Challenging Orientalism Pt. 1

Six international curators from the Norient community have researched contemporary music videos that re-imagine, parody, or deconstruct Orientalism. The final selection is presented in the virtual exhibition «DisOrient: Welcome to the Hall of Mirrors», which is part of the German festival Mannheimer Sommer. Here is the shortlist by the curator and researcher Berit Schuck, who focuses on videos from Morocco, Egypt, and Lebanon.

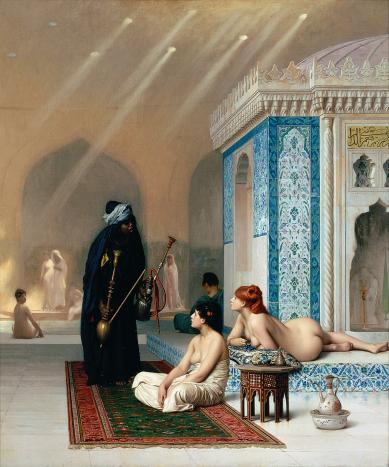

Since the Age of Enlightenment, the relations between the Orient and Occident have been shaped by that which the Palestinian researcher Edward Saïd calls «Orientalism», a set of beliefs and stereotypical narratives to which belongs the idea that Oriental culture is unbound by reason, cruel, and simultaneously disempowering and sexualizing women. Now, these narratives have not only impregnated how Oriental cultures are presented outside of their context until today, they have also affected how they see themselves. Since the liberation movements of the 1960s, however, a growing number of contemporary artists and thinkers have participated in a critical reflection of imperialist or Orientalist stereotypes, developed counter-narratives, or opened themselves up to completely new ones, eventually creating artworks about home and history, desire and estrangement, isolation and exile from dis-Orientalist perspectives.

The following seven tracks and videos, all produced between 2016 and 2020, are examples of this shift. They explore, criticize, and re-imagine a variety of the most popular Orientalist narratives: the idea of the subaltern who needs guidance from someone outside his or her context to achieve a goal; the idea of the cruel, unimaginable rich pasha who under threat of his life transforms into an insightful politician; the stereotype of the veiled, dark-eyed woman and the particular places she inhabits for the pleasure of men.

Created by media artists, composers, and musicians in Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, and the Netherlands, the eight works offer a variety of perspectives and contexts for encountering how Orientalism still manifests in ways that too often go ignored and unquestioned, and how this can be exposed, criticized, and re-framed.

Music: Marwan Pablo

Video: Kareem Ali

Track: Free (Egypt, 2020)

«Free» is a good example of the kind of music the Alexandrian songwriter and rapper Pablo Marwan, «Egypt’s godfather of trap» (Vice Asia 2019), has been producing in different constellations over the past few years; the song produced by Molotoff features hard-hitting, trip-inducing hip hop beats, minimal electronic music, melancholic melodies, and always poetically performative, yet sometimes erratic lyrics. Compared to Arab folklore and international pop, trap reaches a relatively small segment of the Egyptian public. Moreover, Egyptian trap does not succeed yet in addressing big international audiences, unlike electro sha’abi or California-style rap. Thus, «Free» was written from the margins and for the margins, despite its immediate success, reaching No. 1 on Egyptian YouTube upon release. Moreover, the song discusses and reflects on marginal practices from a Dis-Orientalist perspective.

For example, the refrain of the song may be a complaint, but listening to the lyrics and Marwan’s performance makes clear this complaint is not addressed to those in the center. It’s a call for self-liberation. Using free verse and accelerating the speed of the performance, showing off his skills, the singer is basically telling his followers: «When you are losing it, you are free». Also, the video created by Kareem Ali supports this strategy to be free, which we can call «fugitive planning» (Harney and Moten 2013). Divided into three sequences and preceded by an intro announcing the title, the video considers Orientalist stereotypes such as the idea that talented people in the South would (want to) copy music productions from the U.S. and seek access to the global culture industry (that encourages reproductions rather than experimentation) to negate these stereotypes. All of the sudden, inhabiting the margins of hegemonic discourse is a possible way to be free.

The opening shot shows the singer roaming around the wall that separates Alexandria from the sea, and Egypt from Europe, and while this image seems to say he is trapped, his free movements betray the first impression, underlined by the graffiti behind him that simply says «free», quoting the title of the song. What follows are images of the singer and his crew sitting on the top of a Mercedes Benz or leaning out of its windows while driving across the city and down Alexandria’s sea road. However, the singer doesn’t seem to need the fancy car for more than the film shoot. The more images you see, the more the car appears like a vehicle that anyone can pick up anywhere to have some fun, and not as a status symbol. The last sequence of the video finally shows Marwan on a horse and in a villa surrounded by artifacts from Alexandria’s golden era, including Art Deco furniture and Modern Art paintings, such as Picassos’s Blue Period portrait of an absinth drinker. Again, instead of celebrating this moment that speaks to intellectual wealth and white privileges, Marwan leaves us with the impression that all of this is not that desirable. The images look dim and foggy, the scene outdated. Losing it and becoming free is all you could ever want.

