Malikah Raps out of Rage

The Lebanese musician Malikah started to rap out of rage. As a central figure in Arab hip hop she now literally travels between different worlds: from the streets of Beirut to Europe’s avant-garde concert halls. Norient caught up with her in Berlin to talk about her musical roots and sense of belonging in an English-speaking and male-dominated hip hop scene.

Malikah was the first female rap star to emerge from the young hip hop scene of Beirut. Born as Lynn Fattouh in France, the daughter of an Algerian mother and a Lebanese father, she grew up in Lebanon. She started to rap in English and French, and then, in 2006, switched to Arabic while reinventing herself as Malikah («Queen»), a title she's kept ever since. Apart from appearing on jams and collaborations in the Arab rap scene, Malikah made her way into the international festival circuit with projects such as Lyrical Rose, her trio with Kenyan artist Nazzi and fellow rapper Diana Avella from Columbia. She took part in different versions of Damon Albarn's Africa Express where she also met André de Ridder, conductor of the experimental ensemble Stargaze Orchestra. This year, de Ridder invited her to perform alongside French-Malian rapper Inna Modja as a part of the Stargaze project «Spitting Chamber Music» in Berlin and Cologne in May 2017.

[Eric Mandel]: When did you pick up a microphone?

[Malikah]: I never thought that I could rap because there was no Arabic hip hop per se back then. And as funny as it sounds, when you don't have people who have opened the door yet, when you don't see somebody doing it, it was not an option. Only American people or French people could rap, and we couldn't. Until one day I remember I bumped into these two guys in a little bar, rapping. I realized I could do rap, too, and I was so excited that I went to them directly and told them that I wanted to rap with them. And that is where the whole journey started.

[EM]: How did you make your own version in Arabic?

[M]: Well, I started in English. I used to make fun of people who rapped in Arabic. «What are you doing, rapping in Arabic, it’s not a language for hip hop!» (laughs). For five years I rapped in English, until the war happened between Lebanon and Israel. This is when I switched to Arabic, and this was when Malikah was born.

[EM]: Why was the war decisive?

[M]: It was the first war I had experienced. It hit me so hard that I wanted to write a song for the Lebanese people. I started to write in English, but then I discovered that I had an inferiority complex because I came from a colonized country. I thought that English and French were better than my language. I started to think: Why would I choose to communicate with my people in another language than my own? Why would I think that Arabic is not good enough? It's a beautiful language! That's when I decided to switch to Arabic, and I wrote my first Arabic song: «Ya lubnan».

