intangible goods. Later radio, cassettes, videos, CDs and today the internet catalysed this exchange.

Our analysis here contains a discussion of platform I – Luanda, respectively its representation on the internet, while also briefly touching on the platforms of the international club-scene and Lisbon.

3.1 Platform I – Luanda

In Luanda, kuduro is mostly produced in basic studios in the musseques on the outskirts of the capital. Like the musical movements at the time of the liberation war and independence, kuduro was born in the musseques. It seems that a narrative of an origin within the ghetto is key to kuduro artists. Whereas Bairro Operario («worker’s neighbourhood») functioned as the hotspot for 1960ies música popular, today the musseques of Rangel, Sambizanga, Viana and Cazenga are referenced as the important centers of kuduro production. In an upcoming field trip we shall more thoroughly research the specific situations of production studios and distribution networks in Luanda.

The first show of a the national TV series Janela Aberta («open window») exploring the evolution of kuduro can be seen here:

In Angola, the conditions of kuduro production and its topics have changed significantly during the past years. Today, many stress the fact that the music is now completely produced in Luanda. Studios like Ghetto Produções («Ghetto Productions») own the sufficient equipment to produce «Kuduro – Made in Angola» – a label entertaining notions of authenticity and realness. Angolan kudurista Killamu actually lives the realities that Lisbon based Batida (see chapter 3.2) and Les Princes de Kuduro («the kuduro princes», see chapter 3.3) refer to. For Killamu, it is important to mention that the new kuduristas after Tony Amado and Sebem have revolutionized the music by adding rhymes and lyrics, thus making kuduro more versatile and leaving simple party animation behind. He comments on the poor working and living conditions he finds himself in, and relies on Ghetto Produções, which is located in the middle of one of Luanda’s musseques. His critique poses a sharp contrast to Batida’s statement, that kuduristas approach their problems with verve and positivity.

Until today music is also exploited for propaganda by politicians, and the production itself is bound up into a patronage system. Dog Murras, one of the most popular kuduristas of the last years was for example sponsored by a general from the Angolan military (Moorman 2008, 192).

In the following video as well as in his visual self representation Dog Murras takes a clear position toward a new version of angolanidade. On his album covers and in Jorge António’s documentary Kuduro – Fogo no Museke («Kuduro – Fire in the Museke») (2007) the big guy appears with a Che Guevara tattoo, silver ear-pins and D&G sunglasses, presenting himself as an Angolan national musician of the new generation. In 2005, Dog Murras started wearing the flag motif exactly at the moment when a national competition for a new design was underway, and the party issued a statement to treat this national symbol with more respect (Moorman 2008, 194). Thus, Murras’ performance can be interpreted as an act of personal appropriation of this national symbol rather than Murras being under the whip and mainstreaming. He brought patriotism back to the people in his own particular way, enabling them to wear the national symbols with pride and as a fashion statement. Dog Murras reached fame during the first years after the civil war, but it seems that his popularity among the younger generation has dwindled. Murras integrates a variety of popular musical styles in his kuduro and relates to the problems of his society in his lyrics. According to an Angolan informant it seems that Dog Murras has fallen from grace and re-located to Brazil.

Today in June 2011, Dog Murras seems to have returned to Angola on a mission to run KUDISSANGA music school. Here, children are encouraged to discover their cultural roots of angolanidade through music. Social projects based on essentializing notions of African music and culture are common in Salvador da Bahia, the most prominent ones being Olodum or Pracatum. These projects often entail drumming and dancing lessons, a certain afro-centric styling deploying kauri shells as well as t-shirts with motivational slogans. On June 12th 2010, Dog Murras announced the upcoming release of his single «Angolanidade», reflecting the currency of the topic of this article.

Recently kuduro performers seem to align their wardrobe with a global youth dress-code of thick rim glasses, skinny jeans, wild print hooded tops all in strong primary colors, or even the tongue in cheek preppy style of London Shoreditch. While the setting and narrative of the videos still emphasize street-smartness and life in the informal neighborhoods, kuduristas appear ever more stylish, using all kind of digital accessories. In their video clip Sobe («he or she moves up» or «move up!»), for example, a member of the group Os Lambas are sporting the white headphones cables of an iPod. Talking names are part of this performance, like Puto Prata («silver guy»), Puto Portugues («portuguese guy»), Puto Lilas («purple guy») or Nacobeta. Kuduristas like President Gasolina («president gasoline») and Prince Ouro Negro («prince black gold») have even invented their own diction, changing and exaggerating some parts of the words: «Nos temos uma maneira de falar e uma maneira de vestir. Porque existe kuduro e existe kudurista.»

