«Little-Big» – Chalga-Pop and Metal

The movie Little-Big presents the strange love story between Bulgarian metalhead Boris Red and Chalga-Pop princess Desi Slava, a musician and a singer from two extremes of Bulgarian society. The movie further highlights video clips from a variety of Bulgarian music subcultures.

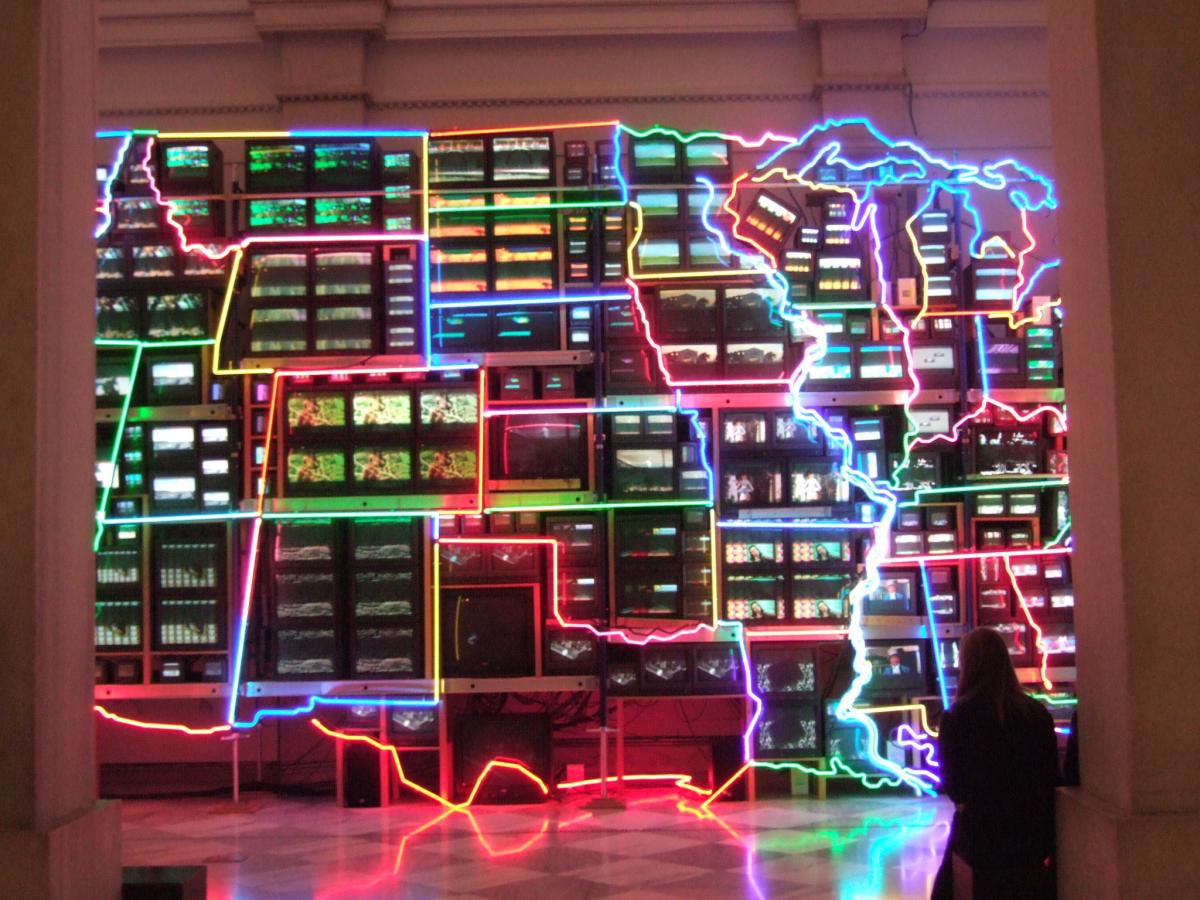

Chalga and metal simultaneously emerged during the 1980s in the margins of Bulgaria’s socialist realist music genres: folklore, estrada (Soviet-style pop and rock) and classical music. The regime designed these three music-styles to propagate its social engineering enterprise. «Modern» music forms, together with long rows of uniform apartment blocks, geometrical boulevards, industrial plants and neighbourhood parks were intended to mediate the evolution of Bulgarian peasants, Roma, Turks and other post-Ottoman ethnic minorities into an «authentic» homogeneous European nation. Metal and chalga signalled the crisis of socialist realist mediation by transgressing its ideological principles. Metal music subverted the «authenticity» component; chalga subverted the homogeneity counterpart.

