Music as an Exit Strategy

At Jamaicas General Penitentiary, prisoners can join a music-focused rehabilitation program. The award winning documentary Songs of Redemptions is a fascinating portrait about the social power of music. Songs of Redemptions is available worldwide for stream or download at MusicFilmWeb.tv. Co-director Sans talked to Andy Markowitz via Skype from Barcelona about her road to «Redemption».

The Enlightenment poet William Congreve’s famous maxim that «Music has charms to soothe a savage breast» could find no better testing ground than prison. For example, Jail Guitar Doors, the charity founded by Billy Bragg in 2007, has made a significant impact on the lives of many UK inmates by providing instruments and holding songwriting workshops, and was later expanded to the States. In Jamaica – a country not generally known for a progressive penal system – music-focused rehabilitative efforts go back even longer. For more than a decade, residents of Kingston’s notorious Tower Street Adult Correctional Centre, better known as the General Penitentiary, have had access to musical training, a radio station, and recording facilities through a larger education program officials credit with significantly reducing once-rampant violence within the prison’s imposing brick walls.

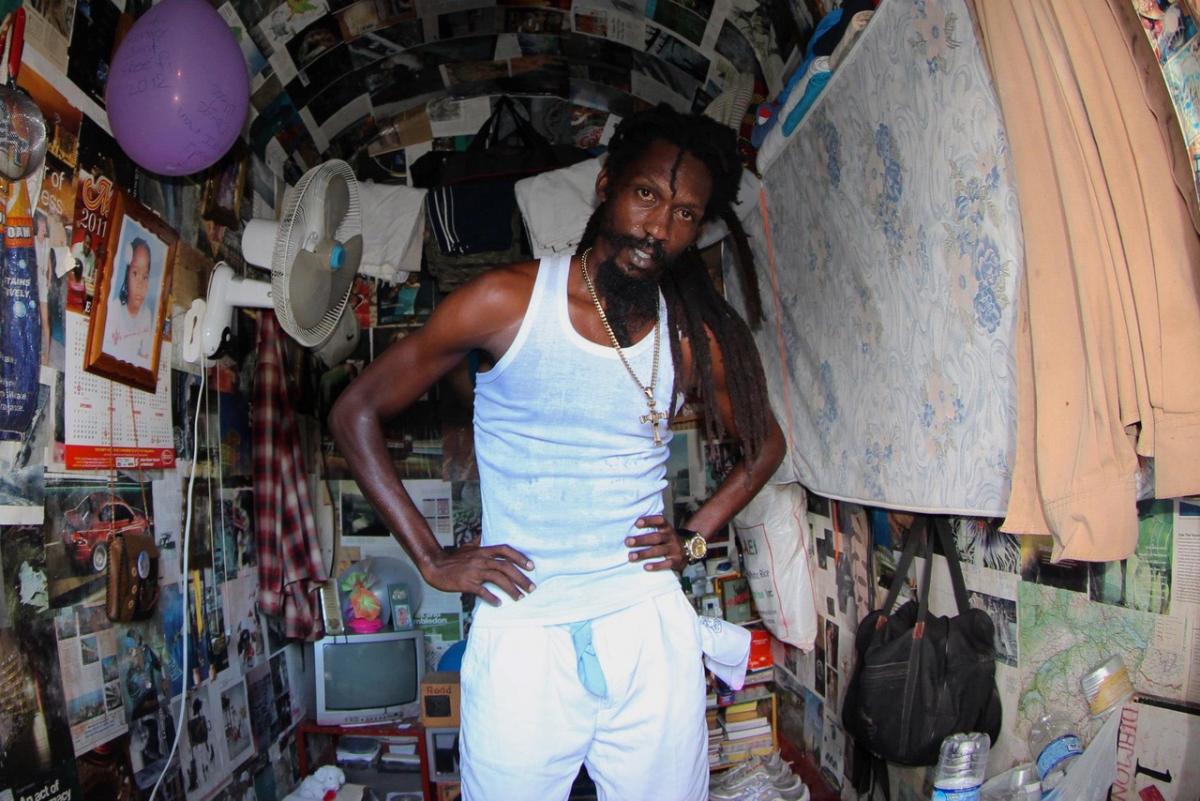

The music documentary Songs of Redemption goes inside «GP» to show how the ability to make music behind bars has affected prisoners’ lives, providing not just a desperately needed creative outlet but also a means to confront their violent pasts, and to send a message of peace to listeners on the outside. Catalonian filmmakers Amanda Sans and Miquel Galofre weave intimate portraits of incarcerated artists like dub poet and lifer Jerome Tucker; Hornsman, a gifted ska trombonist jailed on a gun charge who yearns to resume his music career; Pity More, formerly known as Pity Less and doing 20 years for murder, who pours his regret and newfound faith into impassioned reggae raps; and Serano Walker, a bantam singer-songwriter whose music ranges from dancehall rowdy to achingly tender.

[Andy Markowitz]: How did you end up hanging out in a Jamaican prison?

[Amanda Sans]: [Laughs] I visited Jamaica for the first time in 2008. I was working on a Spanish TV program, it was like a travel program – we were portraying different countries around the world through the stories of Spaniards living abroad. One of the countries we chose was Jamaica, and there I met the executive producer of [Songs of Redemption], Fernando Garcia Guereta. He’s a Spanish guy that has been living in Jamaica for about 15 years. He was one of the main characters of this program. We got along very well, and he started to talk to me about the General Penitentiary, that there was this rehabilitation program going on inside that prison. At that time there was a very famous reggae singer inside GP, Jah Cure. He was found guilty of rape and spent eight years inside the General Penitentiary. He was part of this rehabilitation program. He became famous releasing songs from prison. What he did through this rehabilitation program is he said, «I’m sorry. I made this mistake, I’m a new person». The lyrics of his songs were suddenly very nice and very constructive. There was a before and after with this singer.

