Folds of Time: Delhi in the Memory of Qawwals

The soundscape of a city is essentially ephemeral – it is an accumulation of sounds layered one over the other that constantly emerge and disappear. At the same time, there are musical traditions that seemingly do not belong to the modern soundscape of the city, but evoke a nostalgia for something in the past. A past that is lost and yet always evoked in song. This essay will consider the performance of Qawwali in South Asia and its reference to the lineage of Delhi. It will also look at the Sufi singer, poet, and scholar Amir Khusrau,1 whosesongs bear the trace of a lost time. In this piece, we will observe how in memorializing the past, Delhi emerges in Qawwali not as a location or an identity or a descriptive category, but always as a space of desire.

City and Memory

No city is ever generally beautiful. There is no abstract beauty of a city unless it is the immortal city of God. For us mortals, a city always presents something concrete and particular. It offers something singular, some particular beauty of circumstance or immediacy which is always invested in the present moment. The city of Delhi is no different. A vision of the bus stand in Chandni Chowk,2 a certain aroma in the back alleys of Jama Masjid,3 the sound of azan while waiting at the red light along Chirag Delhi4 – these are sensations of beauty which are neither general nor abstract. It doesn’t matter whether such sensations represent the past or the future. On the contrary, the pleasure we derive from them has the essential quality of their being in the present. Charles Baudelaire once wrote that «beauty is always and inevitably compounded of two elements, although the impression it conveys is one» (Beaudelaire 2006, 392). This double composition includes an eternal and an invariable element on the one hand, and a circumstantial element on the other hand. Whereas the former, being timeless and absolute, is difficult to determine, the latter always bears the mark of time and is relative to an epoch. Without the latter, he says, the former would be beyond our appreciation.

The sound of Qawwali which fills the bustling complex of Nizamuddin dargah5 in Delhi bears testimony to this double composition of beauty. Interwoven with the myriad soundscapes of the city, the beauty of these mystical tunes lies in the ambiguity that they express.

