Peru-born and Germany-based ethnomusicologist Julio Mendivil performed with folkloric groups on the streets and squares of Germany to earn his living. His short insider-ethnography discusses how Andean musicians changed their repertoire to meet German tastes, how they kept adapting to the latest trends, and how they even influenced music production in their Andean home countries. From the Norient book Seismographic Sounds (see and order here).

In his ballet Les Indes Galantes (1735), Jean-Philippe Rameau represented Native Americans as passionate courtesans who fought for the affections of their beloved. Surrounded by a colorful scenography and exotic costumes, Incas and North American Indians danced elegantly and delicately on the stage to enchant European audiences. Today, South American musicians are constructing an image of American Indians as bon sauvages in German pedestrian zones. Though they have been performing in the streets of Germany for the past forty years there are still no sociological, musicological or historical studies about them. Therefore I decided to write this short ethnography, using my personal memory and my experience as a charango player in such bands.

Interferences Between Diaspora and Home

Formally this current «Indian music» in Germany is linked to Andean music, although it contains several elements of pop and new age music as well. From the beginning the majority of groups played instruments such as the bamboo flute quena, the panpipes siku, the cylindrical drum bombo, and the chordophone charango – not a traditional combination for most ensembles from Andean countries like Bolivia, Chile and Peru. Musicians started performing in this setting in La Paz after the nationalist revolution of 1952, forming so-called folkloric groups (grupos de música folklórica), basically urban ensembles playing folkloric music for urban audiences. In the 1960s these groups had arrived in Paris via Buenos Aires where they gained popularity as exotic musicians. Fernando Ríos documented in detail how groups like Los Incas, Los Calchakis, Urubamba (who recorded «El Cóndor Pasa» with Paul Simon), or musicians like Uña Ramos settled in France and influenced the street musicians I, three years later, was going to play with.

Back home this first generation of diasporic groups influenced upcoming groups like Quilapayún, Illapu, and Inti Illimani. These groups became the voices of the musical and political movement Nueva Canción Chilena, heavily supported by Salvador Allende’s government. After the coup d’état of Augusto Pinochet in 1973 these ensembles had to leave Chile and migrated to France and Italy as well. South American folklore music in Europe therefore became associated with left-wing politics, while back home the majority of traditional musicians would identify themselves neither musically nor politically with these groups at first. This changed in the 1980s when urban folkloric groups like Los K’jarkas and Savia Andina reached vast popularity in all Andean countries. Influenced by the diasporic groups from Europe, they initiated a pan-Andean musical movement called «música latinoamericana» – a term pointing out that this was not traditional Andean music.

Urban Non-Professional Natives

When I came to Germany in the 1990s, Andean groups lived and worked throughout Europe. Groups like Los Incas and Los Calchakis or the Swiss quena player Raymond Thévenot performed on big stages. The groups I played with however performed on the streets. I performed mainly with the Peruvian flutist Teobaldo Martínez of Urubamba and composer and singer Sixto Ayvar of Alborada. Our repertoire consisted of the urban Andean music – the «música latinoamericana» – from Bolivia, Ecuador and to a lesser extent from Peru. Peruvian music was either too modern (played with European instruments like the harp and the guitar) or too indigenous and regional for the cosmopolitan character which this «Indian» music was supposed to have. We made money not only from playing, but above all from selling cassettes and later compact discs – each player would earn around one hundred Deutschmark during week days, four hundred on weekends, and one thousand at Christmas. The majority of the musicians were not indigenous, but urban people from Lima, La Paz or Quito, often sons of Andean immigrants. While I have been a professional charango player in Peru, most of them had no musical training and learned to play Andean music in Europe. They did not have any artistic ambitions, and most were also very conservative people who did not at all identify themselves with the leftist movements in Latin America. Our European spectators, however, saw us as politically progressive individuals.

Urubamba guitarist Carlos Vila was one of the few musicians with an academic musical education. Unfortunately his excellent fingering technique and finesse created problems, because on the street it was not possible to hear Carlos Vila’s guitar. We placed a microphone next to his guitar, simplified the harmonics, and sometimes even added a second or third guitar. Later we also performed with electric bass and a keyboard. Amplification transformed this music rapidly. I remember one song that revolutionized the scene: «Llaki runa» by the urban Bolivian group Mallku. This song originated the new musical formula: minor melodies which evoke Andean pentatonic music and corresponded perfectly with the European taste. Accordingly, Alborada later included popular songs like «Dust in the Wind» by Kansas and «Winds of Change» by The Scorpions in the album Melodías del corazón (2000). These «Melodies of the Heart» are not Andean, but pretend to be Andean.

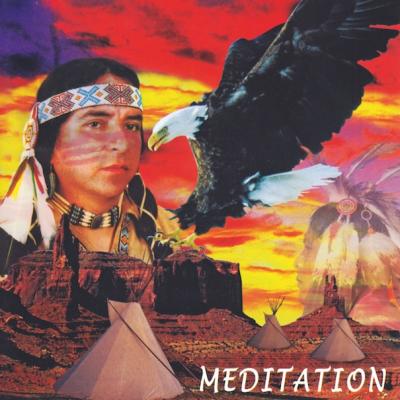

I already had left to become an academic when the German composer and producer Oliver Shanti very successfully combined meditation music with North American Indian music. Groups like Sixto Ayvar and Alborada, inspired by this recent trend of new age music, published the album Meditation in which they mixed Andean pentatonic melodies with pseudo North American songs like «Heya Heya» or «White Buffalo.» In order to reinforce the supposed union of the two indigenous Americas, Alborada began using North American Indian clothing for street performances, which led to high success in German pedestrian zones. They sold hundreds of compact discs every weekend. Now it is common to see artificial South American Indians with feather headbands who play Indian Music invented for European audiences.

Incapaches and Mega-Indios

Why do German people love these «false» Indians? My hypothesis would be that these musicians confirm the historical imagination of Germans of American Indians. Growing up reading fantastic Western stories by Karl May, many Germans see American Indians in a very romantic light, equating them with respect for nature and spirituality. They also see American Indians as victims of oppression and dispossession by European colonialism. Through conversations with pedestrians I experienced that many Germans thought we were poor indigenous people who needed their support and solidarity–despite the fact that we played with very expensive equipment. Did they need us to be poor people to whom they could be generous? In this sense, in order to be successful in Germany, «Indian» groups keep nourishing these cultural clichés.

There are of course critical voices speaking against the perpetuation of these «gallant Indian» representations. Some Latin American immigrants argue that those groups are misleading their German friends. Nicknames like incapaches (a mixture of Inca and Apache which sounds like incapable in Spanish) or mega-indios show that many Latin Americans do not welcome this representation. They denounce the appropriation and instrumentalization of indigenous culture by urban Andean musicians in the diaspora. What these objectors do not see is that many of these musicians of Andean descent were victims of what is called silent racism, which imposed a politic of whitening and negation on their Andean identity. Thanks to the romantic image of the American Indians painted by the German society, these Andean musicians for the first time have the opportunity to construct a positive identity as «Indians». Whereas they still are «primitive», uneducated, and uncivilized in their own country, they are bon savages, nature bound, and gallant as the Indians imagined by Rameau. I am not sure if I want to criticize that.