Boris Blank – Painter of Sound

Boris Blank gained worldwide fame as a pioneer of electronic pop music and sound design. In this video-interview and podcast he talks about his passion for electronic music, the shift from analog to digital, and the magic of pre-sets.

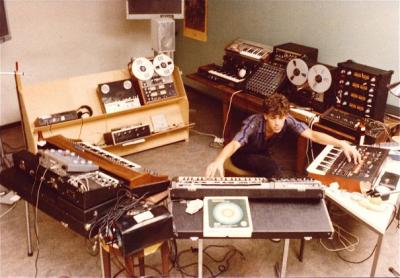

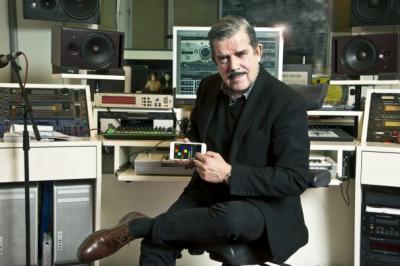

Boris Blank was born into a working-class family in Zurich in Switzerland on January 15 1952. While he was working as a TV repairman he taught himself skills as a musician and as a sound technician and started to experiment with the technological possibilities of cassette recorders, tape machines and magnetic tapes. Blank founded the pop band Yello in the late 1970s, first working with Carlos Péron and, from 1983 onwards, in a duo with Dieter Meier. This brought Blank worldwide fame as a composer and sound designer. The band has released numerous music albums and videos to the present day. For our research project Cult Sounds I interviewed Blank in his studio in Zurich and asked him about his passion for electronic music, his approaches in producing music, and the shift from analog to digital studio technology. Listen and watch glimpses of the interview, and read the full interview below.

Podcast (Excerpts from the Interview)

Video (Excerpts from the Interview)

Interview with Boris Blank

[Boris Blank]: Well, first I have to say that electronic music … equipment … electronics, are my world. It’s naturally very appealing to me to intervene in this world myself … using technology, just like a scientist who looks through a scanning tunnel microscope and finds that a seemingly (hesitates) smooth surface suddenly appears as a molecular structure. In a similar way you can use electronic tools or plug-ins to intervene directly in this molecular structure using all kinds of noises. For me, it’s a whole universe of sounds to explore.

It’s clear that the (digital world) – how should I put it? – the shift from the analog to the digital has been of great significance to me, in the sense that everything became much more comfortable. In previous years, I was still working with analog possibilities, with microphones, playing the bongos. I’d start the tape machine then stop it, and if I made a mistake I had to play the whole four-minute-long piece again on the bongos until my hands were bloody. The possibilities of accessing [what I wanted] were suddenly much easier with that move into new technologies, into sampling technology. I was able to record three or four accents, or samples of these bongos, and then play them back easily. It’s clear that was a big advantage to me.

My working method, however, hasn’t changed at all, whether I’m working with a mouse or with whatever potentiometers on my synthesizers. Whether I’m twiddling these knobs or working with a mouse, nothing has changed.

My path to getting a piece where I want it – this sound structure – is exactly the same. In this piece «Koladi-Ola» I had a sample: a vinyl record of noises from the BBC. There were zoo animals of all kinds, including a lion. I recorded the roaring of this lion and transposed it two or three octaves up, and the result sounded like a human voice.

This was then called «Koladi-Ola», and I used it in a piece, just like other alienated sounds such as sticky tape drawn over the edge of a microphone. The phasing sounded like a storm … or I threw snowballs against the walls of the house and made them into a bass drum. I set no limits to my imagination.

And I still think today that it’s very interesting for me to dive down into the depth of a sound as if looking at it through a magnifying glass, and to manipulate the sound in its core so that it turns into something very different.

I tend to work like a painter who has a basic idea of a picture and then he mixes the colours … after the first colour he adds more colours, step by step.

And thus ultimately I surprise myself with the kind of sound structure that emerges. And I … keep it, a bit like a squirrel burying its nuts. In that way I have lots of sound fragments, whole patterns – thousands of them, I’d say – that I work out over four measures and then hide away in folders somewhere or other. And when the time is right – because I’ve got a very good photographic memory for sounds – then I pick out these sounds and patch them together until I get what I want, what I want to hear. And my ear does the rest.

