During the revolution in January and February 2011, most Egyptian pop singers said nothing. A few month later they are back, praising the national martyrs in song. A PR gaffe or more?

One of the pop-culture phenomena coming out of the 2011 Egyptian revolution is the emergence of a subgenre of popular music videos dedicated the memory of the people killed during the eighteen days of protesting that brought down Hosni Mubarak’s government. This is a notable change of pace from the mass-media Arabic-language music industry’s usual stock in trade, schmaltzy songs of chaste romance, for several reasons. First, songs that aired as music video clips via satellite channels in Egypt during the Mubarak era were generally devoid of domestic politics, except for nationalist pablum that either avoided politics entirely or portrayed Mubarak as the legitimate leader of his people. Second, the visual imagery was usually carefully storyboarded and filmed: pretty people in pretty places is the norm in the world of Arabic video clips.

The video clips that memorialize the martyrs differ on both counts, in that simply referring to the revolution in mass media is itself a political act, albeit not necessarily a very clear one. And, in sharp contrast to the elaborate, soap opera-like mise en scène that dominates the field, the «martyr pop» videos tend to eschew studio visuals in favor of news footage. Above all, there is a powerful emphasis on photographs of the martyrs. (For those unfamiliar with the Arabic usage, the term «martyr» (shahid in Arabic) is often used in a secular context to denote people considered to have died in the name of a national cause.) However, despite the inherently political nature of singing about the revolution, most of the singers actually appear to seek a middle path in which their political sympathies are not truly disclosed.

There is much to analyze in these video clips; for present purposes, I will confine my remarks to some of the more striking aspects of the visual and sonic imagery employed.

The first martyr pop video clip, as far as I know, is «The martyrs of 25 January», by the singer Hamada Helal. Released within a day or two of Mubarak’s ouster, this song is by far the clearest of the bunch in its singer’s politics. A great deal of the news footage that made its way into this video clip plainly includes photos and videos of (often very angry) protesters calling for Mubarak and his government to leave power. The news footage is intercut with footage of Helal himself walking around the environs of Tahrir Square and participating in various ways with the protests: posing with other protesters for photographs, praying with them, and generally interacting with the scene. It’s difficult to guess exactly when the footage was shot, but since the video clip appeared so quickly after Mubarak left power, it is reasonable to estimate that the footage of Helal was shot over the course of several days in between the time when the numbers of the dead and their photographs were released, and 11 February, the day Mubarak stepped down. Much of the video is also dedicated to showcasing a lachrymose Helal literally weeping about the martyrs, which is more in keeping with scripted studio-produced visuals than with the aesthetic that other martyr pop videos seem to pursue.

Another early martyr pop video clip is a duet between the singers Ramy Gamal and Aziz al-Shaf‘i, «I love you, my country». Al-Shaf‘i elaborated the words and melody from a song by the old composer Baligh Hamdi that memorialized people killed during the 1967 War. The tune accordingly echoes an older style of nationalist song, rather than Hamada Helal’s distinctly contemporary style, which sounds more (on a musical level) like a song of unrequited love.

There are occasional quotations of news footage, particularly those that showed people being shot down in the streets, but the bulk of the visual imagery is photographs of the young protesters who were killed. Most of the photos bear no indication of mourning, such as a black stripe near the left-hand corner, but a number of the faces of the dead have become well known, thanks to wide dissemination of the photos in Egyptian national media. (E.g., Ahmed Basyoni, the curly-haired gentleman in glasses, and Sally Zahran, the only female martyr depicted in this video.) On a subtly more political level, the first martyr’s photograph shown is not from the revolution at all, but the famous photograph of Khaled Said, a young man beaten to death by police six months before in the Sidi Gaber district of Alexandria; the popular outrage over the murder of an innocent person by some apparently corrupt and brutal police officers was a contributing factor to the sense of injustice that motivated people to attend the first protests of the revolution, on 25 January — Police Day, in Egypt.

Hany Shaker’s song, «The voice of the martyr», has some of the most referential lyrics of any of the songs in this group, specifically discussing the fact that people protested for freedom and against corruption by demonstrating in Tahrir Square. Interestingly, the production credits take care to name «the Palestinian poet» Ramy Yusef as the author of the lyrics. (The majority of lyricists in the Arab pop music industry are Egyptian.) Like Hamada Helal’s video (and unlike «I love you, my country»), the video clip includes unambiguous footage of people calling for Mubarak to step down, as well as a considerable amount of the violence perpetrated by the security forces. Hany Shaker, who composed the melody himself, is one of the oldest singers still popular with young people – he’s nearly sixty now – and is known partly for being one of the last musicians trained by the old masters of the previous generation. Unsurprisingly, then, he chose to write a relatively old-fashioned nationalist melody, which would sound more recognizably like a military march or dirge without the electronica in the arrangement.

Amr Diab, perhaps the biggest star in the Egyptian musical universe, incurred some bad press during the early days of the revolution: not only did he make no comment at all about his political views, but he gathered his family on his private jet and flew them to London to wait out the uprising and see how things developed. Egyptians were especially irked that the wealth that they have given him over the years was spent on the means to escape Egypt altogether, with no apparent loyalty or sense of obligation to stay and, if not participate, at least lend his voice to whatever he believed in.