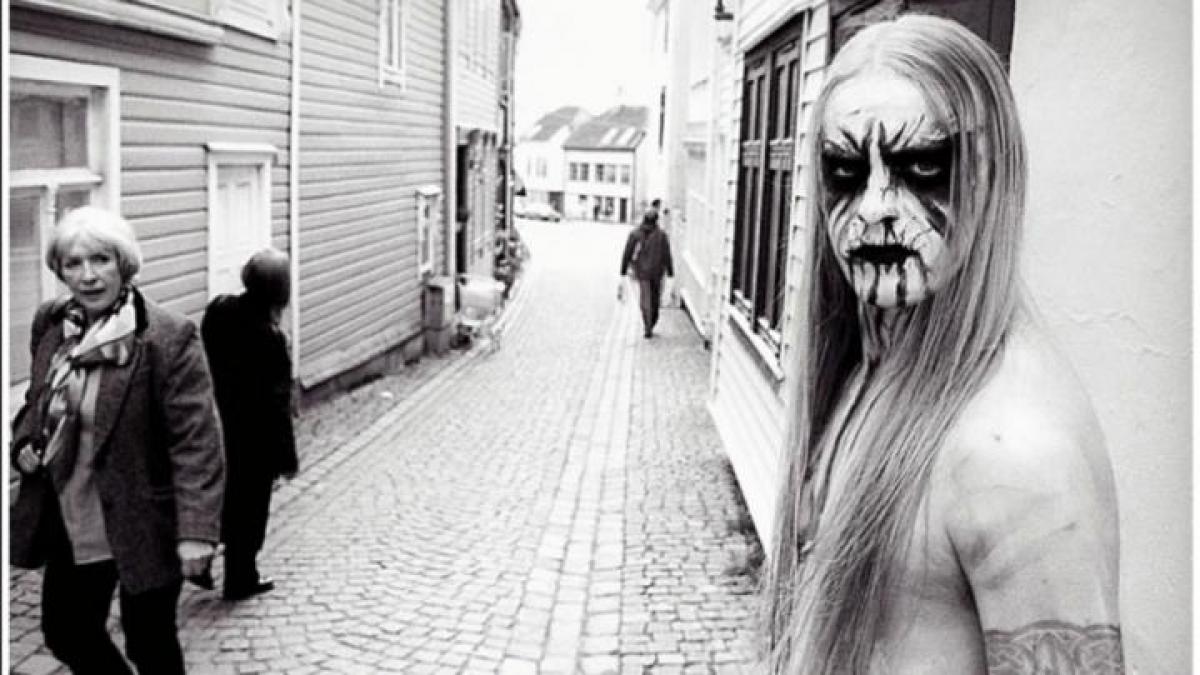

Metalheads – longhaired, tattooed, pierced, dressed all-in-black, infused with cheap beer and different kinds of smoke – performed that indeed socialist Bulgaria built European-style urbanity: a grey, alienating and claustrophobic nightmare, in which nihilism and destruction were the only ways to maintain some sense of personal authenticity. The tragedy of metal was that, despite its oppositional rhetoric, it was fairly safe for the socialist regime. Metalheads subscribed to socialist realist modernism: urban aesthetics, generic homogeneity and stage performance. They disagreed with the regime’s cultural ideology only in regard to modernity’s inner meaning. Socialist realist culture called people to evolve in a futuristic positivist manner. State-employed artists crafted reality as it «ought» to be, according to the Communist Party’s vision of modernization. Metalheads resisted this call by reacting with nihilistic negativism. How did state officials dismantle this resistance? They let metalheads express their nihilism relatively freely thereby turning resistance into playful aesthetics that lacked political impact.

Chalga, on the other hand, was received by the socialist regime as oppositional although rhetorically it had (and still has) nothing to do with politics. Chalgadzhii (Bulgarians who perform or listen to chalga) shattered the vision of national homogeneity by hybridizing oriental-Balkan and western aesthetics, pop and folklore, formal conventions as well as city and village types of sociality. Hybridity means that chalga has rejected the socialist realist message of evolution: building national modernity by adapting local cultural practices to European cultural genres. Chalga deviated from this project by refusing any generic cohesion; it varies from synthetic pop-folk stars like Desislava to small-time Romani bands. Popfolk stars perform global media in the quintessential Balkan tavern (a space for social drinking and eating); Romani bands perform the tavern in global media. However, due to chalga’s deviation from the modernist ideal of homogeneity, neither pop-folk stars nor Romani bands can fuse the two spaces (tavern and global media) together into one local modern space.

More than two decades «after democracy came» (a prominent idiom for the post-1989 era) metal and chalga still mediate marginality. This time, however, their marginality comes in regard to each other. Metalheads tend to despise chalga, because its commercial nature and ethnic «backwardness» prove that capitalism is only another modernist lie. Chalgadzhii, on their part, tend to acknowledge this disdain but claim that they have no problem with metal, because, in principle, they are open to any kind of music. «We, Bulgarians, are hospitable» is a self-ironic idiom, with which both metalheads and chalgadzhii expresses this asymmetry. Why is it self-ironic? Because Bulgarian hospitality keys chalga to a metonym of Bulgarian identity: a quasi-form that is compliant with any kind of cultural domination. Bulgarian metalheads, on the other hand, carry a different aura of marginality. They mimic music imported from Europe and so their marginality is by choice, just like «truly» modern European people.

Can these two musical experiences of Bulgarian marginality communicate with each other constructively? Can Bulgarian metal and chalga generate a shared space of democratic Bulgarian identity? The movie Little-Big suggests that yes, but not as one shared musical form. The film presents scenes in which Bulgarian metalheads and chalgadzhii interact with each other but only in brief encounters, coexistence of hostility, or fantasy. This presentation is self-ironic, because, at the bottom line, the two subcultures perform the same complex of Bulgarian marginality. Metalheads try to be modern by rejecting Bulgarian locality and replicating European counterculture; chalgadzhii by reaffirming that Bulgaria is indeed a marginal hybridity of European modernity.

Videoclips and Fotography from Bulgaria

1. Alternative Trailer (Little-Big): Duet Dvorjak

2. Desi Slava: «Dumi dve»

3. Sisters of Radomir: «Hippies of Pernik» (from Little-Big)

4. Makazchievi Duet

5. Desi Slava: «Moeto Drugo Az»

6. Grupa X: «Zubobol»

Biography

Published on January 11, 2013

Last updated on April 10, 2024

Topics

How does this ideology, but also its sheer physical expressions such as labor affect cultural production? From hip hop’s «bling» culture to critical evaluations of cultural funding.

Can a small chinese radio show about Uyghur music stand against the censorshop of the Communist Party of China? Are art residencies useful?

From Muslim taqwacore to how the rave scene in Athens counters the financial crisis.