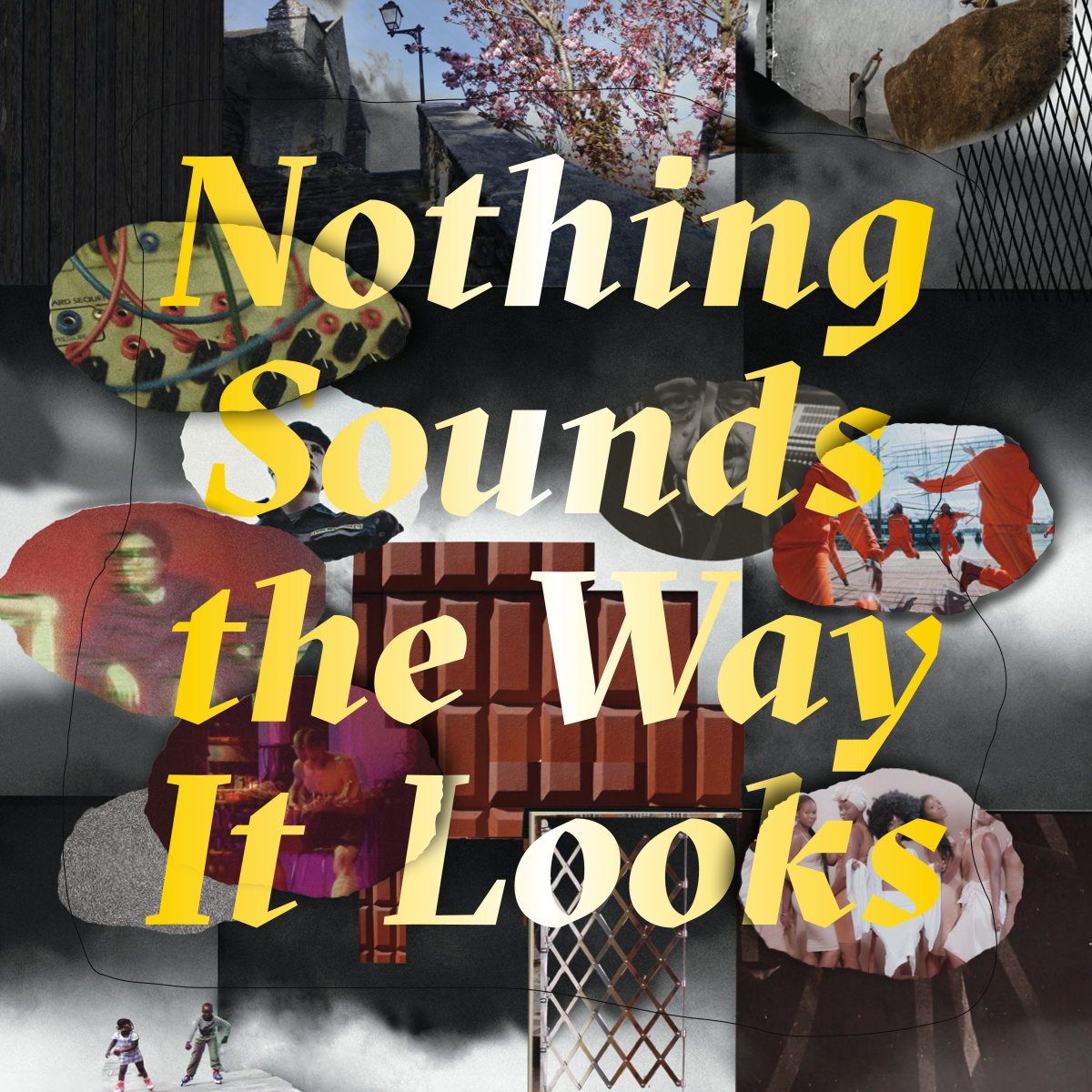

Films can illustrate what it feels like to live in this world. Yet they do not only represent worlds, but also create them – and by that, the subjectivities of the audience. For this new Norient publication, editors Lisa Blanning and Philipp Rhensius commissioned 30 writers from 17 countries to share their thoughts on today’s world through sound and music.

→ Check all articles of this special

→ Download PDF with introduction and table of contents

While the 30 essays offer different perspectives (autofictional, academic i.e.) on different topics (Gender Roles, Sound, Colonialism) they are all connected by one thing: an intense sensory effect, like a «punctum» (Barthes 1981), triggered by one of the 30 films under discussion. Thus, the texts are not so much about as inspired by the films, unraveling narratives about worries, dreams, and hopes in the 21st century that sometimes seem intensified by the current COVID-19 pandemic – from feminist activism in South American club music scenes to critiques of sound and space design as instruments of (colonial) power.