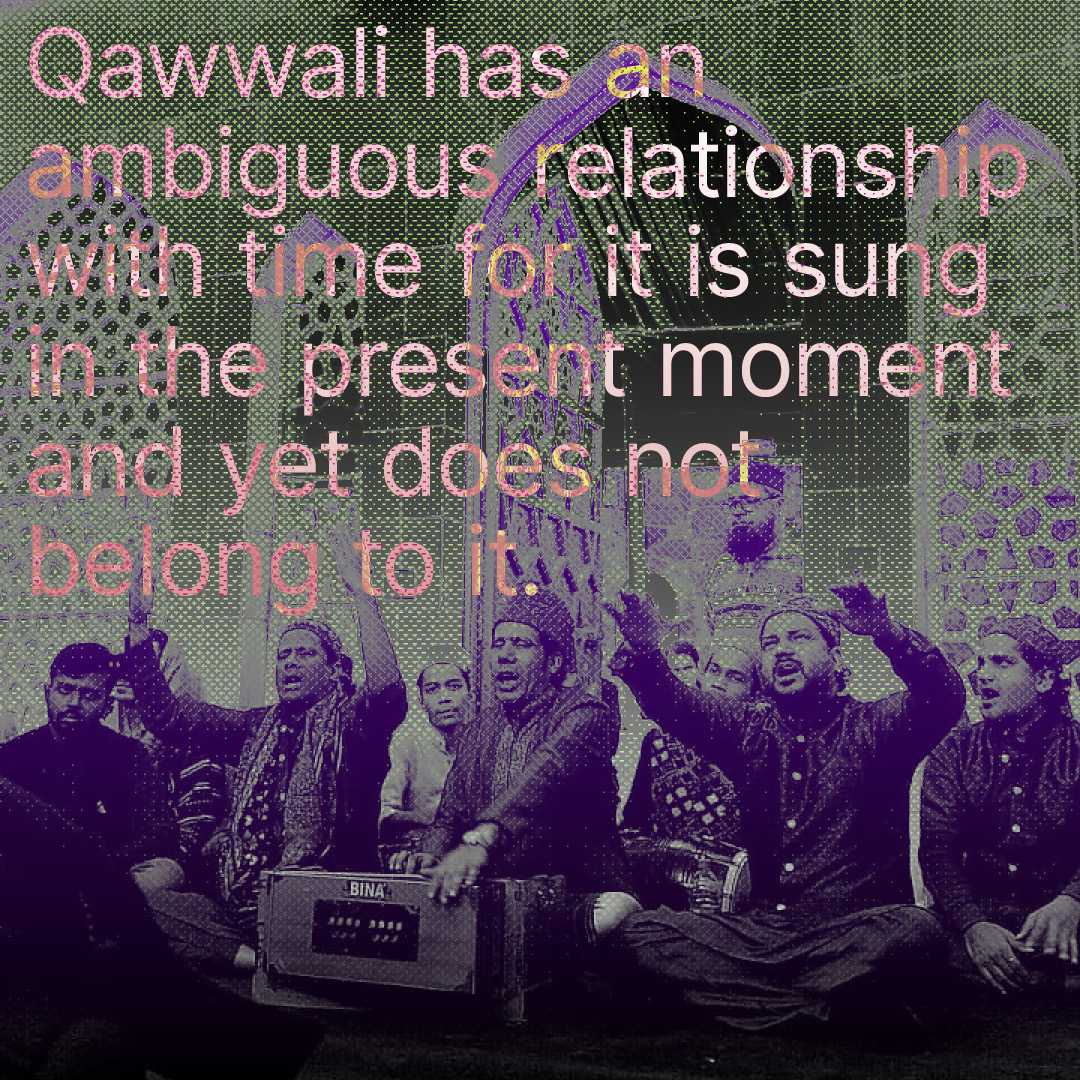

Qawwali is a musical genre specific to a Muslim Sufi tradition. It involves singing poetic verses or couplets (known as kalaam) in Persian, Hindi, and Urdu that evoke feelings of divine love, longing, and ecstasy. These songs are central to the ritual of Islamic mysticism in South Asia and are considered a powerful medium to attain union with God. Performed to date in ritual settings in Sufi shrines (mausoleum of a saint) as well as on professional stages, one can argue that Qawwali has an ambiguous relationship with time; it is sung in the present moment and yet does not belong to it.

The voice of the Qawwal does not belong to our epoch. It is not stamped by our time because it is a voice coming out of the past, marked by the memory of the 12 singers believed to be taught by Amir Khusrau himself, which still echoes among the Sufi shrines. These singers were known as Qawwal bachche, (the Qawwal offspring). It is claimed that for 700 years, descendants of this unbroken lineage have been practicing the Qawwali tradition and somewhere in their kalaam lingers the scent of the river Yamuna where the essence of Sufism was articulated by Amir Khusrau and Nizamuddin Auliya.6

City and Voice

The verses in the voices of Qawwals distill the beauty of the past as if it were being performed in the present. More than being a mere representation of a tradition that is invested with grace and beauty, these kalaam evoke the very experience of the history of Qawwali. The sound of Qawwali is encountered in the present as something particular, concrete, and real among so many singular voices that a city space produces every day. Qawwali carries within itself the memory of another city. It becomes equally ephemeral, belonging to a bygone epoch and an elsewhere place. It is the unfolding of such a memory that activates our desire for a Delhi which is not there; like the great Mughal miniaturists, these voices paint images of time with sound.

In the end, one is reminded of the following couplet of Khwaja Nazir Nizami:

bani dehli dulhan doolha nizamuddin chishti hai

zamaana bhar baraati hai nizamuddin chishti ka

(Delhi has become a bride and the groom is Nizamuddin Chishti / the entire world takes part in the wedding procession of Nizamuddin Chishti)

It is as if the whole world gravitates towards the city while the bridal city seeks out its beloved – the voice which sings of Nizamuddin Chishti. The entire cosmos folds into the city that seeks something more pure than itself – something that lies elsewhere. And this continuous displacement, this desire for an elsewhere, is what the voice of the Qawwal evokes.