Music: Wegz

Video: Hatem Tag (Director), Ahmed Thabet (DOP)

Track: Dorak Gai (Egypt 2020)

«Dorak Gai» written and performed by Wegz, another young rapper from Alexandria, engages with a different music genre, but attempts something similar with regards to Orientalist stereotypes. Again a Molotoff production and one of the most popular songs that came out of Egypt in 2020, «Dorak Gai» is an Egyptian rap song combining hip hop beats with experimental electronic music and sha’abi elements. The lyrics, however, straightforwardly dismiss Orientalist tendencies within the rap scene, such as the appropriation of underground rap and exploitation of poor people in commercial productions.

Moreover, what at first seems to be a critical comment on the success of California-style gangsta-rap in Egypt, soon appears to be a disguise for a vitriolic critique of the Egyptian state and its dependency on Western allies. The video introduces Wegz planted in the middle of a garage in a poor Egyptian neighborhood, surrounded by followers wearing gas masks, which is a direct comment on the failure of the Egyptian government to stop the spread of the Coronavirus in these neighborhoods. Next you see Wegz standing in the middle of a crowd dancing and cheering to the music while facing a Coronavirus task force that has blocked the street. Wegz may be talking about a fight with another rapper, we understand, but what we see is not only this fight, but a grotesque, comic representation of the ineffective measures taken by the Egyptian government to fight the pandemic.

Music: ISSAM

Video: Issam Harris (Director), Essadik Asli (DOP)

Track: Trap Beldi (Morocco, 2018)

Two recent tracks and videos by the Moroccan rapper and composer ISSAM offer new perspectives and contexts for encountering the ways in which Orientalism often goes hidden. According to the online music magazine Scene Noise:

Inarguably, one of the best rap tracks to come out of Morocco in 2018 was ISSAM’s «Trap Beldi». Released on November 19th, the song went viral not only because of how catchy it is both lyrically and musically, but in part due to its visually stunning video which currently holds over nine million views on YouTube. The Adam K produced beat (...) complimented ISSAM’s witty, self-assertive lyrics and it all tied in with the videos vintage inspired theme, which didn’t stray far from home with the rapper and his clique sporting retro Moroccan, Tunisian and Algerian football jerseys, and loitering around town on Motobécanes in colorful tracksuits. (Adel 2019)

The review gives a full account of what you can hear and see in the video, however, the «vintage inspired theme» must be read both ways: The football jerseys and colorful tracksuits may trigger memories and a sense of nostalgia for all who have visited or live in Morocco. They are a distinct part of popular Moroccan culture. One should nevertheless keep in mind that they are also a trace of French colonization, and when ISSAM uses them in a music video that talks about the struggle of Moroccan youths for independence, it is equally possible to see them as part of this struggle.

Music: ISSAM

Video: Issam Harris (Director), Essadik Asli / Mohcine Aoki (DOP)

Track: Makinch Zhar (Morocco, 2019)

«‹Makinch Zhar› capitalizes on the same formulae that made Trap Beldi a smashing success», says Scene Noise (Adel 2019), but the track focuses more on the struggle of Moroccan artists and culture workers, both at home and in the world. «Makinsh zhar» in Darja literally translates to «there’s no luck». The lyrics of the song exemplify what this means for artists in the post-colonial Moroccan context. They tell us a Moroccan artist would have to wear nice watches and clothes from abroad and pursue an international career in order to be recognized at home. Meanwhile, the symbolic use of eyes in the video reflects on Moroccan culture’s superstition of trying to achieve something while people watch closely.

A Moroccan artist thus faces a dilemma. He can describe the effects of Orientalism on the people or on himself, just like Frantz Fanon did in Black Skin, White Masks (Fanon 1967 [1952]), or keep searching for his own new path. But whatever he does, he will always experience desire and estrangement, he will never be free to just be himself. I disagree with the critic of Scene Noise who writes, «ISSAM’s female companion in the video is also a metaphor for his own moral compass that’s ever present in the midst of everything» (Adel 2019). I would rather say the female companion suggests a feminist positioning of the artist and opens up to a new narrative. ISSAM’S invitation to Artsi Ifrach / Artsimous to design the costumes for the video for sure is an indication that a different life, a different community where you have moved beyond Western living and working styles, seems possible.