By juxtaposing very different text styles and diverse perspectives, this publication seeks to be a collage, resisting the urge to universalize difference or create false coherence. Like some of the protagonists in the films – such as the Soundcloud rappers in Crestone, who experiment with new ways of collective living – the texts create positive disorientation to arrive at new, unexpected places of thought. At best, this publication connects the unrelated – and separates the supposedly consistent. For this editorial, the texts are loosely divided into eight blocks, drawing from the Norient Topics: Gender Roles, Capitalism, Sound, Colonialism, Spirituality, Protest, Perception, Belonging. In the following, I will briefly outline the essays relating to each topic, in the above order.

Gender Roles

Gender is not naturally given but produced by social and cultural forces. It refers to a social role based on the sex of a person, a mode of power that has been criticized especially by those whose culturally assigned sex and gender do not align, and who are looking for terms and definitions that include, rather than exclude, their individual ways of being. According to the theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, «sexuality extends along so many dimensions that aren't well described in terms of the gender of object-choice at all» (Sedgwick 1990, 35).

In her essay «Intersectionality Rules», the writer and activist Luisa Fernanda Uribe addresses the lack of intersectional thinking in the feminist narratives of South American music scenes. Instead of talking «exclusively about representation or identity», she suggests that «we need to build more radical and collective spaces answering questions about our privileges as agents of the music industry, even if we are women from the Global South».

Some men from the Global North are at the center of critique in writer Agata Pyzik’s essay. The female musicians in Uribe’s text attempt to break free from their gender roles; in Anna Gawlita’s film Krzyżoki, about a traditional Easter ritual in a Polish village, Pyzik finds a desire for «id-pol based on nostalgia for the golden days». While, for her, there are good reasons why «masculinity is being challenged by contemporary culture», she also understands how these men try to regain a sense of manhood.

Blurring the limits of gender and questioning a supposedly authentic way of being is an important part of queer thinking. In his essay inspired by the feature film The Mystery of the Pink Flamingo, the musicologist Adam Harper reflects on how «the queer discovery of the authenticity of the inauthentic (and vice versa) has had an incalculable effect on the aesthetics and semiotics of the contemporary world».

Capitalism

Categorizing has always been a modus operandi of capitalism, a system that tends to subordinate material and immaterial things to profit. In the field of cultural labor, the effects of this ideology often lead to precarity. In her essay «An Ode to Imagination», the writer and musician Noëmie Vermoesen describes how creativity is increasingly threatened by the stress and precariousness which is currently intensified by the forces of the pandemic. Inspired by the protagonist of the film Les Contes Du Cockatoo, who refuses to accept the constant pressure to be productive, she calls for a world in which imagination is freed from measurable expectations.

The musician and ethnomusicologist Suhail Yusuf Khan is anything but unproductive. As a celebrated Sarangi player, he is nevertheless forced to self-market constantly. In his text «Blood Is Thinner Than Money» he claims, without glorifying the past, that this need to find ways of generating income, hasn’t always been the case. The genre in which he operates, North Indian classical music, was once predominantly consumed and financed by the upper class.

The seminal New York record store Other Music was once a somewhat egalitarian place, if not a haven for underdogs. In her essay, the writer Emilie Friedlander, who used to frequently buy records there, mourns its recent closing as «another casualty of the internet».

While the war against algorithms in the music world could be called gentrification of the digital, André Santos sees the decay of the legendary Portuguese music style fado in Lisbon as a result of physical gentrification. In his reflection on these transformational moments in his hometown, he is left with a mix of sadness and nostalgia, but also hope.

A more positive affirmation of place often lies at the heart of club music scenes, although capitalism’s tendency to universalize has paved the way for a widespread commodification of techno and house by white Europeans. In her reflection on Tedra Wilson’s documentary, Dark City Beneath the Beat, writer (and co-editor of this volume) Lisa Blanning shows how Baltimore Club kept its highly localized aesthetics, demonstrating the richness of Black club music in the 21st century.

Sound

Sound is always there even if not recognized. It can expose the world that lies beneath its visibility. However, in a world in which what one sees often seems to be more important than what one hears, it is no surprise that sound still plays a marginalized role in Western society, while sight is privileged as the most valuable source of knowledge – as indicated by many scholars in the field of Sound Studies (e.g. Hirschkind 2012, 63).

This might also be why the sonic layer of films often goes unnoticed, as the journalist Alaka Sahani points out in her essay «Is the Pandemic a Heyday for Unsung Heroes?». Here, she claims that films are very often celebrated for their protagonists, and less for the people who are responsible for the actual audiovisual experience. In her text on the documentary The Sound Man Mangesh Desai, she asks if the COVID-19 pandemic could be an opportunity to rethink the inequalities of star-centrism.