- 1. Amir Khusrau (1252–1325) was an Indo-Persian Sufi poet who enjoyed the patronage of several rulers from the Delhi sultanate, the Muslim empire that was established in the 12th century and had its base in Delhi. He was also the most famous and beloved disciple of the Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya. Amir Khusrau is considered to have made remarkable contributions to the evolution of various poetic, literary, and music forms, Qawwali being one of them. His verses and compositions form the core repertoire of Qawwali songs.

- 2. Chandni Chowk is one of the oldest markets in the heart of Old Delhi whose busy narrow lanes still carry the flavor of the city of Shahjahanabad (as Delhi was called in the 17th century). It was established when the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan shifted his capital from Agra to Delhi. Designed by Shah Jahan’s daughter, Jahanara Begum, this market literally means «moonlit bazaar». It got its name from its architectural design as the market was built around tributaries of the River Yamuna such that it would reflect the moonlight and add to the elegance of the area. Though this architectural ingenuity has changed over time, the bustling market retains its uniqueness for heritage shops still famous for selling dry fruits, spices, jewelry, clothes, essential oils, and traditional Indian sweets. What adds to the charm of the market is the 17th-century Mughal fort called the Red Fort that overlooks the market and the Fatehpuri mosque on the other end, which was built by one of the queens of Shah Jahan.

- 3. When one visits this beautiful mosque, one of the biggest in South Asia, also located within the historic Shahjahanabad city, one cannot miss the narrow streets and alleys of the area crowded with eateries and bakeries that take you on a Mughlai gastronomical journey. The food enthusiast who roams these lanes following the aroma of kebabs and curries relishes the appetizing flavors that once filled the kitchens of the Mughals.

- 4. An otherwise densely populated part of South Delhi, Chirag Delhi gets its name from the Sufi saint and poet Hazrat Nasiruddin Chirag Dehalvi whose shrine is nestled in a secluded corner of the area. Although several localities, neighborhoods, and flyovers have sprouted in the vicinity, this shrine hidden amidst old gigantic trees provides a beautiful solitary interruption in the hustle and bustle of the city. The sound of the azan, the Islamic call to prayer, from the nearby mosque further accentuates the melancholic strain that a city amidst all its rush hides deep in its heart; a melancholy that does not depress but illuminates the mind towards something outside, something that cuts across the repetitive city lives, making this feeling almost true to the name of this place Chirag Dehli, the illuminated lamp of Delhi.

- 5. Nizamuddin Auilya (1238–1325) was one of the foremost saints of the Chishti Sufi heritage in South Asia. The Chishti school of the Sufi mystic tradition emphasized values of love and tolerance. It placed importance on evoking and experiencing God through music and poetry. Qawwali therefore evolved as ritual musical assemblies, where though poetry of abandonment and love for the divine, one could immerse oneself in devotion and spiritual ecstasy. Since the 13th century, the shrine (dargah) of Nizamuddin Auliya has remained an important center of Sufi tradition. Apart from his tomb, the shrine complex also has the tomb of his beloved disciple Amir Khusrau. Even now, every Thursday Qawwali is performed at the dargah and people come from all across to participate in the ritual gatherings.

- 6. Qawwali singers across South Asia, for instance Fareed Ayaz and Abu Mohammad from Pakistan, trace their lineage to the Delhi school of Sufi tradition nurtured by Amir Khusrau. In Delhi, the hereditary performers of Nizamuddin dargah hold the title Nizami to show their association with Nizamuddin Auliya and their family ancestry which they trace to Qawwal bachche.

This essay is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Delhi», curated and edited by Suvani Suri.

Project Assistance: Geetanjali Kalta

Graphics/Visual Design: Upendra Vaddadi, Neelansh

Mittra Audio Production: Abhishek Mathur

Video Production: Ammar

Biography

Shop

Published on September 29, 2023

Last updated on February 21, 2024

Topics

Special

Snap