In this very personal essay, Rami Sabbagh, a filmmaker and musician, recounts life events, encounters, and journeys in which music and sound are paramount. From the basement of a cassette-tape store in Damascus, to the July 2006 war, to making films in the streets of Beirut at night, he reflects on the sounds and voices that accompanied him and those that haunt him to this day.

The Father Gazes

I can’t remember the exact place or what year it was but I remember there being a loud sound. Tarek, my friend from high school, barged in and slammed a black notebook on the table. Ali and I looked at the notebook and then at Tarek, waiting to find out what it contained. This incident might have taken place after 1995 when the Lebanese government banned metal because it claimed the music drove youths to devil worship and suicide. After Tarek read to us the content of the notebook, we decided to travel from Beirut, the capital of «freedom and openness», to Damascus, the city of Assad Senior, the father, whose eyes follow you everywhere you go.

What is adolescence after the war? A prelude.

When we were in high school, after a childhood spent during the war, we unconsciously looked for a vocabulary to describe ourselves. Where did all this death come from? Metal gave us the answer to what we couldn’t say. The re-destruction of Beirut – by dynamite not bombs – and the razing of remnants from the war had ended. At the time, the late prime minister Rafik Hariri and his associates began the so-called reconstruction of the city from which new sounds emerged. We thought that the roar of drilling machines and the screech of welding equipment were only temporary but they soon became a part of our daily vocabulary to this day. During this blue period, a budding generation’s words were seen as a threat to politicians of the nascent state, there was no room for anything but: «We have to build, everything is fine, we have to build.»

Warlords placed their bodies in suits, parliament, and ministries as if they owned the city and decided to own whatever we had on our adolescent bodies, from tattoos, words, and panic attacks. In their efforts to control what we said and listened to, they lumped together different genres of music like punk rock, metal, grunge, even Jon-Bon-fucking-Jovi in the same basket (I often imagine Jon Bon Jovi begging the Minister of Interior to release him from the basket because Ozzy Osborne insisted on calling him Bryan Adams). They called these types of music «demonic spells», which made them dangerous and subversive. How could we not perceive this threat as our victory?

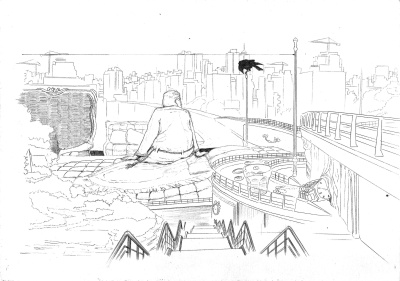

I don’t recall much from the trip to Syria except for the cassette-tape store we went to and how worried we were at the Lebanese-Syrian border on our journey there and back. On our way to Damascus, we became gradually uneasy as the picture of the father became larger and larger throughout the trip. Like a religious icon, his small portrait was present, hung on the front mirror of the taxi, glued on car windows heading to Syria, painted on murals of border walls and on large monuments in the squares of Damascus.

Upon our arrival at the store, we went down a long staircase that led to a large warehouse where thousands of cassette tapes were stored. We didn’t know what to do with such a large number of songs. The employee put our hesitation to rest when he told us that he had different, better quality cassette tapes called Chrome. He then directed us to the shelves. I remember how comforting it was to obey the movement of his finger. After we left the store, having purchased what we wanted, I spotted a piece of paper glued on the store window that read:

«For God’s sake, we don’t sell Hani Shaker».

On our way back, we broke out in a cold sweat because we had a non-negligible amount of «dangerous» and banned material in our possession. We had bought tapes with covers featuring devils and angels of different shapes and religions. What made things worse was that Tarek also had his black notebook, which turned out to be the official notebook of the store we went to. It contained the store’s entire music catalog, among which were the banned metal bands in addition to a large number of groups that the Lebanese Minister of Interior did not know about.

We deemed ourselves fortunate when the government thought we carried the devil on cassette tapes. It had a profound effect on how dangerous we thought a song could become. The government banning metal and its sister genres was both a victory and a defeat. It was a victory because the state had announced that our tastes were more dangerous than the law or religion but it was a defeat because that ban had eradicated the possibility for my generation, who spent its first years listening to the sounds of bombs and screams, to speak. From then on, song became our weapon just as the sounds of the city became theirs.