Our idea was to do the documentary when Jah Cure was inside, but it took us a long time to get all the permissions to go inside that prison. We’re the first ones, the first cameras, to go inside GP. By the time we got permission, Jah Cure was out already, but we were still interested in the story, especially because Jah Cure’s cellmate was Serano Walker, and he’s a very talented musician. Before we went into GP to film, he released a record. One of his songs was in Fernando’s first film, on the soundtrack.

[AM]: So some of the characters in the film, like Serano, and Andrew, the horn player, had musical backgrounds. Are there people in the film who were not musicians or songwriters until they got involved in this program?

[AS]: Yeah. For instance, Pity More, he was what they call in Jamaica a DJ. He was involved with music but just as a hobby, nothing serious.

[AM]: He had a sound system?

[AS]: Yes. I mean, everyone in Jamaica is involved in music. Jamaica is music. Everyone dances and sings. But really, from our point of view, what we consider people really involved in music, it’s just Serano and Hornsman. Pity More was involved just like any other Jamaican. He went in prison and was involved in this massive forgiveness process, and it turned out that he’s very talented. He has this powerful voice, and he’s a very good songwriter. But he was not doing any of that before prison. He was involved in shit, like all of them – well, you can put that in nice words [laughs]. They all come from what they call the garrisons, which is the ghettos. Most of them were involved in some sort of criminal activities. They all more or less admit that. Some of them don’t admit the crime [they went to prison for], but at least they admit that they were involved in violent activities. The ghetto in Kingston is a really, really hard place. If you want to survive there, you more or less get involved in this type of activity.

[AM]: I wanted to ask you about the discussion of that in the film. Are you familiar with a film that came out a few years ago called Breaking Rocks, about the music rehabilitation program in British prisons that Billy Bragg started?

[AS]: I’ve heard of it, but I haven’t seen it.

[AM]: That film did not go into what its subjects did or were accused of doing. In fact, I asked the filmmaker subsequently what one of them had done and he wouldn’t tell me. Your film went a very different way – you had each of your main characters explain what they’re in for. Was that a choice you wrestled with?

[AS]: I thought it had to be in the film. We deliberately left that for the end of the film – that was a very clear idea we had. We didn’t want that information in the very beginning because we didn’t want the audience to judge them for what they did. This is more about a rehabilitation process. But I think it’s interesting to know what they did. All these characters, they have different stories but they have one thing in common: they come from very poor areas and they grew up with violence. Serano is telling you that he never met his mother and never saw a picture of his mother because somebody [killed] his mother. He was raised in a ghetto surrounded by violence. Pity More is telling you that he had a father that was beating him and soaking him in water with salt and pepper. I’m not justifying them at all – they did the crime, they deserve their sentence. There are people that are also growing up in the ghettos and are not committing those crimes. But I think that violence is a very worrying thing in Jamaica that is affecting a lot of the youth in Jamaica. I thought that information had to be there.

