A Voguing Oasis in the Mountains

Vera and Diana walk us through their journey with the Ballroom scene in Bogotá, Colombia. As they delve into Bogotá’s contradictions of inequality and resilience in diversity, they reveal how a local Ballroom is created adjacent to music genres like merengue and perreo. This essay reviews literature and previous visual archives on ballroom culture in New York and Bogotá, identifying shared meanings, discontinuities, and local innovations.

encuentre una versión en español de este texto aquí

We are an unusual couple in our subdued society. Inhabiting the streets, even the party, is challenging. The looks, whispers, and giggles, among other things, serve as a constant reminder that something, in their eyes, «isn’t right» with us. Despite this, we have been walking this path together for nearly eight years, and while diverging from the heteronorm, we have entered into a dreamlike world inhabited by fantastic creatures that, like us, delve into the depths of this mountain in search of the light and warmth of self-celebration. We want to share a part of this voguing oasis that we have known together, to transmit the aesthetic, political, and sound richness being breathed into Bogotá’s Ballroom culture.

Ballroom originated in Harlem, New York in the late 1980s as a way for gender and sexual minorities, mainly Black and migrant trans women, to challenge the prevailing framework of racism, patriarchy, and heteronormativity. Although it is a space for celebration and fantasy, its structure has institutionalized categories, rules, and customs that have persisted to this day, albeit not without resistance, spreading to new contexts and territories.

Ballroom is often considered a «queer heritage», where voguing1 and performance are used as tools to challenge the social and cultural expectations of gender, resist the norms that oppress marginalized bodies, and imagine new ways of existing beyond the usual frameworks of exclusion and violence. It is a space where, as Nicole Flórez Cruz (2023) has suggested, a community of affection can be formed, where marginalized communities, including Black, cuir (queer), and impoverished people, can find a sense of belonging and restore dignity to their lives through their chosen families and casas (houses).

Our Body Is Our Manifesto

In Bogotá, the ancestral legacy of resistance has been revived to create a new version of Ballroom incorporating different political tensions, movements, aesthetics, and sounds. This unique version of ballroom culture celebrates the unconventional, dissident, and unclassifiable.

Around 2016, the House of Tupamaras emerged as a significant artistic and political force in the flourishing ballroom culture of Bogotá, the first ones in the city who saw themselves in the lineage of this queer heritage. Inspired by the well-known merengue orchestra from Bogotá and the name of the disbanded Uruguayan guerrilla group Los Tupamaros, they identify themselves as a «queer guerrilla» group whose manifesto is dancing. They introduced us to voguing and Ballroom. Every Thursday afternoon, mariconas2 of all backgrounds, including us, gathered to learn how to walk the runway and vogue in one of the traditional «de ambiente» (euphemism used for «gay») bars downtown, where decades ago, people with non-normative sexual orientations and gender met clandestinely due to prohibition.3

Becoming familiar with the «vogue beat» was no easy task, but like a baby learning to walk, we played at falling awkwardly in time, going through the motions first with sounds and tempos we were familiar with: merengue and perreo (reggaeton and Latin urban style).

The Ballroom was something we felt fit perfectly into the queer and alternative scene of Bogotá, a chaotic city surrounded by mountains, overwhelming, contradictory, unequal, but resilient, countercultural, a meeting point for a thousand and one ways of existing. Although the pandemic took us off the streets, the social outbreak of 2021 led us to flood them again. In the context of the national strike, voguing reached unprecedented popularity. Las maricas began to create houses, gathering at demonstrations such as «kiki balls»4 to learn and vogue together in public. In practicing this«guerrilla art» style, we were trying to resist repression from these new codes that we gradually made our own.5

In this video uploaded by Piscis, she and two of her friends Neni and Axid break into the steps of the Colombian Congress in Bogotá during the 2021 national strike, jumping the security cordon of riot police. Covering their bodies with danger tape, they perform vogue choreography, with Colombian electronic music (guaracha), raising a Colombian flag and being cheered on by protesters. This footage represented a milestone in the national strike and in Bogotá’s queer culture, demonstrating that LGBTQIA+ people actively defend our lives, using our own cultural codes and practices in protest, despite discomfort from those who prefer we remain secluded and vulnerable in the shadows.

In Bogotá, the Ballroom has always flirted with the desire to dream of different worlds where our existence is not permanently at risk. This environment of resistance and rebellion helps us comprehend how the experiences of the various bodies we inhabit shape the way we, as mariconas (queer), interpret and respond to the things that affect us and belong to us and how we incorporate this understanding into our artistic practices, our identity formation, and the social movements that we build from the ground.

In a conversation with Pantera, DJ, vogue dancer, and singer from Casa de Güirchas, she describes the Ballroom scene in Bogotá as a subversive, hybrid, and capricious culture that draws inspiration from a multitude of aesthetic references for the bizarre and underrepresented identities to be celebrated and heard. However, as she constantly remarks, it is important that it not forget its origins because, although some people find it hard to recognize, Ballroom is, first and foremost, Black.

