How Does AI Hear?

AI music often sounds very familiar, because it is limited to its creators’ musical horizon. In the third essay of our «Sonic Vignettes» special, Rolf Großmann asks what happens if one liberated AI «ears» from the constraints of human sensations?

What does AI like AIVA or amperTM listen to? Does it hear Christmas bells, streetcars, children playing, or music by John Cage? No, it does hear classical music, and not just a few works, but «30,000 scores, written by the likes of Mozart and Beethoven» (Barreau 2018). So the ears of these AI have to endure a lot. For the sake of honesty we must note that, in fact, AI doesn’t listen at all, but reads. It works on the level of «high-level symbolic representations» (Briot et al. 2019, 5), i.e. digitized note values. Then, according to AIVA’s creator, to create «original compositions»:

«... AIVA looks for patterns in the scores. And from a couple of bars of existing music, it actually tries to infer what notes should come next in those tracks. And once AIVA gets good at those predictions, it can actually build a set of mathematical rules for that style of music in order to create its own original compositions» (Barreau 2018).

Artificial Composition

This evokes a sense of déjà vu, a flashback to the midcentury Pioneer Days of Information Aesthetics. In 1956, even before Hiller and Isaacson presented their famous score of the «Illiac Suite», generated on the ILLIAC-mainframe (1957), Richard C. Pinkerton used 39 nursery songs from the American Golden Song Book (ed. by Catherine Tyler Wessels) to calculate transition probabilities from their melodies to the next note in each case, and to construct a «banal tune maker». Frederick P. Brooks et al. used 37 hymns in a similar approach, and proposed a complete theory of algorithmic composition as an analysis-synthesis process in which new style-appropriate tunes are generated from the mathematically-obtained probability factors. An exciting vision at that time, but long forgotten today due to the low aesthetic value of the results.

What remains is the promise of being able to compose new «original music» artificially from a selection of samples, nowadays taken from 30,000 scores instead of 37. The range of offerings here extends from the resurrection of the masters of the Baroque or Viennese classical music to the automatic composition of new streaming hits on Spotify. The idea behind the platforms is to get copyright-free utility music for the soundtrack of commercials and videos, or for the interactively generated real-time soundscape of computer games..

More Intensity, Less Kitsch

Actually, in the whole complex process described above, we see a reduced simulation of human-composed music. Based on an algorithmic analysis of familiar material, a prediction of a new euphonious structure is generated. That allows us to understand why AI-generated music can sound unexpectedly boring. The original part of creation, the machine’s own life, or «Eigenwelt der Apparatewelt», as David Dunn put it in 1992, does not take place. AI reproduces the limitations of its techno-cultural prefigurations. Depending on what it hears and which patterns it is allowed to use for composition, more or less bad soundalikes of the respective style are created. The result is the opposite of artistic creativity; in the case Pierre Barreau is talking about, we hear the 30001st rehash of the classical-romantic era, which some people believe was more beautiful than the present.

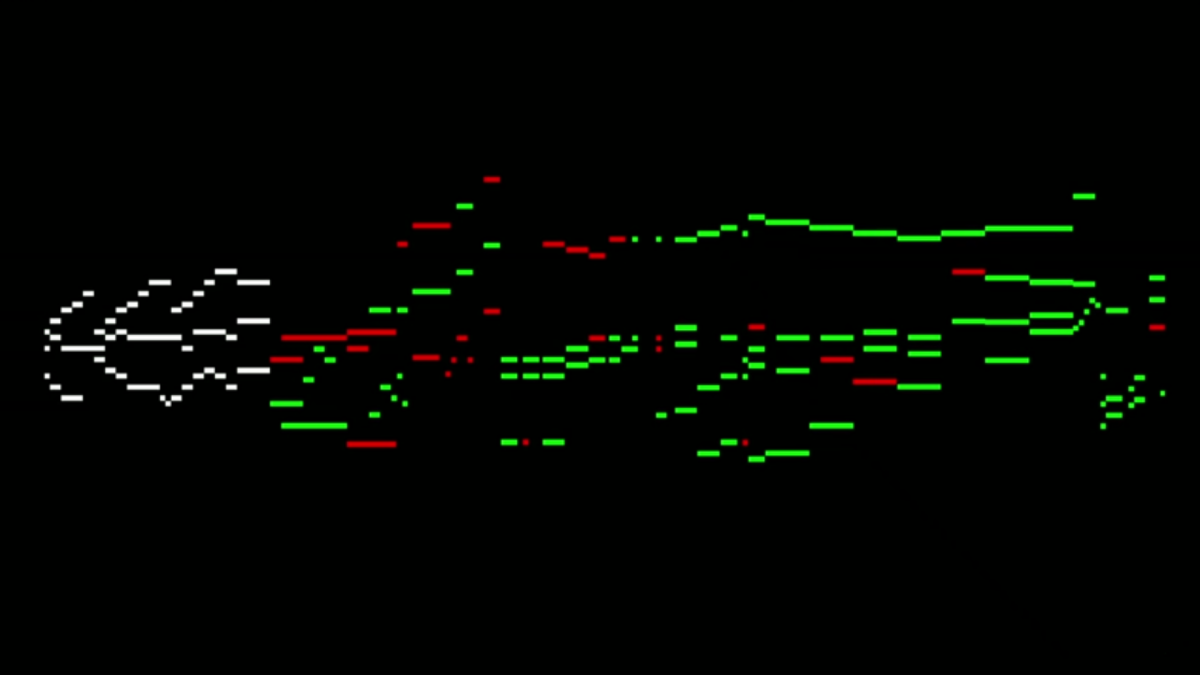

Instead of these uncanny kitsch patterns, which are nothing else than algorithmically-generated aesthetic «prediction products» of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff 2019), it would be more interesting to explore the sensory experience of algorithms, their aberrations and successes, discovering their own contribution to the intensification of our world of sound. More exciting would be music technological innovation as described by Kodwo Eshun: «Sound machines make you feel more intensely, along a broader band of emotional spectra than ever before in the 20th Century» (Eshun 1998, 00[-002]). Usually AIs are trained to listen like humans – now is the time to free their ears, listen to them, and enrich our musical practice.

List of References

«Sonic Vignettes» is a Norient Special discussing sound: one fragment, one experience, recording, one viral video, stream, one monograph or encounter at a time – in all its depth, its historical and affective ramifications, with the finest expertise in Sound Studies. Initiated by Holger Schulze, Rolf Großmann, Carla J. Maier, and Malte Pelleter, published as a monthly column.

Biography

Published on February 02, 2021

Last updated on November 05, 2021

Topic

Digitization means empowerment: for niche musicians, queer artists and native aliens that connect online to create safe spaces.

Special

Snap