I think that’s like a painter with his paintings before he shows them in an exhibition. Or in my case before we release a new CD. I’ve got hundreds – at the moment it’s 70 – that have been left over that in the end don’t make it into the exhibition – in my case, that don’t fit the new CD of Yello. And there are still a lot that can be reanimated at some point, or that can still be finished, according to how they feel.

So I just work away, if you like. Not like a musician who has – how should I put it? – a democratic approach. They come into the rehearsal rooms, practice a piece and then present it like that. That’s perhaps the difference.

Yes, to be sure, there are coincidences and accidents and chance occurrences that play an elemental role in my music. I also live, like I say, from these chance occurrences. Sometimes things happen that astonish you and you think: wow, I’ve got to capture that, I’ve got to keep that. And sure, the chance experience is an important factor for me.

And of course I sometimes use pre-sets. It’s not a holy cow to me. That’s also a source of inspiration that really fascinates me to a certain degree. But as far as I’m aware, I’ve never used a pre-set just as it was.

I’ve always intervened in them, and them here and there, until they get a different face, and so that I can really use them as I feel is right.

I’d say that, of course, for emotional reasons, perhaps even for somewhat romantic reasons I still have my first synthesizers such as «Arp Odyssee» and a few others standing back there. It’s a kind of little archive that’s dear to my heart. But they’re not used much any more, so they also go a little out of tune. There are some, these «sequential circuits» that you had to keep tuning, these «Prophet 5s», whatever.

And back then I was already drawn to – what shall I call it? – modernity, the technology of the music world. I still am today, and that’s why I’m not so interested now in buying new analog parts just because I feel differently when I tinker with the potentiometers. As I said, I canmanipulating modulating do that just as well with a mouse.

If I’d like to bring in a bit of analog dirt – if – then there are tricks and ways of doing it.

And yes, I think that technology, progress in the music world, progress in the technological music world, always fascinated me in itself. I think of how, a long time ago, the harp was put on its side and turned into a spinet or a harpsichord, and people will have said: «Oh, it’s not the same, that’s already technological». And how ultimately the electric guitar was invented, with the pick-up, and when Bob Dylan stood up on stage with one, people said «That isn’t music any more!” and threw eggs and tomatoes at him.

I have always been in favour of progressiveness in music, that’s also why I’m still fascinated by the newest plug-ins that come onto the market today. I’m like a little kid.

I’m also really interested in the possibilities that still exist, where you could improve things. We have connections to Native Instruments in Berlin. And – like when I introduced the «Yellofier» – I’ve established really new contacts, also to «Ableton Live». I’m in contact with all kinds of people in Sweden who are producing sonic charge plug-ins. And I exchange ideas with various people, also in America. Whether they will respond and be able to achieve something – whether or not they will explicitly react to these ideas: that is something I doubt. But it’s certainly a matter of sharing ideas a little.

It’s funny. I was recently in Amsterdam and I was invited to a podium discussion, together with Paul Hartnoll of The Orbital, and I presented the «Yellofier» on a big screen on stage, and I was operating it and explaining it. And afterwards two little elderly men came up to me and introduced themselves.

The one was Roger Linn from Linndrum and the other was Dave Smith of Sequential Circuit, from back then. And they were fascinated and wanted to know how it works.

We then exchanged ideas. They showed me the new things that they’ve developed, and I explained the «Yellofier» on my iPhone a bit more.

Interview, camera, video & sound editing: Immanuel Brockhaus

Transcripts: Robert Michler

Englisch translations: Chris Walton

Biography

Published on May 28, 2016

Last updated on August 24, 2020

Topics

Digitization means empowerment: for niche musicians, queer artists and native aliens that connect online to create safe spaces.

Why does a Kenyan producer of the instrumental style EDM add vocals to his tracks? This topic is about HOW things are done, not WHAT.

Sampling is political: about the use of chicken clucks or bomb sounds in current music.

Snap