The animosities between the kuduristas in the various musseques Viana, Rangel, Cazenge and Sambizanga seem to increase. Kuduristas start to publicly consider themselves reis (kings) commanding and thus responsible for their ghetto where making music is called a luta (the fight). At least rhetorically the borders between affiliation with kuduro and running with the gang of a famous kudurista in a specific musseque seem to blur.

«O kuduro representa o gueto.»

«Agressive» appears in some female kuduristas names (Gata Agressiva, Tuga Aggressiva) and is regarded a necessary feat for success. Carga («charge»), a certain intense impact in vocal delivery and performance is key here.

Other kuduristas appear on the TV show as proud representatives of their ghetto or even their province. The female Kudurista Muana Po came the long way from Saurimo in the far eastern province Lunda-Sul to explain to Sebem the meaning of her artist name. Muana Po is one of the most familiar masks of the Chokwe tradition. It represents a young woman and is danced at festivals for entertainment. Sebem knows at least that it is something «traditional». This shows that Chokwe tradition became part of the national cultural archive, even if the knowledge about the actual background is not very deep. Yet another reference to angolaness is the importance given to the use of national languages like Kimbundu. There are only a few examples of kuduro songs with fragments of Kimbundu. Even if this is not a common practice, it is highly acknowledged.

To sum up, on its first platform Luanda, kuduro is deeply integrated into the social-historical context and changes its modes and visual codes according to the changes within the society itself and changing global fashion. It can thus be regarded as a flexible tool to deal with fast paced urban life in Luanda – both hardships and joy.

3.2 Platform II – Lisbon

Around 30.000 Angolan civil war refugees settled in Lisbon, especially in outskirts such as Amadora and Queluz. This is where kuduro developed its second centre and a distinct style called kuduro progressivo («progressive kuduro»). This style contains stronger elements of techno, dubstep or post hip hop dance music and prides itself in being more elaborate on the technical side of musical production. The main representatives are Buraka Som Sistema («Buraka Sound System»), who released their debut album Black Diamond in 2008. Since the summer of 2007 they have been extensively touring festivals and clubs in Europe and the U.S. In 2008 they released the single Sound of Kuduro starring the Tamil British rapper and performer M.I.A.. The video can be seen here:

Returning to the kuduristas of Angola, in 2007 Buraka Som Sistema travelled to Luanda for the production of the song Sound of Kuduro and the accompanying video clip. The clip «Sound of Kuduro» opens with images of the band members driving through Luanda, saying: «We made it…. we are here…. pela primeira vez (‹for the first time›)». In this video kuduro artists from all three platforms are brought together in what is regarded as the source of the style, thus the clip can be seen as an attempt to re-essentialize or the work of Buraka Som Sistema. Discussion of this band centers on the «authentic» cultural knowledge of the Angolan producer Conductor, who actually grew up in Lisbon, and the Angolan-born MC Kalaf. They are known for bringing extensive knowledge of kuduro music to the Lisbon music scene. In fact only Kalaf lived in Angola during his childhood years, but still Angola and its music serve as a blueprint for the group’s musical concept: a fusion of Angolan kuduro with 21st century bass heavy club music. Buraka Som Sistema displays a playful approach handling angolanidade. In their recent single «Restless» as well as solo projects like J-Wow they are leaning towards more abstract electronic styles with less emphasis on obviously Angolan sound elements, using English lyrics.