Stockhausen and Christian’s Sharp Teeth

Christian was angry at everything. He moved his jaw from left to right as he watched from the café the movement of cars passing by in the late afternoon. In every film I make, I insert the sound of cars like the ones that drove by the café. Perhaps it’s because it’s one of the few warm sounds that the city has given me or perhaps it’s because I want to sit next to him again. In a café full of young people, he told me about his encounters with Chris Marker and Joris Evans in Paris and how he hit the writers of Cahiers du cinéma in a fight over Mao Tse Tung. When I tried to find out why he later rejected Trotsky, he told me: «Do you know what permanent revolution is? The sun!»

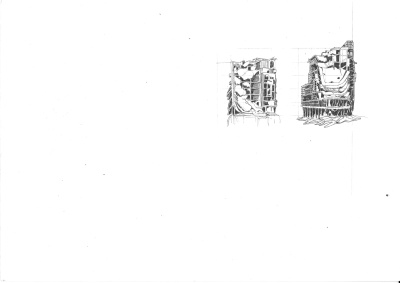

From time to time, Christian moved his lower jaw from right to left to fix his denture in its place. His tongue moved slowly in his mouth while his hand held his head. But something in his eyes fixed something far more dangerous. It’s as if the denture’s escape from his jaw reminded him of time’s escape from his life: when he stopped making films after the siege of Beirut in 1982 and when he decided to stop working and sit in cafés after two mercenary extremists burned all his books and films in 1986.

In 2002, Elias el Murr, like his father before him, decided to wage a new campaign against metal in Lebanon. I headed to Syria once again. Its president Bashar al Assad inherited the position from his father Hafez el Assad. On this second trip, I did not look for angels or demons but went there for Christian’s sake with my friend Raed. After a six-month-long wait, our friend Bassel had called us from Syria to tell us that he had found a copy, perhaps the only remaining copy, of Christian Ghazi’s film Hundred Faces for a Single Day in the public cinema archive in Syria. The film was shown in Damascus in the framework of the International Film Festival for Young Arab Cinema 1972 after which the Syrian authorities confiscated the film, banned its screening and distribution, and the film disappeared from circulation. To them, it was a «dangerous» communist film. And just like that, the life of this film, one of the most significant political avant-garde films in Arab cinema, had ended. Raed and I stood in the studio of the cinema archive and watched as a machine transferred Christian Ghazi’s film to a video cassette.

As the credits appeared on the screen, we waited for one name: Karlheinz Stockhausen’s. Christian had told us that he was his friend and that he had asked him if he could use his composition «Hymnen» in his film. But when Stockhausen’s name appeared, we realized that we couldn’t hear the film’s sounds, all we could do was gaze at the needle of the sound equipment to control the quality of the sound transfer.

The portraits of the father and son hovered above us as we listened to the most important soundtrack in Arab cinema in silence. We were unable to ask for anything, let alone speak, we could hardly believe that we had found a copy of the confiscated film under a pile of dust in the darkest basement of the archive. This is our lot: we engage with our near past as if it had been absent from us since ancient times. We look for our music and films as if we were looking for ancient artifacts and smuggled them like thieves. We steal the writing of history from the theft of history.

When we brought the film back to Beirut, Christian moved his lower jaw from left to right as he watched it for the first time since 1972. What did he remember when he saw those images for the first time in thirty years? When the film ended, he didn’t say a word. He moved his lower jaw from right to left to the rhythm of the passing cars driving past the café in the late afternoon. I think I use the sound of those cars in every film because I am always returning to his jaw.

The Smell of Rotten Metal

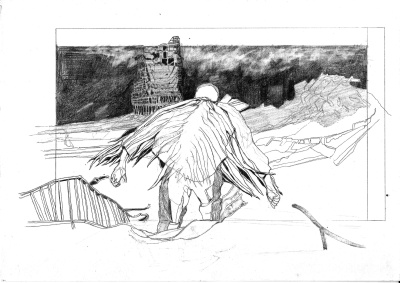

One evening in July 2006, I opened the window and put my fingernails, which I hadn’t cut in months, on the glass windowpane. I bent over to bring my ear closer to both the small opening and my nail. I touched the glass window and compared the sound of the falling Israeli bombs on the southern suburbs that resonated from the small opening of the window and the reverberating sound of my vampiric nail on the glass pane.

