A Heavy Element of Escapism

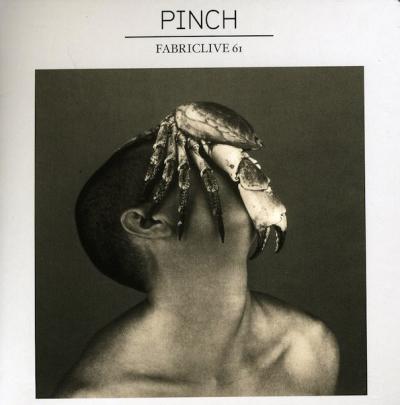

Dubstep’s philosopher Rob Ellis aka Pinch from Bristol keeps alive the sound of early dubstep-days. In his mind, the tempo, the dark bass-lines and the meditative energy of the genre risen in south London create vibes of embryonal well-being. In the interview the producer and founder of the label Tectonic also speaks about patience and pressure in dance music.

Complete darkness. A haunting sub bass makes my body. Even my viscera vibrate intensely. When I began to visit the FWD >> club night at Plastic People on a regular basis in 2011, I was immediately intrigued by the fact how little the traditional dubstep sound has lost its fascination. This music still provides a space, where the visual is secondary and the immersion in sound gets a new relevance. In this context, dubstep is also a rejection of the sensory overload of everyday life.

Although the sombre half step sound from the likes of Youngsta is still an unique listening experience, there is little musical innovation. The other extreme is the mainstream-step of people like Skrillex, in which reticent silence is replaced by the loudness of war and relaxed vibes are confused with gorilla posturing. An interesting remedy is coming from artists for whom dubstep is rather a philosophy than a style. One of those producers, who have never given up the constant pursuit of creative progress, is Rob Ellis aka Pinch.

His label Tectonic is a refuge for some of the most innovative bass music releases, which the recent albums of Author, Pursuit Groove or the recent Distal shows. When Pinch released his full album with Shackleton last year, it not only felt really exceptional because it was released very suddenly, without any immediate notice. It was also one of the musical surprises of 2011 where Pinch´s soundtrack-like atmospheres and Shackleton‘s otherworldly percussion orgies amalgamated into a beautiful work of art. Since the mid-2000s, their sound has always pursued new musical crossings, which would never have been possible without the main artery: dubstep. But what is dubstep nowadays anyway? Sometimes it is worth to look briefly in the past.

His Fabric mix is able to transport visceral sub-basses and the meditative feeling of dread in the present, where the attention span, especially for music, has become a rare good. I met Rob in a café in London’s Farringdon, in which he indulged in one of these English breakfast plates, which make lunch and even dinner obsolete. When the Bristol-based artist had played his set on the previous night at his release party at Fabric, he proved once again that the quality of his music lies mainly in his eclectic approach on dance music and the intensity of sound that permeates the body. While pursuing musical innovation by making excursions in techno and house, Pinch has remained faithful to the original values of dubstep, such as the love of dubplate culture. «Because of the better sound», as he explained, he did press some acetates especially for his gig.

[Philipp Rhensius]: How did you actually come to dubstep?

[Pinch]: When I went to FWD for the first time, around late 2003, I knew I want to bring it to Bristol. I immediately felt that it was something that could work in Bristol. Dubstep was something different, it was exciting. At the time I was mixing bits of garage and grime with techno and random electronica – having got bored with Drum & Bass scene. Kode 9 at FWD was enough for me to turn my attention completely to dubstep. I started a night called Context in January 2004 and began bringing up London DJs and producers to Bristol – people like Loefah, Vex’d, Distance, Cyrus.

[PR]: Especially the classic UK dubstep has this interesting tempo mode. There is a deceptive slowness, behind which an enormous energy is concealed. I always wondered what was actually happening on the dance floor at the first nights. Did the people just stand around?

[P]: [laughs] Well, standing around nodding to the tunes was a big part of those early nights! But yeah, I've got some specific memories of playing abroad – the first few times when sometimes people didn't know how to react to the music and how to dance to it. You had these situations when people were kind of looking around at each other, a little confused. Often around half way through the set people would just suddenly get it and then it was like: «alright, yeah, it doesn't matter how you dance to it.» For me, I really liked this of challenge of «activating» the dancefloor. I always thought I was doing a good job and when you got people dancing from a standstill – it was really great. It was like: «Yeah, I've kind of changed the way the people think about this music.»