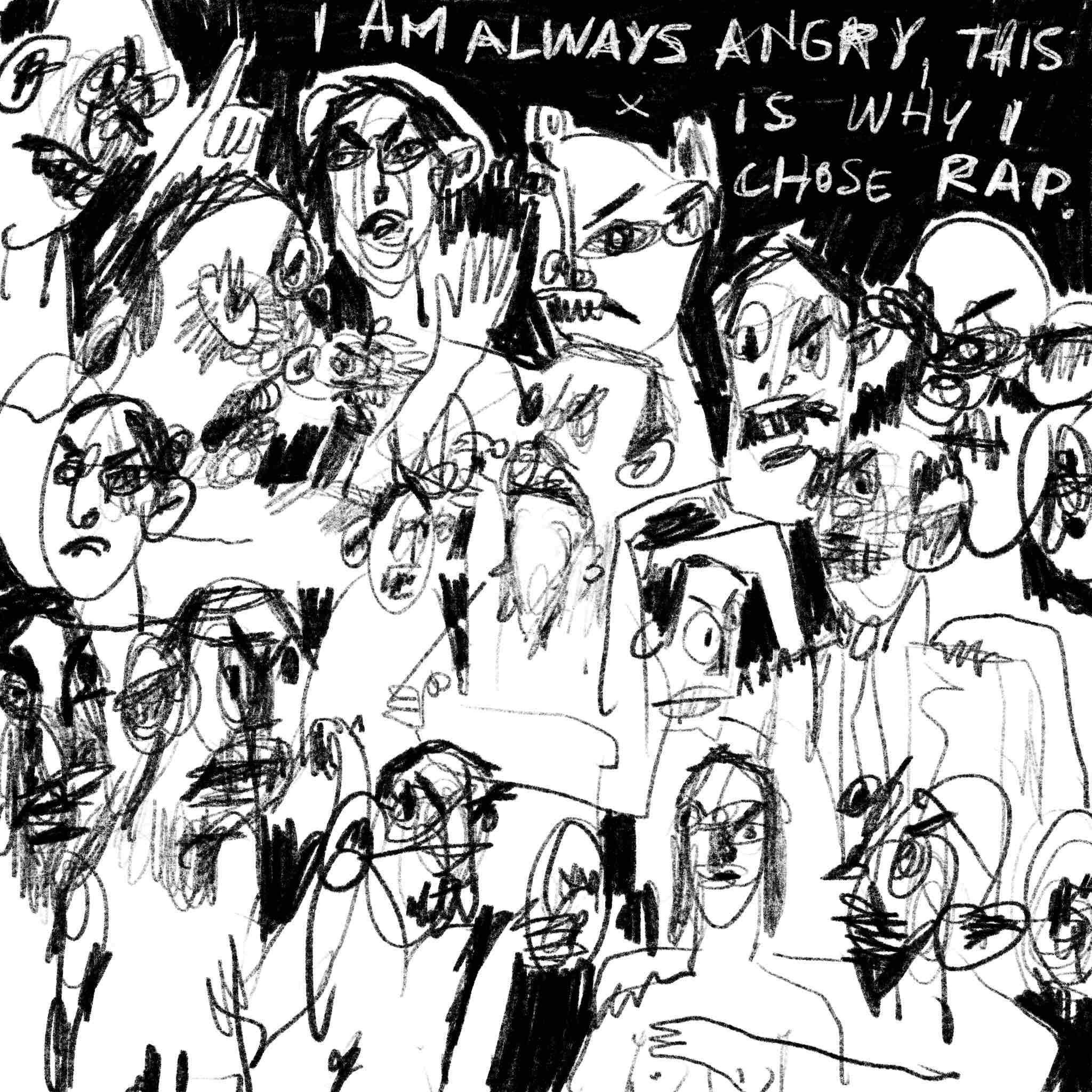

Being Angry

[EM]: My first contact with your music was the song «Intikhabeit 2009» on the Golden Beirut compilation (released by Norient and Outhere Records) and my first impression was that anger really is your energy.

[M]: Of course (laughs), I am always angry. This is why I chose rap. I felt that coming from a country like Lebanon, where you feel oppressed, and there is so much injustice, you are feeling that nobody is listening to you. You find yourself in a place where there is mostly anger.

[EM]: While you were developing your style, rap in itself became very important in Lebanon, Tunisia, and Egypt. How did you experience these formative years?

[M]: The period of 2004 to 2007 was when Myspace happened. Internet became also much more present in Arabic countries, and this is when Arabic hip hop really stood up, when it was really born. Of course, in Lebanon, we always had a scene. We are considered the Boogie Down of Arabic hip hop, the Bronx. We were there, doing our thing, but obviously we didn’t have studios to do that, and we didn’t know that people were doing it in Egypt or in Palestine, too.

[EM]: While musicians from Arab countries making techno, house or even experimental music all aim primarily at the European or American Market, hip hop appeared to be the quickest to connect and develop independent structures.

[M]: Because it is part of our culture. In hip hop we are all about connecting and being open and embracing the other. We all think like that, that we are all equal, and that we should be loyal to each other, we should be united.

Obstacle or Plus?

[EM]: How did you come together with the Stargaze Orchestra?

[M]: I met [conductor] André de Ridder at the concert of Africa Express. It is organized by Damon Albarn and a lot of other amazing people. I have been doing it with them for years now, and I am always waiting for it the whole year. They invite about 30 artists, musicians, singers, rappers, from Africa mostly, and a few from the UK. We all meet in one big space and you go from room to room, where we are just jamming the whole day. The next day we have to perform these new songs in a five hour concert. It's crazy, and beautiful.

[EM]: How hard do you feel that even in hip hop, you are operating in a male-dominated world? How did you earn your royal status?

[M]: (smirks) Much easier than you think.

[EM]: Because as a woman you are special?

[M]: Yeah, thank god, I am blessed. But I was also strong enough. I've always had a tough personality. Even before I was rapping, I have never been intimidated by men, never felt I was different. I always spoke my mind, always fought for what I wanted, always wanted to beat everybody in sports. So I really already had the personality of a rapper before I was a rapper. I agree with you that it is hard, as everywhere in the world, there are very few female rappers. The same applies to us. And yes, I get more listeners hating at me. The fact that I am a woman opened a lot of opportunities to me, but it is because I am a woman who is this strong. So what could have been an obstacle became a big plus.

Biography

Links

Published on May 31, 2017

Last updated on September 14, 2021

Topics

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

From Beyoncés colonial stagings in mainstream pop to the ethical problems of Western people «documenting» non-Western cultures.

Why is a female Black Brazilian MC from a favela frightening the middle class? Is the reggaeton dance «perreo» misogynist or a symbol of female empowerment?

How does Syrian death metal sound in the midst of the civil war? Where is the border between political aesthetization and inappropriate exploitation of death?

Snap