The meaning of the word «rocket» (saroukh) in Arabic comes from «to scream» (surakh) and people used to call the high-pitched bamboo mizmar (a double reed wind instrument played in Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean) al sarouhka. A rocket screams before and after it falls. As for the metal welding machine that screeched throughout the city after every war, it is also called a rocket (saroukh). That is how we live in the city, we go from one rocket to another and carry our screams with us.

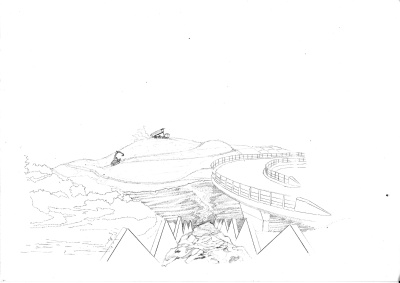

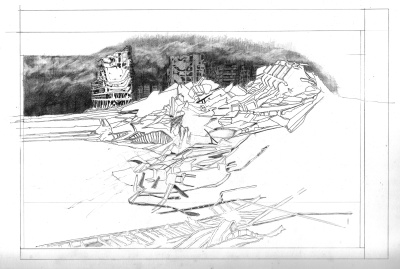

I dragged my other hand across the entire glass window and stood bare-chested in front of the open window smelling the wafting odor created by the destructive sounds. In moments like these, when sounds of bombs, fireworks or music from a strange underground concert intensified at night, my color blindness intensified with them. That night, Beirut turned into gray hills and the missiles turned into snow, failing to fall quietly on the ground.

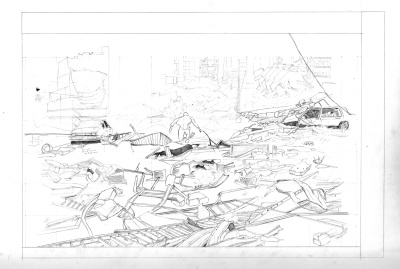

After that July evening, Beirut had reverted to a regular city that awoke from the screech of welding machines. Their sounds rose all day long, and chased the city’s residents towards the sea or the airport. I couldn’t move around in the streets without toxins infiltrating my veins and when they fell silent for a while during suspicious moments of political anxiety, a car exploded, almost out of boredom.

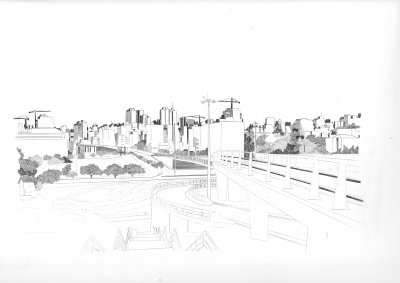

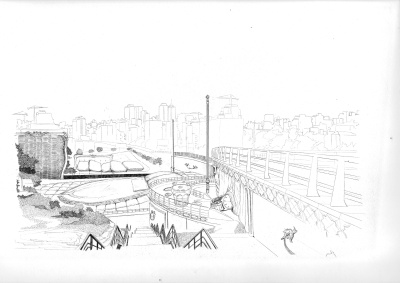

At night, another city emerges. It’s inhabited by those whose work stole their sleep, returning to their homes exhausted and disquieted. They find their way home to the iridescence of billboards that glistens on the asphalt of roads. Among all this ash, I decided to build my garden. I put my camera on the side of the road, recording the movements of objects and their shadows.

How can the camera see what I see? I switched the recording to a slow shutter speed so the movement of objects appears choppy, as if a crack had been created whilst moving from one moment to another. Between each image is a rupture of time that disjoints in the city of gray shadows. How can cinema fight time? Does this medium, full of time, have the ability to withstand the weight of every moment? It’s a rupture followed by a rupture. After days of recording, the ruptures accumulated and became a horizontal body of absence. An open space of darkness that serves as a night garden, like the public gardens that my friend Raed and I used to frequent at the end of the night. I invited Rayya to the shoot and asked her to sing behind the camera while it was recording. She had to be present at the genesis of the garden’s creation to give it a scent. The camera recorded all this absence while she enveloped the ruptures with pop and post punk and I tasted bad blood in three dirty films in the midst of this noise.