[PR]: Did you use certain tracks to attract a lame crowd?

[P]: Yeah, sometimes it was tunes like Loefah's «I» remix or “System”, or early Skream stuff like «808 Dub». But it wasn't necessarily a particular tune, it was more about building a certain momentum. Sometimes it was the tune after a big one that would create the switch point – it just meant people had started connecting with the music and letting go of being self-conscious.

[PR]: Speaking of switchpoints… What do you think of the current development of dubstep?

[P]: Musically I don't generally like the majority of what falls under the term dubstep these days. At first I was kind of resistant to the more aggressive stuff and it annoyed me that it became representative of the genre to most people because for me, this midrange sound wasn't really what this music was initially about – it was rooted in something more cinematic. But I've come to accept that it's impossible to hold on to something like that period of time forever. What happened in 2004 and 2005 was a very special time and you can't hold on to these times because the circumstances changed. It's never going to sound fresh forever. There was a certain time when you had this kind of energy flash, there was a lot of genuine excitement. At the time no one was being driven by financial motivation because there wasn’t any money in it. Everyone was cutting dubplates to DJ with and paid for it from their own pockets. A few years ago it bothered me how the dubstep scene was changing and shaping up but I’ve long stopped worrying about all that – what´s more important is making the effort to keep things interesting in things that are relevant to me.

[PR]: I think your Fabric mix is a good sign for this development. It's like a succeeded continuation of dubstep. It's like looking forward while staying faithful to a certain sound of the old days. It contains a lot of dissonant and spatial sounds that even appear in some 4 on the floor tracks.

[P]: I wanted to include a selection of tunes I have been making and feeling recently, not just a straight dubstep selection even if most people might only know me for my dubstep productions. You’ve got to follow your heart and trust your instincts. I've always believed at the end of the day the first person that you have to impress, especially when it comes to making tunes in the studio – is yourself. If you genuinely like it – chances are someone else will too!

[PR]: It's interesting that you are sticking to these deep and dark atmospheres…

[P]: Well, I found this darkness would give me space to let my head drift off. It's like a meditation or whatever you want to call it. There's a genuinely sort of meditative quality about that early sort of dubstep. I used to find that it was dark music but it would make me feel so happy listening to it, very genuinely so. But I think what is often forgotten are the people in the dance themselves. They are absolutely essential for the atmosphere conducive to a good experience. Around 2004-5, dubstep was such a small underground scene and it wasn't even considered like a cool thing as such. But the people who were there, were there because they were bored with other music scenes and they were looking for something different – they had open minds. Having like-minded people gather like that brings a certain, special energy to the dance.

[PR]: What exactly triggers this meditative effect? Whenever I read the expression «eyes down» I think it would describe the atmosphere quite well. It is actually a very different feeling compared to house or techno nights.

[P]: Completely, yeah. Well, not completely. You can get into some very interesting head spaces with good techno as well. But I guess the difference is the level of the energy that comes from the drums and I think with early dubstep it was much easier to dance on the half-step. It was like 70bpm rather than 140bpm. Because 140 really gets your heart going, it's like high energy techno. What's important here is that as a raver you can switch between the half-step 70bpm and the full 140bpm pace. Half-step beats can have the energy of 140bpm if, for example, the bass line suggests the faster pace over slower beats. The result is that you can switch between this lazy skank-y kind of thing and a full speed, heart racing tempo. When DMZ has started, it was the first full night rave until 6 in the morning. That was when dubstep became something a bit different. FWD was on a Thursday night and people would go to work on a friday. I realised that dubstep was in many ways the perfect kind of music for someone who didn't necessarily want to take a bag of pills to go raving or whatever. You could just dance to it all night without exhausting yourself like you would do with drum&bass and it was just a real nice tempo to get a kind of long stamina momentum. FWD was more of an urban geeks music appreciation society than a rave as such – DMZ changed that.

[PR]: Do you have these specific situations in mind, when you are producing?

[P]: It depends on the mood I'm in really. More often than not I just sit down and play around with sounds until something comes out that I like but sometimes I do have this sort of idea of what I want to do. Like I decide I want to make a house tune, but a house tune that has a ’95 Metalheadz vibe to it. I kind of like to have the atmosphere of the early dubstep days and move it into some new environment. That’s how «Croydon House» started actually!