When it comes to countering existing hierarchies of perception, noise has often been the first music genre of choice. In her essay «The Poetry of Noises», the journalist Gisela Swaragita describes how, after having been exposed to harsh sounds in the Indonesian noise music scene, she could transform her disgust of the traffic noises penetrating her flat in Jakarta into an aesthetic listening experience – culminating in her «enjoying the humming of my family’s 29-year-old refrigerator».

Be it machinic or naturalistic, sound in film always affects viewers below the level of consciousness. It is a power that «Hollywood converts into box-office cash», as the writer Dan Barrow depicts it in his essay about Midge Costin’s film Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound. Instead, he argues for a more open approach to film sound-making: a model that entails sonic freedom.

For the sound artist Joseph Kamaru, sound is a similarly powerful tool. He explains in his text «Hearing Is Believing» how, through his work with field recordings, he gained a greater awareness of an environment that is «shared with other living beings». One such insight: «that trees are naturally conductive and can become antennas, capturing radio signals.»

The unheard and overlooked plays a central role in Rayya Badran’s critical analysis of the film Panoptic, in which director Rana Eid narrates her memories of her father, a former general in the Lebanese army. In this essay, the writer unpicks how Eid’s use of sound often contrasts with the images such as the basement of the Beau Rivage Hotel, which was a former torture prison for the Syrian secret service. According to Badran, the audience is invited to learn about the often hidden dark side of Lebanon’s history through listening: a kind of perception that might make one more attuned to the socio-political reality prior to the nationwide protests on October 17, 2019.

Colonialism

The philosopher Sylvia Wynter analyses the multiple facets of colonialism’s legacy through a central narrative. According to her, any struggle concerning race, class, gender or sexual orientation is a facet of the central «ethnoclass Man vs. Human struggle» (Wynter 2003, 260).

An often overlooked aspect in ongoing debates about decolonization is its representation through notions of landscape. In her essay «The Racialized Gaze on Landscapes», the writer and researcher Chandra Frank reflects upon the hailing of the countryside as an idyllic place. As «the countryside has long played an important part in the construction of belonging and nationhood», it has, in the U.K., become «synonymous with white national English identity» that seems to be haunted by colonialism. Frank calls for a reexamination of colonial histories, as with the current efforts to remove colonial statues in South Africa, the U.K. and the USA.

Universalism, as an idea related to colonialism, often sought to subsume the diversity of being and living under a single, Western perspective, often called reason. In her essay inspired by the film Contradict, the scholar Grace Takyi explains that everyday life in Ghana is widely ruled by the Christian religion. For her, the artists portrayed in the film revolt against this religion’s tendency to dominate people’s histories – by writing their own.

Effective acts of decolonization, however, need to be sensitive, especially with questions of representation. In her essay on Felix Blume’s Curupira, Creature of the Woods, the scholar Patricia Jäggi raises questions about the film’s portrayal of Native Amazon communities. She asks: «Is Blume really able to break with the ‹colonial gaze› that defines the white person as an observer and the natives as observed – by having them look back?»

Spirituality

In the context of this colonial heritage, the case of the Utapishi ritual in Kenya seems to show the other sideof the coin. According to the Kenyan artist Kamwangi Njue, the ban of the ritual as a non-religious act of spirituality goes back to the British colonial authorities’ introduction of the «Witchcraft Act» in 1925. Cynically, in the ongoing process of the marginalization of this ritual – a kind of mental purification by a specially trained healer, embodied by Jackson Matiere in the speculative short film Tapi! – the role of money creeps in again. After a court hearing with the county pastor, Matiere is no longer allowed to officially practice his ritual – but is still allowed to do the associated dance, as it benefits tourism.

Similarly, invisible forces are floating around in the experimental essay by writer and director Azin Feizabadi, who assesses the myth and legacy of one of Iran’s most beloved singer/songwriters, Ebrahim Monsefi. Monsefi, Feizabadi writes, «cannot be described in one sentence, one film, or one book. He might breeze into you or not. If he does, you’ll feel it – you’ll understand his pain and sorrow, humor, lovesickness, or strangeness.»

Protest

Sorrow and pain have always been important drivers for protest, be it politically explicit or implicit in the personal or private realm. The latter form is expressed by the musicians in the film Her Bijî Granî. As players of the energetic Kurdish wedding music style granî, they could be seen as part of protest culture. In his essay, the scholar Martin Stokes dissects the significant political meanings in songs about love that are usually seen as apolitical.

