The New Hi-Tech Underground

In the past decade, culture was longing for the nostalgic and authentic. The new Internet underground celebrates the contrary: hi-tech, artificiality and kitsch. Is it a critique of capitalism or a capitulation to it? Both and neither, says Adam Harper, the philosophical flight attendant of Internet music trends such as bubblegum-bass and vaporwave. From the Norient book Seismographic Sounds (see and order here).

Music that resists the mainstream, or what is sometimes called «countercultural» music, has often been associated with humanity, warmth and the past, in contrast to industrial technologies: its opponent. This music includes popular genres like folk, punk and indie, and typically aims to escape commercial and inauthentic musical intentions through use of older, «retro» styles, techniques and technologies. But that’s changing: a new movement within underground music is reversing that strategy, and in 2015 that means exploring hi-tech digital technology and its consequences.

A key difference between old and new technologies is that of surface. Traditionally, the preferred surface sound of countercultural music is «rough», as in the amateur, cracking voice of the folk singer, the sloppiness of indie rock technique, or the hissing, grainy qualities of analogue media. This aesthetic preference, still prevalent today, is known as «lo-fi», (referring to sound quality, being the opposite of «hi-fi»). Associated with amateur or «DIY» music-making, it stood in opposition to a mainstream deemed slick, artificial, inauthentic, and tainted by modernity. The new digital movement, however, represents the «other» of lo-fi – not merely hi-fi, but hi-tech, as it encompasses a range of multimedia strategies beyond sound quality. Hi-tech is lo-fi going on the offensive, engaging ambivalently with those same qualities it had previously rejected. For many, the Internet embodies these hi-fi qualities.

Stylistic Pluralism, Kitsch and Non-Humanity

So what does the Internet sound like? Well, ultimately, no one thing in particular. But the characteristics that the Internet and the wider digital world are perceived to have found their way into music in three main senses: stylistic pluralism, kitsch and non-humanity. These three areas are never entirely separable from each other, but some releases lean more one way than others. A good example of a release that combines all three is Blank Banshee’s album Blank Banshee 1, which presents a kaleidoscope of candy-colored textures and artificial voices while spreading itself through various forms of hip hop and dance musics (see interview with Blank Banshee here).

First, the Internet provides the contemporary listener and music-maker with opportunities to explore the pluralism and juxtaposition of musical styles. Not only do genres combine vigorously and complexly in both mixes and new music, but a «collage» style of production has been founded on disorienting and yet oddly serendipitous combinations of samples and hi-tech sound effects in the music of Elysia Crampton, Chino Amobi, Total Freedom and DJWWWW. Their work achieves moments of sublime beauty and samples from R&B or classical music. These sounds are starkly contrasted with violent rhythms that suggest factories of the future, and seem to portray the modern human made God-like by technology.

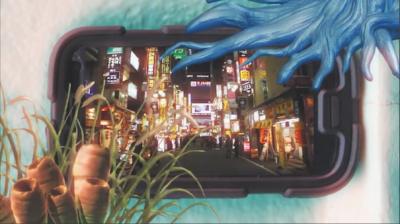

Second, the digital world’s supposedly superficial qualities emerge with a new interest in kitsch and cuteness. The new genre of vaporwave samples late 20th century muzak and slows it down, thus highlighting its dream-like and anaesthetic qualities, which connects it to the technocratic and corporate spaces of late capitalism (see article on vaporwave here). Artists like YEN TECH and Gatekeeper make highly skilled pastiches of almost aggressively developed electronica. New labels such as PC Music and Activia Benz explore high-pitched and childlike excitement surrounding romantic love with considerable intensity, straddling the border between pop and satirical excess. Throughout the online underground there is a keen interest in an imagined Japan, not only as a source of hi-tech mythologies (Japanese characters in artist names and titles are a hallmark of vaporwave) but as the home of Kawaii and the alluring sentimentality of anime.

Third, there is a curiously robotic, coldly inhuman or post-human quality to much hi-tech music. «Humanity», of course, is ultimately a construction that, in popular music, is based around imperfection, acoustic instruments, emotion and analogue «warmth». Instead, much hi-tech enters the «uncanny valley», the zone where something is all the more disquieting for its almost-but-not-quite resemblance to human attributes. Disembodied and reprogrammed samples of the human voice are common, as are samples of it pitch-shifted with MIDI and played like so many keys on a keyboard. Often, as in the work of Giant Claw, Karmelloz, DYNOOO or RAP/RAP/RAP, we encounter approximations of human music, as if algorithms or artificial intelligence had sorted through the various elements of 21st century culture and arranged them according to their own mysterious logics – as indeed many parts of the Internet actually do.

Digital Sources and Shiny Surfaces

Many musical acts exploring the hi-tech aesthetic, such as James Ferraro, Oneohtrix Point Never or Gatekeeper, started out in more retro and/or lo-fi idioms. Today, the lo-fi / hi-tech opposition makes a comfortable (if not comprehensive) parallel with that of analogue and digital technologies. But «digital» has come to mean so much more than a certain way of electronically coding information – it has come to refer to the speed, information-richness and virtual spaces of modern technological mediation, embodied most famously (but not exclusively) by the Internet.

Much of this new hi-tech music is disseminated on the Internet, not just out of ease but often because the labels and musicians behind it have an active dislike of retro media. This has sometimes meant that underground music discourse has been slow to cover it, heightening the divide. It’s important to note, however, that not all music released over the Internet necessarily explores or aestheticizes its digital origin. The main sites on which it’s released – Bandcamp, SoundCloud, YouTube, MediaFire – show a full complement of musical styles and aesthetics, and ought to be taken seriously as an arena for any kind of music. But with hi-tech, these digital origins, as a channel of cultural communication, become somewhat self-aware, much as the lo-fi underground did in the 1970s-1990s when it came to associate relatively poorer technology (such as cassette and cheap instruments) with the music it carried.

It is not just the digital world that hi-tech scrutinizes in its zip files and YouTube videos, but the whole edifice of twenty-first century technocracy, animated as it is by the imperatives and colonization of neoliberal capitalism. The technological surface of the digital is its skin and its sensorium. Much hi-tech music can perhaps be considered the aesthetic equivalent of «accelerationism», a political philosophy that holds that the best course of action is to push capitalism forward into its own dissolution rather than to abscond from it. In any case, far more than retro or lo-fi can today, hi-tech music engages with modernity, imagining where we are, where we’re going and how deep it gets.

This text was published first in the second Norient book «Seismographic Sounds».

Biography

Shop

Published on January 15, 2016

Last updated on April 10, 2024

Topics

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

How does this ideology, but also its sheer physical expressions such as labor affect cultural production? From hip hop’s «bling» culture to critical evaluations of cultural funding.

How does the artits’ relationship to the gear affect music? How to make the climate change audible?

Snap