A Local Ballroom is Possible

Although some aspects of Ballroom culture may remain consistent, in Bogotá there is definitely room for flexibility. For instance, interpreting elements of voguing as demanded by the sonorities and vibrations of local rhythms, there is a connection with another shared past marked by coloniality, as well as with the magic and creativity of us who experience the world from the South.

In this Instagram post, one of the ball participants wears a sexy outfit made from traditional crochet fabric with the colors of the LGBTQIA+ flag and the trans flag during La Bola: Abya Ayala kiki ball.

As proof of this, at La Bola: Avya Ayala, a kiki ball convened by Casa de Güirchas, we saw an aesthetic and sonic proposal that claimed the place of enunciation, territoriality, queerness, and the ancestral ethnocultural legacy with categories such as rara hijueputa (f*cking weirdo), reguerito de guambitos (bunch of little kids), and sincronización de geta (lipsync). This is evidence of a political and conceptual interest in exalting the beauty in the popular, in the rareness of the eccentric local fauna.

It is precisely in these scenarios of experimentation where the crossings of voguing beat with more local rhythms such as neo perreo, guaracha (Colombian electronic music), salsa, or merengue occur, resulting in innovative sounds. These are also mixed with house, afrobeats,6 and funk carioca. These reconfigurations of rhythm invite bodies to move differently with each sonority, to resolve the elements of voguing at a different tempo, to use traditional steps from other genres, to think outside the mold, and to perfume them with the sensuality of a bolero or the agility of a tambora (traditional drum).

This collage portrays some of the incredible people from the Ballroom community in Bogotá as they participate in an open practice session at El Renacimiento, a public park that local voguers have embraced as a space for learning and honoring their skills. Gorgeous Bogota’s mountains are featured in the background.

The way our bodies move to Latin rhythms does not go unnoticed. When we enjoy music with such passion, it’s hard not to feel a sense of joy that’s almost electric, a disruption, and an impossible revelation of ecstasy from the mariquita excluded from traditional family parties. This syncretism becomes a technology of joy that leads us unequivocally to the celebration of our lives in a transvestite oasis among the mountains.

This non-conformist characteristic speaks of a mutant and critical scene that is not only against sound and corporeality, but also against other types of systemic violence that cross our existences inside and outside the Ballroom scene, such as racism, transphobia, gender binarism, misogyny, and classism. Undoubtedly, being a spectator or participant of a kiki ball, training or simply watching, we understand that it is clear that in Ballroom not everything is said, and that our specific context and identities force us to, at least, question and debate the rules and categories of the gringo7 Ballroom scene, creating new ways of understanding ourselves and our unclassifiable style.