After Buraka Som Sistema new bands have followed in Portugal. The group Batida consists of the two former hip hop musicians Ikonoklasta (Luaty Beirao) and DJ Mpula (Pedro Coquenão) with Kudurista Sacerdote as MC. Ikonoklasta was born in Angola and was part of the Angolan-Portuguese hip hop group Conjunto Ngonguenha together with MC K, Conductor and others (Lança 2007). He is also part of the association Radio Fazuma and producer of the documentary on the young Angolan music scene E dreda ser angolano («It’s cool to be Angolan»). In comparison to Buraka Som Sistema, Batida project themselves as a group who strongly relate to Angolan culture. Batida’s live show features dancers moving at the front area of the stage while DJ Mpula operates sound equipment in the back. The dancers wear bast skirts or bast masks with a wood carved facial part that cover face and torso. These outfits evoke vague notions of Angolan traditions like rural initiations schools that involve mask dances (Kubik 1981). See Batida in an interview here:

Pronouncing «dance» in English not Portuguese, they explain the intended fusion of universal club dance culture with Angolan music from the 1960s and 1970s.

«Recuperam sonoridades de 60s e 70s, sem nostalgia mas com respeito.»

Attire wise Batida allude to angolanidade and africanness as well. Ikonoklasta sports t-shirts with the omnipresent Angolan flag or Chokwe symbols. Both Mpula and Ikonoklasta use animal print headwear that echo notions of safari garb. In a similarly essentializing fashion Batida discuss their CD Dance Mwangolê («Angolan Dance»). MC Ikonoklasta explains that they strive to «guardar pureza da musica angolana» («save the purity of Angolan music») by creating this Angolan dance music. Also their videoclip Bazuka begins with references to Angolan history such as the famous queen Rainha Ginga.

Rainha Ginga’s picture is inserted with a statement of a young kudurista saying «Me, who drafted me, ain’t my mother nor my father…». Nextwe see found footage from the Portuguese Radio and Television (RTP) archive showing a marching army, shots of political personalities like Salazar and footage of traditional dances. In bright colours scripts are pasted over the images asking questions like «quem me rusgou (who swooped me)?», «Direita (right)?», «Esquerda (left)?» – together with a strong and pushing kuduro beat.The second part of the clip shows further images of the civil war and the current situation. Both the roles of today’s president Eduardo Dos Santos and of Jonas Savimbi – the former warlord and leader of the UNITA – are questioned, relating back to the first question: «Who drafted me? Not my mother» (Dos Santos), «not my father» (Savimbi). Subsequently, pictures of kuduro dancers and masked dancers in rural settings are edited one after the other, showing the similarities in the dance styles. The last part of the clip shows a short interview with a young man talking about his reminders of the war – two pieces of shrapnel in his body. This might be interpreted as an answer to the question «Who drafted me for the war?» It was the war itself. Depictions of traditional dances and percussion during the last part of the clip may also lead to the conclusion that it is neither the biological family nor the politics who draft a person, but rather the culture. In this case the Angolan culture is in focus which leads us back to angolanidade. In name, lyrics and imagery Batida construct explicit references to Angolan history and the wars by depicting Angolan heroes (Rainha Ginga) or inserting found footage of the liberation war. The imagination of a strong and potent nation in spite of or maybe even because of the war is alluded to here. Batida authenticate its work not unlike Buraka did in the Sound of Kuduro. Where Buraka Som Sistema refers to the urban contemporary Angola, Batida resorts to using references evoking an earlier and more mysterious Angola. The band positions itself problematically at a nexus within a field of traveling signs where they have access to both technological and cultural material.

Os Makongo («the congolese»), a third Lisbon based kuduro outfit, formed around female MC Pety who had worked with Buraka Som Sistema during their early years. In the clip below, she stresses that Os Makongo are the kuduro band in Lisbon that is known for consisting of Angolans. Pety playfully slaps one band member around the head to make him say that he comes from the notorious Luandan neighborhood Cazenga and then burts out laughing:

The fact that the molested rapper is rather light-skinned and cannot bring himself to make such claims of a ghetto past makes this statement even less believable. It looks as if Os Makongo are mocking the way other Lisbon based kuduro bands are trying just a little too hard to come across as authentically Angolan. Os Makongo on the other hand stress that they are fusing all kinds of dance genres like hip hop and euro dance with kuduro. Try as he might, in the above snippet from Sempre a subir DJ Sebem cannot tempt Pety to openly declare beef to Buraka Som Sistema.

