The Poetry of Noises

The noise music community of Indonesia might look like a gaggle of misfits, but Gisela Swaragita found them surprisingly welcoming. These encounters taught her how to welcome everyday noise into her life through elevated listening, a practice replicated by Adythia Utama’s short film existence.

→ Check all articles of this special

→ Download PDF with introduction and table of contents

«Jogja is a noise city», says a man in Dan Jay Stockmann’s 2018 eight-minute film Noise. As a Jogjanese born and bred, I can confirm that the statement is true. All my life, I have lived in a crowded labyrinth-like community area known locally as a kampung, situated at the heart of the city. All kinds of weird noises find their way into the privacy of my bedroom, from the shrieking of my neighbor’s baby to the sound of a wandering bakso meatball soup seller announcing his presence in the narrow streets by clanging a tin spoon against a ceramic bowl. Even in the most silent moment of the witching hour, while you lie awake in bed, you might hear a mysterious marching band, believed to be the lingering ghosts of Dutch colonialist soldiers.

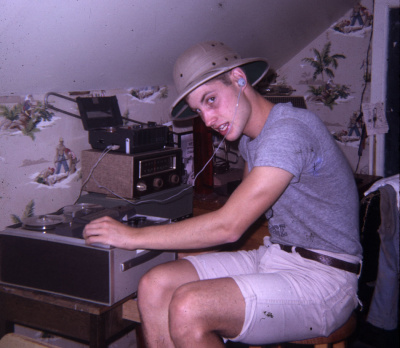

While noisy environments have become native to me, for a long time I couldn’t relate to noise as music. I found it suffocating and dizzying, almost like an under-researched, foreign pollution. I could not understand how something so rampant around my home could be framed, staged, and appreciated as a work of art. But the noise scene in Jogja is huge and growing rapidly because it is very accepting of any kind of person. In my younger days, I took refuge in this. In my formative years from 2013 to 2017, I attended noise gigs every week. Artists clanged metal barrels with baseball bats on stage, or abused the strings of electric guitars connected to various effects pedals while wailing tormentedly into a beaten-up microphone. I saw the audience go crazy and climb on each other’s heads in the mosh pit to the heat of the violent sound. I always clapped enthusiastically when the set was over.

I clapped enthusiastically because the set was over.

The Acceptance Stage of Noise

Noise was tormenting for me, but I was amazed by how it created an environment so accepting, making it possible for anyone to create a stage for any kind of bizarre behavior. Perhaps because the community offers unconditional friendship, I, in turn, slowly tried to enjoy noise as performance. Before realizing it, I became more sensitive to the various sounds in my daily routine, appreciating them as a form of complex sonic experience. My slow-growing love of noise peaked when one day I found myself enjoying the humming of my family’s 29-year-old refrigerator!

I watched Adythia Utama’s short film existence. at the perfect moment. I was already prepared for the aesthetic of noise, especially when diluted as a companion to moving images. existence. invites you to experience the miles Utama traveled from Jakarta, Indonesia, to other cities abroad, compressed into a seven-minute video scored with melancholy hums and occasional harsh noises. The demoniac mechanical uproars that used to be appalling to me add a dramatic atmosphere to the flashing scenery seen from moving trains, the flow of people walking in busy streets, and glimpses of exotic foreign landscapes.

A Place for Every Noise

Just as the film is a collage of Utama’s memories of past travels, it brought me back to the days I made friends with some of the Jogja noise community. Then a twee girl in my early 20s with wide frame glasses and short bangs who only listened to sad indie pop, I mingled with people sporting other distinct features with references from other subcultures: Foreigners with tribal tattoos all over their bodies and piercings all over their faces, metalheads with frizzy hair, girls and boys in colorful handmade garments and accessories, and even «normal»-looking friends who brought their prayer rugs to the venues so they could still pray five times a day. A collage of weirdos in the eyes of the locals, we always made a scene everytime we went to the nearest food stall for cheap iced tea after an intense gig.

These misfits, however, taught me that you can upgrade from only hearing to listening. Now I can listen to any kind of racket and clamor I find in my daily life, and enjoy it too. Every mundane thing in life is a stage for noise music, if only you listen closer. I have succumbed to the poetry of noises.

The film «existence.» by Adythia Utama was officially selected at the Norient Film Festival NFF 2021. See full program here.

This text is part of Norient’s essay publication «Nothing Sounds the Way It Looks», published in 2021 as part of the Norient Film Festival 2021.

Bibliographic Record: Rhensius, Philipp. 2021. «Editorial: NFF 2021 Essay Collection.» In Nothing Sounds the Way It Looks, edited by Philipp Rhensius and Lisa Blanning (NFF Essay Collection 2021). Bern: Norient. (Link).

Biography

Published on January 19, 2021

Last updated on June 28, 2023

Topics

Does a crematorium really have worst sounds in the world? Is there a sound free of any symbolic meaning?

From Bangladeshi electronica to global «black midi» micro scenes.

Why do people in Karachi yell rather than talk and how does the sound of Dakar or Luanda affect music production?

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

Snap