A Disenchanting Encounter

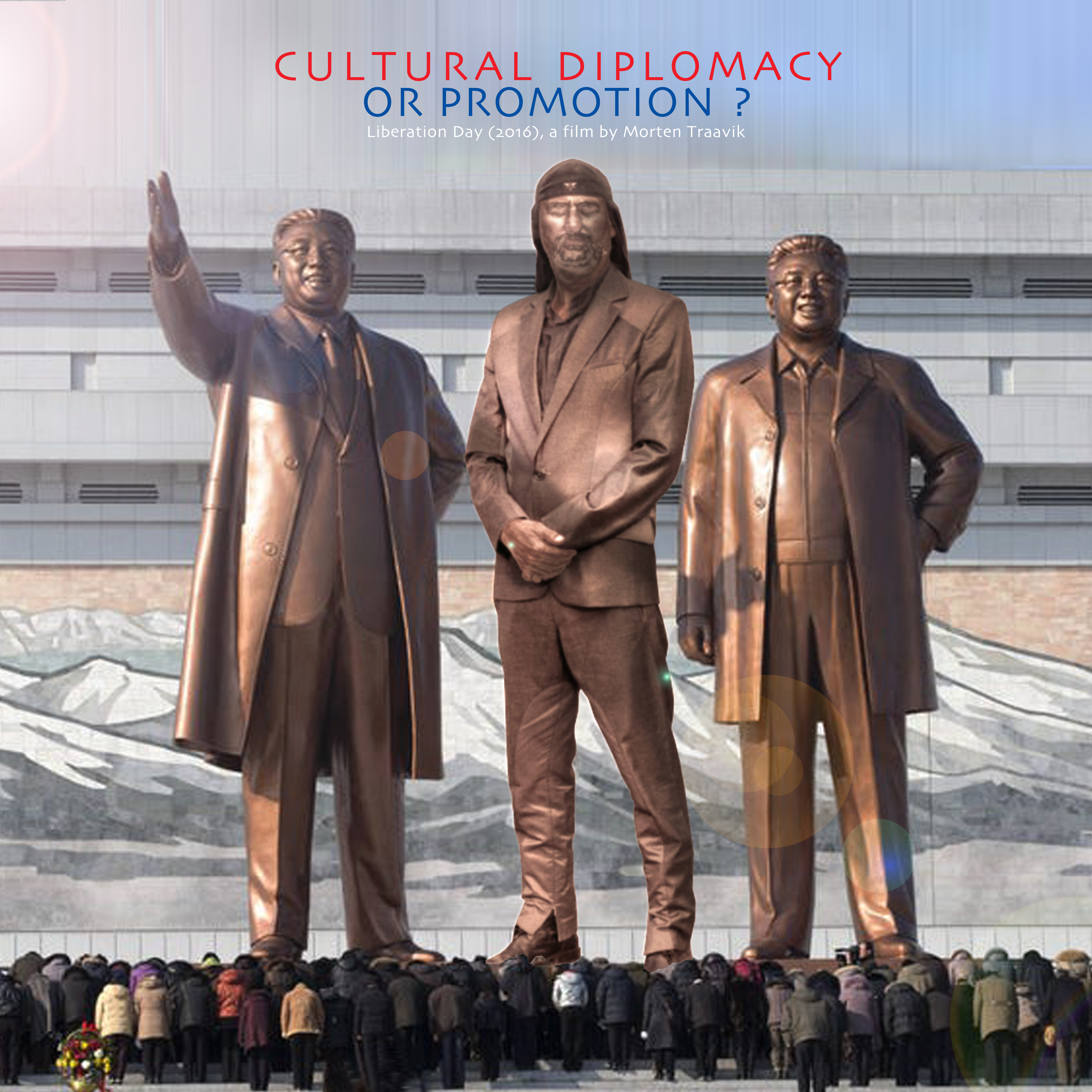

The Slovenian cult band Laibach has been invited to perform in North Korea as part of the celebration of the National Liberation Day. Is this tour cultural diplomacy in the traditional sense? Or promotion? And if yes, for whom? Historian Friedemann Pestel takes a critical look at the movie Liberation Day and on the ambivalent role of its director Morten Traavik.

In 2015, Laibach’s visit to North Korea was a sensation; it marked the first appearance of a foreign rock band in one of the most isolated countries of the world, a communist state that few people from outside have actually seen. At first, this event seems like another case of a cultural encounter between the West and the East, between a democracy and a people’s republic, between the capitalist and the communist world, a promotion of artistic freedom and self-expression.