[AM]: It’s also a way of showing how far they’d come, and how music has been a catalyst for putting them on that road.

[AS]: I spent many months inside GP and I can tell you that music is really the only thing that is releasing them from that stress. You cannot really see GP, how it is, 100 percent, because we had limited access to the prison. We only could shoot in the cells for one single person, which is what you see in the film. There are cells for five people, and people sleeping with hammocks. I was not able to show that.

[AM]: Those were conditions for you to get permission from the prison officials to do this?

[AS]: No, the only condition was to talk specifically about the rehabilitation program, nothing else. So anything in the film should be related to the rehab program. We had the condition that these characters had to be related to music and rehabilitation. We could not choose someone else.

[AM]: Were the prison officials eager and cooperative as long as the focus was to showcase this program?

[AS]: Yeah, it was quite OK. We could more or less film what we wanted. There was always a warden with us, for security reasons. Especially because I was a woman. But if we were respecting the conditions, we had quite a lot of freedom.

[AM]: Were there ever times where you felt threatened?

[AS]: Not at all. I didn’t feel really comfortable for the first week, because I am a woman and there are 1,800 guys there who had no access to women, and they are not used to seeing a woman around. I had all those eyes on me. That’s one thing. The second thing, I was a director, a female director, which is something they don’t really understand, because they are quite sexist. I co-directed the film with Miquel, and when I had any requests we had to do it through Miquel. Wardens, they didn’t understand that a woman was directing. But then they got used to me, and at the very end they were not paying any attention to me. I didn’t feel in danger. It’s quite calm in there, compared to how it was years ago.

[AM]: Was it hard to get the prisoners to trust you and to open up about their lives? Is that somewhere where perhaps being a woman helped?

[AS]: I think being a woman helped. That’s something we talked about with Nando, the producer, and Miquel, the co-director. All of the characters lack a mother presence in their lives. I used that when I interviewed them. And it was not difficult to make them talk. Some of them have been there 20 years, and no one’s paying attention to them. For the first time somebody’s asking them, «Who are you? What are your dreams? What are you doing? Let me hear your songs». They were really, really open to talk. In Jamaica, society and the government treat people in prison like rats. The film has had a very nice impact in Jamaica. I think we created a debate about second chances – you’re a prisoner but you have the right to learn a skill or reinvent yourself.

[AM]: Do you think this program will help some of those who are lifers get an opportunity to get out, to get parole?

[AS]: I have no idea. I thought about that too, especially in the case of Serano, but I don’t know. I know that the Jamaican system of justice has a lot to learn yet.

[AM]: It’s funny that this grew out of a show about people living in beautiful, exotic places abroad, and you go from that into this prison story. Is your next project going to be something more light and fun?

[AS]: That was exactly what I wanted, but I can’t manage to escape from Jamaica. I’ve been back two or three times since I did Songs of Redemption. I had to go back and shoot for an NGO that was working in GP – they started yoga classes. I enjoyed that a lot, because I do yoga too. And I’ve shot another documentary, with Miquel too, about parenting in Jamaica – how the concept of family that barely exists in Jamaica is causing all this violence and all these problems in society. So it’s not a happy issue either. I’m in love with Jamaica and there are so many stories there, but my next project I’d like to change a little bit [from] the drama thing [laughs].

This article has been first published on music documentary magazine MusicFilmWeb.com.

Biography

Published on December 09, 2016

Last updated on August 24, 2020

Topics

How do musicians fill or widen the gap of feeling at home in a world that is radically unhomely?

Can a bedroom producer change the world? How do artists operate in undersupplied conditions?

Loneliness can feel like isolation, but can also be a positive solitude by keeping distance from the worlds’ chaos.

From linguistic violence in grime, physical violence against artists at the Turkish Gezi protests, and violence propagation in South African gangster rap.

Snap