What Do I Put in My Mouth?

Isn’t it nice when a bureaucratic clerk hums a song while doing his hateful job – pulling himself out of daily death with a little George Wassouf? Much of what has been said on art as an act of resistance is performed in this movement of lips, the bureaucratic clerk’s amusement is a vengeful act against the state.

When an actress looks at the camera and begins to sing, cinema takes off her storyteller’s robe and she returns as an erotic dancer. The actor is freed from his job as mediator of desires and becomes himself the desire in both erotic and political senses. Allow me to explain how this friction works. In Ghassan Salhab’s fiction feature film Terra Incognita (2005), writer and artist Walid Sadek plays the role of Nadim, an architect who rebuilds the city he lives in virtually on his computer screen. For most of the film we look at the ghost of Walid Sadek masquerading as Nadim who is unaware of our presence. Except in one scene where Nadim sits in the bar with a friend, looks at the camera and starts singing a playful parody of a patriotic song. In that moment it is possible to recognize that it is no longer oblivious Nadim but the ghost of Sadek challenging the tyranny of narration and gazing through the screen into our eyes turning us into ghosts as well. In this joker act of defiance of both the narrative from and of the patriotic song, filmmaker Salhab and performer Sadek expose the latent quality of a filmed face as a political landscape that is grounds for tension between submitting to the filmic text or ghostly rebellion.

After making three grainy films to ward off the noise, I decided to move away from nonfictional experimentation to make narrative films full of song, starting with a film starring Ziad Chakroun and Sandy Chamoun in which the two meet in almost miraculous singing scenes. I wanted singing to be a declaration of love that felt like the fall of eternity into time, as Alain Badiou puts it in his book In Praise of Love. Similar to the ecstatic moments of participating in a revolutionary political act, the characters overcome their conspiratorial reality through song and love as fragments of political miracles.

I walked around the city day and night, stealing scenes everywhere and saw Ziad and Sandy in every bar I entered. I heard their voices in every love song – even the bad Christian songs that I liked to listen to when I drove at night. I saw their two bodies embracing inside every car that passed through the light changes of Beirut’s tunnels.

On a hot summer afternoon, while I waited on the corner of the road for a taxi, I looked up and saw a billboard with an ad about insect repellents. Sweat began to trickle down my forehead and eyes from the intense heat. For a brief moment, I lost my sight and Ziad’s face and angelic smile began to appear on the billboard and he opened his mouth to sing George Wassouf’s «Helef el Amar». I too started to sing and as I was finishing the song with a panting breath, a huge white truck screeched past me and honked so violently that it shattered my song like glass just as the diffracted light from its windows ripped out my eyes. I put my hand on my ear in pain and the other on the floor and I knelt crying from fear of losing my hearing.

My ears rang for a whole week. When I calmed down, and to assuage my fear, I decided to wear earplugs outside during the day. I discovered that isolating my ears decreased the intensity of the summer heat and that covering them not only protected me from the sounds of the city but from its violence as well. Since that day, no cars have exploded in Beirut.

I began to hear my feet stomping on the roads. I could even hear them in the noisiest neighborhoods, which made imagining the music of my new film amusing, with repetitive electronic pulses like the ones I made with each step. I joked to myself that the city agreed with me on my decision to compose synth-pop versions of George Wassouf and Mona Maraachli’s music for my film. The first version of the script was completed and as soon as I started working with the musicians on composing the score, events unfolded in 2019 and again in 2020 after which everything stopped working. But the chants that surrounded the demonstrations showed me that singing was still crucial and I kept seeing Ziad and Sandy singing and falling in love everywhere.

On August 4, 2020, a glass pane fell on Ziad’s body, tore his back, and a sound entered every home in Beirut, shutting everyone up. Since that sunset, and every time a scene from the film appears in my mind, I see Ziad and Sandy standing in front of me side by side, without moving. Sandy opens her mouth without making a sound and holds Ziad’s hand, who opens his mouth but he has no tongue. They are standing on black, sunburnt asphalt, with two black holes on their faces where their mouths are supposed to be. The two holes look like two eyes and the asphalt draws a burnt upper mouth, this new face looks at me waiting for a song. It’s waiting.