Is Laibach in Pyongyang, therefore, just a new sort of cultural diplomacy? In the field of classical music, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra visited the Soviet Union in 1959, the Berlin Philharmonic in China in 1979, or the New York Philharmonic again in North Korea as recent as in 2008 (the latter performed the folk song Arirang, just as Laibach did seven years later). Traditionally, such visits involve planning and negotiations between public and private representatives of both countries, and were seen from both sides as part of international cultural relations.

A One-Sided Relationship

In the case of Laibach, the political involvement was rather one-sided. The North Korean regime invited the band for the 70th anniversary of Korean independence from Japan, of which Korea had been a colony since 1910. But there was no Slovenian participation aside from the band's appearance – Slovenian officials even refrained from attending the concert, let alone promoted the project. As for Laibach, they remained quite silent on their motivations, and they seemed to represent themselves and their own controversial image rather than a national regime, ideology, or value system. This image, in return, seemed to «echo», in Slavoj Žižek’s terms, the self-representation of the North Korean regime.

Yet, this was precisely where mutual disenchantment began: The North Korean officials quickly discovered that Laibach’s symbolism was too ambiguous to fit into the regime’s antifascist ideology (whereas their own cult of leadership and mass spectacles hardly impressed the foreign visitors). Instead, if Laibach actually did convey a message of propaganda, it was entirely for their own branding, and collided with their individualism. Their understanding of «propaganda» seemingly owed more to the older roots of the term in advertisement and promotion than to ideological instrumentalization - the somehow anachronistic representation of the North Korean regime, in European eyes, turned into a stage set for a commercialised performance pattern that had already been proven successful at a global scale.

Subversion Never Got a Chance

During the band's visit to North Korea, there was also little opportunity for playful political subversion. If Laibach ever expected to play on an ambivalent register by putting their own authoritarian visual aesthetics in relation to North Korean state propaganda, this idea was quickly pulverised by the harsh realities of bureaucracy and logistics. The documentary shows how lacking screens and cables, censorship, and a mock audience for the dress rehearsal left little room for irony or ambiguity – very much, one might argue, to the disappointment of Western democratic viewing expectations.

During the concert, the camera – a bit too ostensibly for Laibach’s international fame – looked for signs of emancipation or conversion in the faces of the audience. Instead, the reactions captured suggest a more complex relationship between performers and listeners largely sticking to their trodden patterns of reception – voluntarily or not. The party rally applause Laibach received at the end might have – or not – disillusioned the band; it certainly disabuses the film audience about the immediate effects of cultural diplomacy.

An Arranged Affair

We might, therefore, provocatively ask whether Laibach in North Korea was not, all in all, a lukewarm event, with domesticated reactions on both sides and a spirit of compromise that, in the outcome, offended no party involved. Before coming to such conclusions, we might yet try another approach to the film by looking beyond the two sides involved – Laibach and their North Korean hosts. We might ask some questions about a «third» instance that played a decisive role in getting them involved: Why was the visit of the band in the world’s most isolated regime, one that attempts to fully control its image to the outside, so well documented by a film crew? The end credits are given to North Korean foreign embassies and to Norwegian and Latvian public film funding agencies: What do they tell us about the cultural and diplomatic relations behind?

What part did the film’s co-director play? Especially considering that at the same time he had the role of the official leader of the foreign delegation, well-experienced in dealing with the authoritarian authorities, and included having to make artistic and political compromises on behalf of the band. To what extend could a documentary be independent or neutral given the control of artistic performance in North Korea that includes music as well as film?

The Director as Impresario

This film is not only a film about the ambivalence of attraction and misunderstanding between a group of artists and a political regime, but also about an impresario figure with his own professional agenda: on the one hand, a frequent visitor and long-term collaborator with the North Korean regime in artistic matters; on the other hand, a business relation with Laibach as their «director» in more than one sense in North Korea, but also as a co-creator of their visual aesthetics in videoclips. As Laibach and North Korea regularly raise attention independently from each other, their combined promotion promised to be a commercial success.

Towards his partners, the impresario may have understood himself as a cultural and commercial broker rather than a political actor. He may have seen his job as that of setting up an artistic performance, and not a political demonstration. He may have «culturalised» ideological divergences into questions of «respect» or «communication» when dealing with reluctant North Korean officials. He may have considered his work as a commitment to the parties involved or as neutral intermediation. But the spectators of the film may also consider his role as another layer of ambivalence in a complex setting of artistic production. This key makes the film even more thought-provoking and debatable in the best sense of the term.

Biography

Published on January 02, 2019

Last updated on April 11, 2024

Topics

Can a small chinese radio show about Uyghur music stand against the censorshop of the Communist Party of China? Are art residencies useful?

What happens when U.S.-blogger collects african music and offers it for free? What is the difference between «textually signaled» and «textually unsignaled»?

Snap