In summary, the second platform Lisbon is situated between Luanda and the global dancefloors. Elements of both are integrated in kuduro progressivo. What differentiates the Lisbon scene from the other diasporic angolan kuduristas their claim of an «authentic» relation to the source. By emphasizing angolanidade, they try to establish a sustainable and legitimate link to the Luanda scene.

3.3 Platform III – Dancefloors Around the World

Like no other, M.I.A. epitomizes a recent tendency in electronic dance music: Around 2004 DJs such as Sick Girls, Diplo or Daniel Haaksman started to spin a mixture of asymmetric bass heavy beats drawn amongst others from funk carioca, ragga, grime, UK garage and kuduro to create an antipode to the four-to-the-floor and minimal aesthetics that dominate clubland. Newly «discovered» styles like footwork or electronic cumbia are constantly added to these DJ-selections. M.I.A. incorporates elements of these differents genres in her own music and adds controversial rapping.

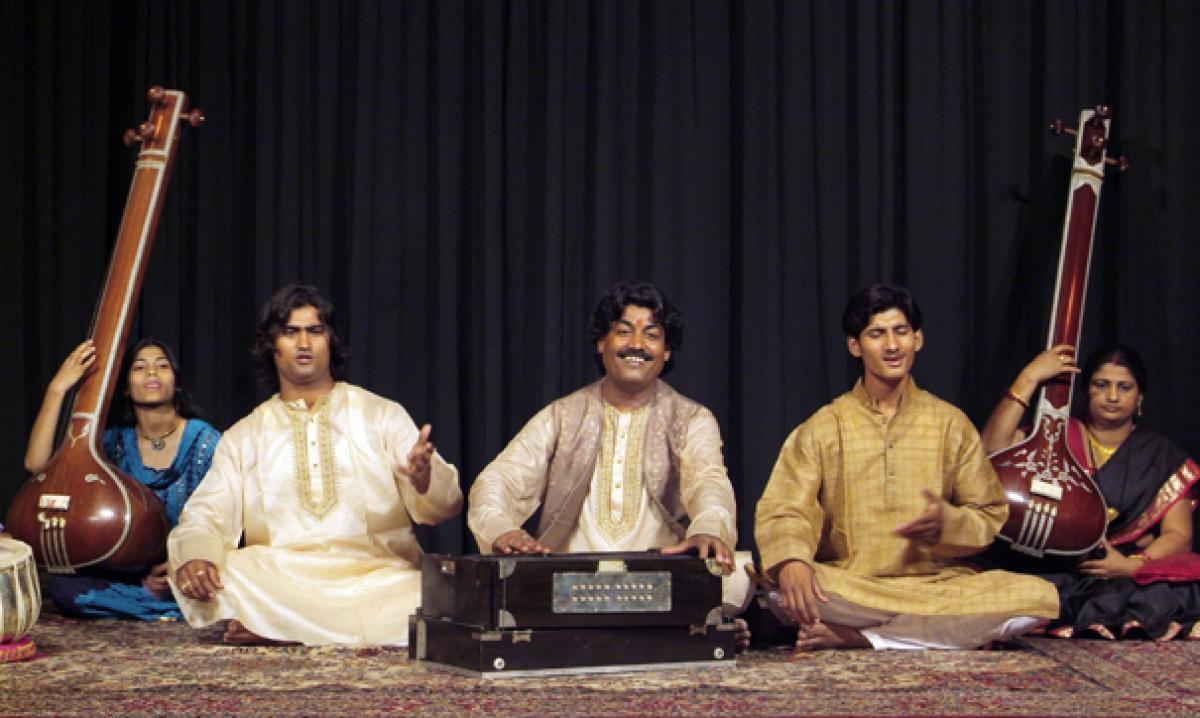

French DJ Frederic Galliano’s has been building a reputation as a connaisseur of African music since the 1990s. In 2006 his Kuduro Sound System compilation introduced kuduro as the electronic angle of African music to this post hip hop club scene. Frederic Galliano travels with a show act called Kuduro Sound System where he functions as DJ/producer and various Angolans raps and dance before him on stage:

Parallel to the trendier club scenes Angolan exile communities around the world listen and dance to kuduro in various settings. The Paris based group Les Princes de Kuduro mention «Les ghettos angolais« (the Angolan ghettos) as their main influence on their MySpace page. As the MySpace profile background we find a depiction of the Angolan flag. In another promotion clip of the group members Manu le Boss is raising the flag, saying «Sempre a bater, sou puro mwangopé … essa bandeira e a minha vida, mon sangre … sou puro, do guetto». See Les Princes de Kuduro dance in front of an Angolan flag in their video Mwangolé (2008) and communicate with words rapped in Portuguese, but written in French:

In this video Les Princes de Kuduro, acting outside Angola, puts an emphasis on the homeland and the local roots. This can be read as a homing desire, a longing for the original homeland. In «Afrikanische Diaspora und Black Atlantic» Hauke Dorsch dicusses concepts of diasporic communities. As a starting point he compares various authors’ list of key constituents of diasporic identity. While some authors during the 1990s insist that the wish or plan to return to the country of origin is vital to a diasporic identity more recent concepts also include a desire to feel at home in the country of residency or any place at all in the meaning of the term homing desire (Dorsch 2000, 29). The overt association with the country of origin also serves an act of solidarity to rehabilitate it in the discourse of the country of residence. While these dynamics can be observed universally it remains fascinating to explore in which particular ways cultural expressions from exiles serve to emphasize a certain relation to the homeland and produce aethetic surplus alongside. Lyrics prasing Les Princes de Kuduro tap into the already strongly developed concept of angolanidade to augment self-esteem of youth in a hostile foreign environment in France.

Conclusions

To sum up, we find that an explicit expression of angolanidade is now especially interesting for musicians outside Angola, whereas in the local scene – first and foremost in the third generation as Sebem calls them – we find a shift towards different topics. The distinction of a «serious» kuduro from its former characteristic as pure animation is on top of the list of the discussions among the musicians and producers. It seems to be very important for the kuduristas to be acknowledged by the Angolan society as serious musicians. Nevertheless, one of their aims is also to bring kuduro to an international audience. To achieve the desired success, kuduristas today seem anxious to develop a distinct individual style and to produce «kuduro mais limpo» («cleaner kuduro»).

After Dog Murras no one in Luanda took over this explicit patriotic style and attitude. It is particularly interesting, that he is not at all mentioned in the recent TV shows Sempre a subir (»always on the rise») and Evolução do kuduro («evolution of kuduro») at the Angolan television, where all other kuduro stars have been given a forum regardless of possible conflicts. While Dog Murras created a specific style in the middle of the first decade of the new millennium he has now somehow vanished from the front page of attention. In Luanda, the Angolan flag seems to have disappeared as a fashion item altogether. At this point in time it seems that the diasporic kuduro artists are the ones who are using patriotic signs overtly.The MySpace profile of Les Princes de Kuduro in France or stage performance of Batida in Portugal are just some examples. But this does not mean that angolanidade has become obsolete in Angola. It is still reflected there through proud exposure of its symbols and icons. However, kuduristas in Luanda don’t seem concerned with showing them off. At the end of the interview with Pai Banana we find that his lyrical content makes the connection when he is rapping about Nzinga Mbandi and Agostinho Neto, two recurring symbols of the mwangolé.

As a continuity of giving life to the concept of angolanidade, kuduro also carries forward a cosmopolitanism, that was a constitutive part of the music scene of the musseques on the eve of independence, as sociologist-novelist Pepetela (1990) and historian Moorman (2008) have shown. Today, this cosmopolitanism is continued in common trans-national identities where kudurista live in Portugal, Angola and Brazil and their work circulates in the lusophone realm. On the more abstract level kuduristas are at home in several worlds at once: While engaging in musical battles in their neighborhoods, they are equally at home in the digital world by transmitting and distributing their output through the online channels of web 2.0.

Kuduro is part of the creation of an imaginary new Angola: economically and culturally potent and promising. In Angola we hardly see any representation of victims but, on the contrary, heroes, both from an insider and outsider perspective. We interpret this celebration of survival and progress in kuduro as a continuity of the power of the musical movements at the eve of independence, described by Moorman: «… music is not immune to the difficult economic and social conditions but by presenting them in new and different terms, music allows people to engage these conditions critically and mockingly and to celebrate their own survival» (Moorman 2008, 193).