Artist: Mashrou Leila

Video: Jessy Moussalem

Track: Roman (Lebanon, 2017)

In my research, I found three more tracks and videos that discuss and reflect on how Orientalist stereotypes affect our lives until now. The first one is «Roman» by the Lebanese indie rock band Mashrou’ Leila, which delivers musically what the band is best at: warm beats and falsetto harmonies that meet the tenor of lead singer Hamed Sinno, while dismantling Orientalist stereotypes of the Arab woman. The music critic Anastasia Tsioulcas, following a Tiny Desk Concert with the band in New York and a few months before their Cairo concert, described the song as follows (her review says it all):

Working with an emerging female director from Lebanon named Jessy Moussallem, the all-male members of the band (singer and lyricist Hamed Sinno, violinist Haig Papazian, keyboardist and guitarist Firas Abou Fakher, bassist Ibrahim Badr on bass and Carl Gerges on drums) take a back seat – quite literally – to a group of women. With dark-hued beats and gorgeous falsetto harmonies haloing Sinno’s ardent tenor, this song will be a welcome find for casual listeners. But as ever with Mashrou’ Leila, there’s a lot of subtlety in both the text and the visuals to «Roman» that challenges stereotypes – from all corners. As the band explains, the women in the video are «styled to over-articulate their ethnic background, in a manner more typically employed by Western media to victimize them.» (Tsioulcas 2017)

Watching the video, you cannot ignore the complexities of the female representations. The women are dressed in an array of figure-hiding Middle Eastern clothing like caftans and abayas, and with many wearing various kinds of veils, from headscarves to the face-covering niqab – these are especially stereotypical outfits, given Lebanon’s diversity and what women there actually wear. At the same time, these outfits do not cover the differences among the women. They appear young and old, tall and short, standing still and passionately dancing. Only the last shot pushed the differences aside insofar as the Western perspective takes over. In the last shot, seen from the bird’s eye perspective, the women all look the same.

While Sinno’s lyrics tend towards the elliptical, the song’s title might also be playing with the idea of cultural divides: «Rum» is the classical Arab word for Romans, or Byzantines, i.e., non-Muslims, and later became associated with Christians and Europeans more broadly. The thrust of the video, however, is one word from the song’s refrain: «Aleihum!» (charge). It’s a cry for self-realization, as Mashrou’ Leila explains: a way of «treating oppression not as a source of victimhood, but as the fertile ground from which resistance can be weaponized» (Tsioulcas 2017).

Artist: Sevdalizah

Video: Emmanuel Adjei

Track: Human (Netherlands, 2016)

The second song from this region that I found interesting for the context of the exhibition is «Human» by the Iranian-Dutch singer, songwriter, and music producer Sevdalizah. I would describe this song as a powerful critique of sexualized representations of Oriental women. The work talks about how it feels to be watched, from the perspective of a woman in an overtly (white) male environment. With its super-slow, dark-hued beats and the warm voice of Sevdalizah, the song seems at first an easy listening experience, but as in other works by Sevdalizah, the lyrics and the video represent a stark contrast to the music.

You see the singer entering a Renaissance mansion led by a black servant, undressing herself under the eyes of a range of white old men, then mutating from a human into a creature between woman and goat and performing almost naked in the middle of a corral. You hear her speaking slowly a sequence of words that is repeated until the video stops and which sounds like a prayer: «I am flesh, bones; I am skin, soul; I am human.» In short, as soon as you open your eyes, «Human» reminds you of the struggles female musicians face when entering dominantly white male environments, such as the music industry, from the perspective of a non-western woman. The lyrics meanwhile tell you what some of us do in such situations.

Artist: Joe Namy, scored by Lafawndah with Alya Al-Sultani

Track: Libretto-o-o: d’artifice (2020)

Video: Joe Nam

Last but not least, I was fascinated by the work «Libretto-o-o: d’artifice» that the Lebanese-American media artist, composer, and educator Joe Namy developed as part of his ongoing research on the history and resonance of Middle Eastern opera. The work, which first took the shape of a cine-performance (Namy, Lafawndah and Al-Sultani 2020) and now is a one-channel video with soundtrack, raises questions about the poetics of the opera house, opera music, and the relations between opera as form and nation-building processes. «Traversing the architecture of five theaters throughout the Middle East (...) the film is a meditation on the poetics of the opera house, stylistically embodied as a remake of Kenneth Anger’s Eaux-d’Artifice» (ibid.). The sonically rich soundtrack explores the relations between musicians and opera houses in Algiers, Beirut, Cairo, Marrakech, Rabat, and Muscat and how these inform the role of opera in these places. (Read the author’s interview with Joe Namy here).

List of References

This playlist has been compiled in the context of «DisOrient: Welcome to the Hall of Mirrors». A virtual music video exhibition by Norient for Mannheimer Sommer (July 12–22, 2020). Because of the Corona pandemic, the festival took place as a virtual event.

Biography

Links

Published on June 23, 2020

Last updated on May 18, 2021

Topics

Does one really need the other in order to understand oneself?

Why is a female Black Brazilian MC from a favela frightening the middle class? Is the reggaeton dance «perreo» misogynist or a symbol of female empowerment?

Watch how cutting-edge music from Brazil to Singapore is represented in moving images.

How did the internet change the power dynamic in global music? How does Egyptian hip hop attempt to articulate truth to power?

About fees, selling records, and public funding: How musicians strive for a living in the digital era.

From Beyoncés colonial stagings in mainstream pop to the ethical problems of Western people «documenting» non-Western cultures.

Snap