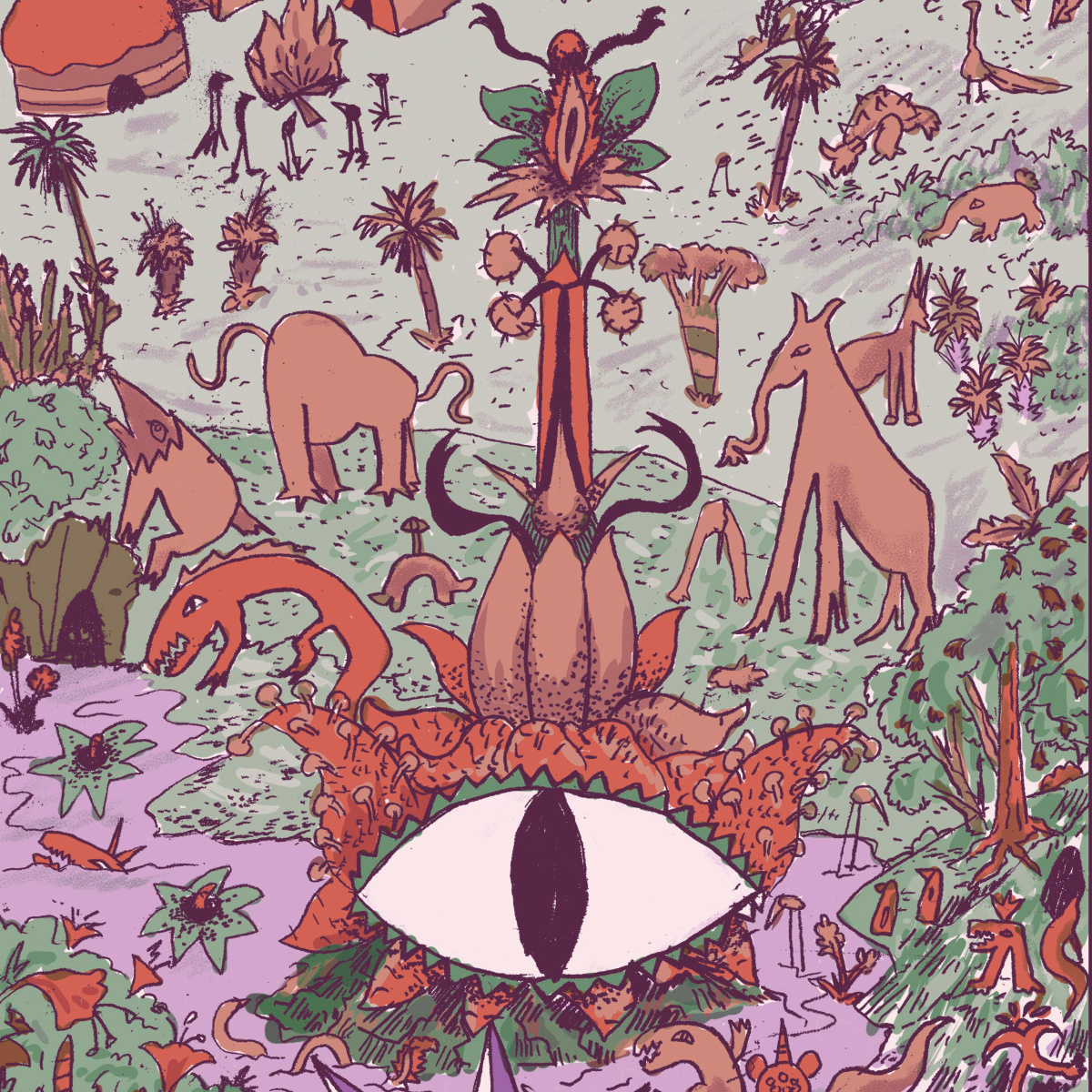

Additional information on the title image: «El infierno» presents an alternative to the punishment of eternal fire for our sins. In this dream universe, transvestites, weirdos, and deviants reign to judge the executioners of morality who in life tormented us with the tragedy of their poor lives deprived of enjoyment.

- 1. «Vogue», or «voguing», is a highly stylized, modern house dance that evolved out of the Harlem «Ballroom» scene of the 1980s. The Ballroom scene (also known as the Ballroom community, Ballroom culture, or just Ballroom) is an African-American and Latino underground LGBTQIA+ subculture.

- 2. When we speak of maricas, mariconas, mariquitas, and all its variations, we refer with affection to all people who are part of the sexual and gender dissidence, not exclusively homosexual men, as it is usually understood. For us, «queer» is a verb and adjective, re-appropriated from discriminatory language to enunciate that sensation, action, or emotion of having fun together using the codes that for so long have been reproached for being an unequivocal sign of «abnormality»: the shameless mannerism, the celebration inserted in the body of existing proudly outside the norm.

- 3. Before Law 100 of 1980, there was the first Colombian penal code dating back to 1837, which considered any sexual/affective approach between persons of the same sex as abuse and was punishable by three to six years in prison. If both persons accepted their consensual participation, both were prosecuted, considering their acts as transgressors of the norm (Caribe Afirmativo 2021).

- 4. «Kiki houses» and «kiki balls» refer to events and houses (chosen families of queer people) that celebrate the Ballroom scene, outside the main houses of New York. Not every house outside the U.S. Ballroom scene chooses to identify as «kiki», since it may imply that they are not as relevant as U.S. houses.

- 5. According to the monitoring of the Convivencia y Seguridad Ciudadana line, at least 80 homicides occurred during the mobilizations of 2021, of which 44 were allegedly committed by the police (Fundación Paz y Reconciliación 2022).

- 6. Afrobeats (distinct from afrobeat or afroswing) is an umbrella term that encompasses popular music originating from West Africa and its diaspora, which began to develop in Nigeria, Ghana, and the U.K. during the 2000s and 2010s.

- 7. From the United States.

List of References

Take a deep dive into the Ballroom scene in Bogotá using the links below

This essay is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Bogotá», curated and edited by Luisa Uribe.

Biography

Vera Fonseca is a trans woman, visual artist, and sociologist from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá, Colombia. Currently, she works as a university professor at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Universidad Nacional de Colombia, alternating her activities with the creation of graphic works in serigraphy and social research, and directing the workshop house Diez Letras Serigrafía. Throughout her professional career, she has specialized in serialized graphics, designing collaborative creation strategies, and researching festive cultures. Among her research topics, her work on the Picotera Graphics of the Colombian Caribbean, Euphoria at the Petronio Alvarez Festival, and artistic and cultural practices of drag art in Bogotá stand out. As a result, she has developed an extensive production of posters, fanzines, murals, and creation laboratories related to her areas of interest. Follow her on Instagram here and here.

Biography

Diana Santos is a sociologist with experience in researching the artistic and cultural practices of individuals with non-hegemonic sexual orientations and gender identities, and their connection to political and community resistance. In 2018, she created the virtual platform ABC del Arte Drag y Transformista, which explores the history and key figures of drag art in Bogotá. Follow her on Instagram here and here.

Published on August 22, 2024

Last updated on February 12, 2025

Topics

From hypersexualised dance culture in baile funk to the empowering body culture in queer lifestyles.

From Bangladeshi electronica to global «black midi» micro scenes.

From breakdance in Baghdad, the rebel dance pantsula in South Africa to the role of intoxications in club music: Dance can be a form a self-expression or self-loosing.

Queer is a verb, not a noun. Thinking & acting queerly is to think across boundaries, beyond what is deemed to be normal.

From linguistic violence in grime, physical violence against artists at the Turkish Gezi protests, and violence propagation in South African gangster rap.

Special

Snap