Grime Instrumentals and War Dubs

Things have grown quiet around UK based Grime in recent years. Now noisy, power- and playful instrumental Grime tracks keep reaching us again via online platforms and newsletters. London based producer Footsie tells us via phone how he sees the scene right now. He foresees a new wave of amazing grime tracks. Enjoy some of them in this post.

[Thomas Burkhalter]: Hi Footsie, Where do I reach you?

[Footsie]: Right now, I’m at home checking emails, and sending over some files.

[TB]: You released the «King Original Series» recently, four CDs with instrumental tracks. Why do we keep hearing so much instrumental grime at the moment? What is instrumental grime about?

[FO]: Instrumental grime is grime with that kind of noise and feeling that is so big at the moment. It doesn’t necessarily need an MC right now. When you hear this you’ll be as interested in it, with or without an MC. That for me is instrumental grime. The scene has been chucking out a lot of big instrumentals at the moment. It's a big sound that is reaching out to the masses again: it’s perfect for live performances with an MC, it’s perfect for your iPod, just sitting on the train, and it’s perfect for an upcoming artist to write lyrics for it as well. You can sit indoors and write lyrics to an amazing track. I get a lot of tweets saying, “Hey man, I’ve just been writing lyrics on your instrumental track.” I released 53 tracks of fire! It’s Footsie music that we played on our weekly show on Rinse FM and that hardcore fans kept asking me about.

[TB]: Do you see it as success when MCs start writing lyrics on your instrumental grime tracks?

[FO]: Yes, that is definitely an indication of success. It shows that I am cared about. It means the track meant a lot to the rapper or lyricist.

Link: Buy «King Original Series» here.

[TB]: War Dub is another term that turned up in the last year. What is war dub about?

[FO]: Well, War Dub was a battle between grime producers. We were producing dubs on the spot, in our houses, and everyone released their tracks online at a fixed time. It was about who is the best producer, but more in a joke way, not dead serious. This was war dub one. Many took part, all the big names, Wiley, Jammer, Rude Kid, myself, Teddy Music, Spiral, all jumped in and produced a beat. The winner could decide about the rules of war dub 2. War Dub 2 was about copying the style of another producer.

[TB]: It’s a great idea. Did War Dub 2 lead to parody as well?

[FO]: Yes, yes, you definitely make fun out of another producer. Then there was another war dub involving a Jamaican style soundsystem battle. It was all about producing heavy dubs, put them on your Soundcloud page. Who got the most plays became the winner. The scene got a lot of interest from it. All the big newspapers here wrote about it. I won some rounds because my dubs were heavy.

[TB]: Congratulations!

[FO]: Thanks, man.

Links: Check some remarks around the War Dub events via Do Androids Dance? and passionweiss.

[TB]: It is difficult to put sound in words, but let’s try it. In your war dubs and instrumental grime tracks what are bass lines, drum sounds, mid and high range sounds that you try to achieve?

[FO]: What range? I want in your face sounds. War Dubs need high impact. When you press play it should come in your face. I use a lot of harsh high frequencies, and heavy bass. Then, I enjoy laid-back tunes as well, to chill out. Here, I wouldn’t use the harsh frequencies of War Dubs.

[TB]: Your latest video «Piff» with the Newham Generals seems one of these chilled tracks?

[FO]: That’s for the weed smokers’, man. I’m rolling a spliff right now, as we speak.

[TB]: Chilling instead of bombing?

[FO]: Yes, you see what I’m saying. It’s the other side of the vibe.

[TB]: It is often argued that grime was being ignored outside grime community for a long time. Do you agree with that view? If yes, why is this so?

[FO]: Grime grew big quickly ten years ago. But then the scene didn’t produce enough good tunes to sustain the success. So some people looked away from grime and said «it could have been good, but it’s not as good as it could be». Now, I think grime is as good as it could be. There’s going to be a lot of great grime music coming out in the near future. I see grime in a good place. I think the climate has changed too. There is no real mainstream anymore. You’ve got things that ain’t that commercial getting commercial success. The consumer seems to want more underground sounds. The spotlight is more on the underground than ever before. In the Internet, no matter how harsh music is, it can still be big, you can’t stop that. You maybe cannot show it on TV, but you can’t stop millions from watching it online – you can’t stop something from getting ten million views. And ten million views is probably better than it being shown on TV - so that’s what’s happened. I think it is working in grimes favor, this change in attitude (see also «The Second Coming of Grime», in The Guardian, 27.3.2014).

[TB]: Dizzee Rascal is one of the grime artists that you work with that became a mainstream star. What are in your opinion the reasons that he went that far?

[FO]: He understood how to make a song, that’s all. He understands what it takes to make a song for a lot of people. Not everyone gets that, that’s not something for everyone.

[TB]: In his videos «Love this Town» or «I don’t need a reason» he seems to the take fear away from the often heard prejudice grime = crime.

[FO]: Yes, that’s what he was trying to say. You see a group of kids doing graffiti, and then coming around cleaning up. This goes against the general image grime has within London. He was trying to change the perception many kids have in the city.

Link: Watch the Behind the Scenes of «Love This Town»

[TB]: For the producers and MCs in your network, and for you, what does grime stand for?

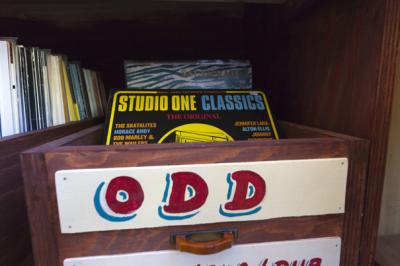

[FO]: I think we stand for originality and longevity. We also stand for all the stuff that built us - you’re who you are for many reasons, your family, many things. When I started as a kid, I began to feel that I was good at this. I got recognition, and that was very important. Now, I need to keep that recognition and stay on top of the game. My sound is a mass boiling pot of everything: from where I come from, from the reggae sounds systems, from Rastafarianism, everything is in there.

[TB]: And what do you think grime stands for within working-class communities in East London?

[FO]: Grime is a voice that can be heard around the world. I think that is important for the kids here. Kids are growing up knowing that if you can get big in grime you can get heard around the world. It’s a voice, it’s a vehicle, it’s a chance to get out of whatever situation you may be in. And it’s a chance to use the skills that you may have been given and blessed with. Grime within London right now is a big voice that you can use to be heard.

[TB]: So what are you plans for today after the spliff?

[FO]: Yes, I was going to get back to some studio work, and then just try some samples.

Biography

Published on April 17, 2014

Last updated on July 27, 2020

Topics

Can a bedroom producer change the world? How do artists operate in undersupplied conditions?

Place remains important. Either for traditional minorities such as the Chinese Lisu or hyper-connected techno producers.

How does Syrian death metal sound in the midst of the civil war? Where is the border between political aesthetization and inappropriate exploitation of death?

From Korean visual kei to Brazilian rasterinha, or the dangers of suddenly rising to fame at a young age.