[PR]: What do you think about the progress in dance music in general?

[P]: There is a heavy element of escapism that has driven the development of dance music. If you're looking for escapist music then you can't really escape from the familiar. When a new genre of dance music emerges, as dubstep did, the opportunity to hear it is very restricted at first – in the early days you could only really hear dubstep at FWD and a little on Rinse FM – so it felt very special and out of the ordinary. And as soon as something is becoming the familiar it's getting boring. Once you get to a point where it's being played on the radio all the time, TV adverts and so on – it becomes part of the everyday life and then it loses the power to provide such an escapist context.

[PR]: Bass in general does have an escapist force. How would you describe your relationship with bass?

[P]: I enjoy the physical sensation of good dance music. It's supposed to arouse your very primal instincts as a human being. I mean, pretty much the only time in nature to experience extreme subbass otherwise is in extreme situations, like earthquakes, thunders, these kind of dramatic events. Situations that make you alert and excited. I have a little theory about «meditative bass« actually. As an embryo in the mother's womb, when the ears and brain are developing, the first sound you hear is bass as it is all that properly travels through the protective, embryonic fluids. And while you're an embryo you are in perfect harmony, in total equilibrium with your mother – there is no experience of hunger or any other need. I would get a calm feeling from heavy bass-y dubstep sessions and it made me wonder if perhaps there’s an underlying subconscious connection between sub bass and this time of being in harmony with your mother as a growing embryo.

[PR]: Besides the Fabric mix you did an amazing album with Shackleton, which sounds quite different from your previous work. How did this extraordinary collaboration come about?

[P]: I've known Sam for years and I guess it all started when he was in the UK. He stayed at mine for a few days and we decided to make some music – we were thinking – maybe do a single. I think he came up to Bristol two times and I went up to Berlin for a few weeks. We spent about probably 7 or 8 days in the studio there and we just got so much done in that time until we thought it's kind of enough for an album so we just carried on working on it. It was quite easy to work together. I think we complemented each other well in terms of knowledge and stuff.

Video not available anymore.

[PR]: Have you sent the tracks back and forth to each other?

[P]: Not really, we did it all together pretty much. Most of the album was done in his studio in Berlin. It was about a year and a half from start to finish.

[PR]: Somehow it seems to be a natural thing that you’ve made an album together. Both of you have similar musical backgrounds and you are always one step ahead of the scene. But I can imagine that it's really hard for two such idiosyncratic producers to work together.

[P]: What I really like about collaborating with someone is that you have to come to a point where you compromise. So there are certain things where I would maybe think: «That’s OK like that» and he would be like: «No, I don´t like this kind of snare» or something like that. And when you find something to replace it that you both agree on – the result is stronger. I really enjoyed making the album with Sam – we had a lot of fun with it.

[PR]: You already played in the states several times. With regards to the development of the American dubstep success, do you think the majority is still able to understand your music?

[P]: I'm kind of lucky. My agent in the states understands very much what I do. He is more a foundation fan and so I never really get booked for these shows. Frankly there are lots of situations in the states where unless you're playing stuff that tears the ceiling off people don't really get it but thankfully I haven’t had to deal with that too much.

[PR]: They might not have enough patience.

[P]: Yeah, exactly, I mean culturally in general people all over the world have less patience for music than they used to have. If it doesn't grab your interest immediately you click on the next thing. Whereas when I grew up I could buy a CD and it was like: «I paid my money for it so I will really listen to it.» Sometimes I didn't get stuff immediately so it took some time. But those were often the albums that changed the way I would think about music. Today, it's so easy to just click on the next thing people run the risk of missing out on something that’s rewarding in a slower or more long term kind of way.

This article was first published on Dummy the 23. May 2012

Biography

Published on July 30, 2012

Last updated on April 02, 2024

Topics

From hypersexualised dance culture in baile funk to the empowering body culture in queer lifestyles.

From breakdance in Baghdad, the rebel dance pantsula in South Africa to the role of intoxications in club music: Dance can be a form a self-expression or self-loosing.

Can a bedroom producer change the world? How do artists operate in undersupplied conditions?

A generative practice that promotes different knowledge. One that listens is never at a distance but always in the middle of the sound heard.