Very explicit, by contrast, is the effort of musicians facing the aftermath of the Islamist invasion of Northern Mali in 2012, during which music was widely banned. In his text about the film It Must Make Peace, journalist Simon Broughton describes their musical practice as a search for peace and freedom.

While these musicians are fighting for freedom in the literal sense, Alex Freiheit's struggle is more subtle, embodied in gestures that are exemplified in RRRKRTA’s essay «Static Resistance». In the film SIKSA: Stabat Mater Dolorosa, Freiheit, frontwoman of the Polish band SIKSA, addresses political categories such as family, church, and state through childhood memories of socially accepted violence, in a way that is not confrontational, but intimate.

Perception

To think, to listen, to see, to be in the world is always a matter of the body. One cannot separate oneself from one’s perception of the world. According to the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, «we must not, therefore, wonder whether we really perceive a world, we must instead say: the world is what we perceive» (Merleau-Ponty 1958, 18). Perceiving another body through close proximity, intimacy, is a mode of being that has undergone a radical change since the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing. Since then, it seems, intimacy has been happening mostly online, transforming its conditions from those of trust into those of isolation.

In her reflection on the docu-fiction Crestone, in which a group of SoundCloud rappers oscillate between their isolated online selves and the search for new meaning in life, the curator Daniela Seitz proclaims the need to «look beyond the apparent narcissism of online culture, and the blurred line between the virtual and real.» She reminds us that «it is more important than ever to unlearn established modes of online behavior, and reflect on how the internet echoes existing systems of oppression.»

The idea of showing weakness as a strategy to counter the frictionless online self resonates with Florence Jimenez Otto’s critical reflection on perfectionism. According to Otto, a creative coach who has worked in the music industry for years, perfectionism can be a real threat to mental and physical health. To overcome the faulty logic of self-judgment, she calls for a different perception of the self: a personality that is soft and permeable, «and less narrow-minded and rigid».

Enriching the world with different forms of being and doing is at the core of the essay by writer (and Norient editor) Philipp Rhensius. In describing Eden Tinto Collins’ short film about the artist Amanda Baggs, a genderless nonverbal person with autism, Rhensius claims that communication goes far beyond the verbal. According to him, «silencing other people’s communication is an attempt to defend a world that is prefabricated and based on representation, against one that is in a constant state of becoming.»

Similarly fragmented is the structure of the film Dazzle Lights. According to the writer Lola Baraldi, the viewer is confronted here with a radical blurring of images and thoughts. As the experimental shamanic cumbia band Los Síquicos Litoraleños calls «for alternative ways to illustrate their antics, the documentary finds ways to adapt and innovate by blurring the separation between form and content, allowing a more authentic world-building that reflects surrealism, fascination, and confusion.»

Camille Degeye’s Journey Through a Body likewise seems to mirror the creative methods of the musician it portrays. The film’s contrasting of the romantic with the banal leads writer and artist Steph Kretowicz to ask in which ways the protagonist’s daily routines are harnessed by the messiness of his «creation and the diverse technological ecology it draws from.»

Belonging

People are not just attached to their family or the nations they live or were born in, but to things, feelings, sounds, and like-minded people across the globe. Yet the pandemic has laid bare how capitalist hyper-individualism has led to a crisis of collectivity, and therefore of a sense of belonging.

Ferry Heijne, frontman of Dutch band De Kift, attempts to overcome this crisis by writing new songs. According to the writer Angus Finlayson (who also copy-edited this collection), «he seeks out moments of human connection; confronted with individualized suffering, he offers comforting universals.»

Less universal and more particular is the search for belonging in the film Don’t Rush, a portrayal of two young men with a passion for rebetiko, the Greek urban folk music made by refugees. Musing on what is now viewed as a rich cultural tradition started by outcasts and illegals with a penchant for hashish, the writer Clive Bell teases out a telling lesson for an ongoing humanitarian crisis.

To belong often means to be able to communicate. In his essay inspired by the film In Your Eyes, I See My Country, in which two Israeli musicians travel to Morocco, the scholar Keith Kahn-Harris observes that lacking a common language is not always an obstacle to communication but «can offer its own insights.» It can help to build new connections without preconceptions.

History is not just about what happened but also what might have happened. It might only take a newperspective to change a biography. Aysel Özdilek reflects on this fact – that any unfolding plot might be an invitation to consider other outcomes – in her essay about the Turkish composer İlhan Mimaroğlu. After watching the film Mimaroğlu: Robinson of Manhattan Island, the writer reads his life as a «waiting room of possibilities, where the past, becoming virtual, continues to have an impact on our current situation.»