It’s probably not a coincidence, then, that Amr Diab has now released an extraordinarily somber martyr pop video clip — indeed, it is hardly recognizable as a video clip in the usual sense, in that there is no living being shown at all. The whole of the video, entitled «Egypt said», is a series of photographs of some of the martyrs, edited together with a heavy, dolorous melody that would sound pretty depressing, if not for Diab’s beautiful voice. Of special note are two editing choices regarding the photographs. First, the only woman depicted is muhaggaba (one who wore a veil), although a number of other women died, some of whom – like the now-famous Sally Zahran, mentioned above – did not veil. Second, the mourning photographs include several police officers, who presumably were not shot or bludgeoned to death as protesters, but who died when angry mobs of protesters across Egypt burned down their local police stations. Given the still-simmering rage directed towards the Egyptian police and security forces – notoriously corrupt at every level – as a root-and-branch element of Mubarak’s dictatorship, this is a surprising choice.

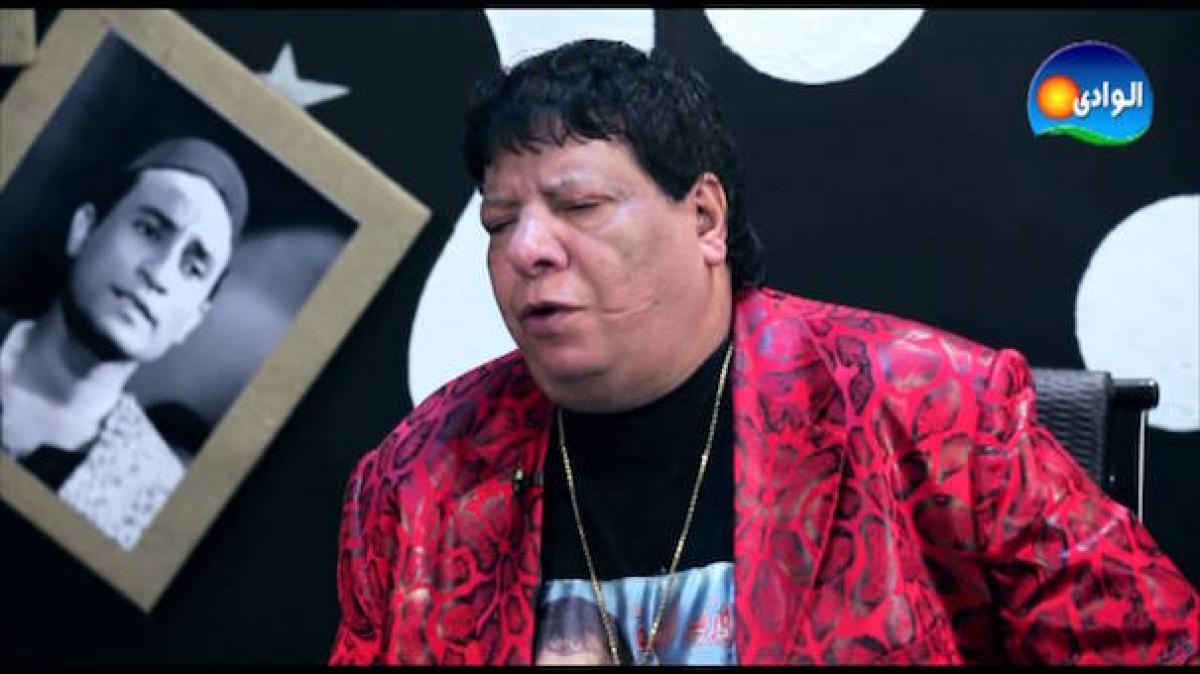

Mohamed Fouad was one of a number of popular musicians who issued a public statement praising Mubarak and hoping that he would continue to be the president, during the early days of the revolution. While Fouad was not as harsh in his comments as other artists, some of whom hyperbolically insulted the humanity of the protesters, in hindsight his comments now appear a PR gaffe. Like Amr Diab, then, there is a sense of penance in Fouad’s video clip.

Fouad’s martyr pop song, «I resemble you», is addressed directly to one of the martyrs, remarking at length on how much they looked like any ordinary Egyptian that one could have bumped into in a variety of everyday settings. (The martyrs’ published photographs enhance this impression: they are mostly not formal portraits, but informal shots of them playing on the beach, grinning at friends at a café, etc.) This ordinariness contrasts with the greatness of what the protests accomplished, which the lyrics note at the end in a deliberately vague way. These lyrics clash somewhat with the editing choices in the video, which mingles photographs of the recently killed protesters with stock footage shots of Egyptian soldiers in long-ago wars, and exemplary ordinary Egyptians who had nothing to do with the protests. In a strange intermingling, Khaled Said appears here, as well as several police officers. Oddly enough, none of the female martyrs is shown. While a few photographs are shown of events at the protests, they flash by quickly and somewhat out of focus, and none of them has any legible protest signs that might indicate what the protests were about.

Tamer Hosny, a very popular and ambitious young singer, committed a huge faux pas during the protests by going to Tahrir Square and, under government pressure, trying to convince the protesters to disperse and go home. This led to widespread and widely discussed public contempt of Tamer, unlike the relatively low-level grumblings about Amr Diab and Mohamed Fouad. Once it became clear to Tamer how badly he had injured his public image, he threw himself into a number of pro-revolutionary endeavors as PR opportunities, in an effort to salvage his reputation.

This video, «The martyrs of 25», is one such endeavor. Tamer, who wrote and composed the song himself, opted for a contemporary sound that wouldn’t be out of place in a standard-issue love song. The lyrics are quite vague about who or what the titular martyrs might be, leaving it to cultural context for the listener to understand why such martyrs are being honored. The visuals are likewise referential and vague, carefully avoiding anything that spells out the protesters’ opposition to the continuation of the Mubarak regime, much less why they had come to such opposition. The martyrs themselves, though, are clearly designated, and are depicted with their names beneath their photographs. There is also some footage of people either being shot down or their corpses being buried as national martyrs, with the Egyptian flag draped around the coffins or the bodies on stretchers.