Since the beginning of the 21st century «new wave cumbia» has been growing as an independent club culture simultaneously in several parts of the world. Innovative producers have reinvented the dance music-style cumbia and thus produced countless new subgenres. The common ground: they mix traditional Latin American cumbia-rhythms with rough electronic sounds. An insider perspective on a rapid evolution. From the Norient book Out of the Absurdity of Life (see and order here).

Dreams are made of being at the right place at the right time and in early June 2007 I happened to arrive in Tijuana, Mexico. Tijuana had been proclaimed a new cultural Mecca by the US magazine Newsweek, largely due to the output of a group of artists called Nortec Collective and inadvertently spawned a new scene – a movement – called nor-tec (Mexican norteno folk music and techno). In 2001, the release of the compilation album Nortec Collective: The Tijuana Sessions Vol.1 (Palm Pictures) catapulted Tijuana from its reputation of being a sleazy, drug-crime infested Mexico/US border town to the frontline of hipness. Instantly it was hailed as a laboratory for artists exploring the clash of worlds: haves and have-nots, consumption and its leftovers, South meeting North, developed vs. underdeveloped nations, technology vs. folklore.

After having hosted some of the first parties in Australia featuring members of the Nortec Collective back in 2005 and 2006, the connection was made. In the following year I travelled to Tijuana with a crew of Australian artists and friends in order to participate in a series of cultural events featuring several dozens borderland artists part of the nor-tec scene. Local underground DJ Chucuchu made an indelible impression on all of us for mixing club tracks with cumbia straight from Mexican ghetto laboratories. These songs had all the energy of the classic Colombian Discos Fuentes recordings that make absolutely everyone dance, but sounded like they had been melted down and re-cast in the shape of a rocket that is blasted into outer space. It sounded so fresh, so vital and even more importantly to me, it felt dirtier and rawer than the Nortec Collective sound which I also loved. Returning from Tijuana, I spent some months scouting experimental cumbia from the psychedelic Amazon to urban Buenos Aires. I had to acquire those tunes mainly by downloading and ripping, as most of the sounds I was after had no official release. Then I started contacting many of the artists personally and asked them to send me their music directly.

I could never get enough of these tunes and got such a strong response from the dance floor that it was time to produce my own cumbia sounds. With the necessity of creating music that I couldn’t find enough of, I teamed up with my two musician friends Thomas «Soup» Campbell and Carlos Parraga to form the project Cumbia Cosmonauts and throughout our very first sessions we wrote the song Cumbianauts Incoming.

Cumbia Is a Bomb with a Century Long Fuse

«Cumbia is a bomb with a century long fuse» proclaimed the intro to an article by Jace Clayton (a.k.a. DJ /rupture) on the contemporary cumbia scene of Buenos Aires in the July/August 2008 issue of the hip New York magazine The Fader. Originating from Colombia, cumbia is a fusion of indigenous folk music combined with African and European musical culture. It had already been reinvented several times since leaving its birthplace, but this time it was different, something was causing cumbia to blow up all over the world – not just in Latin America.

«Digital Cumbia», «Nu-Cumbia» or «Nueva Cumbia» were some of the labels for this phenomenon – the next big thing? Much of the hype was coming from Argentina. As well as running whatsupbuenosaires.com (a directory of all the hippest cultural happenings in his adopted city), US-born Grant C. Dull was also directly involved by running the weekly Zizek club nights with fellow DJs Villa Diamante and Nim. Started up in 2007, in what Clayton described as a «safe club in the upscale Palermo Soho district – where both ‹real› blacks like myself and ‹los negros’› from the villa (slum) receive nasty looks in restaurants», the strong concept of Zizek being a laboratory for mixing, mashing up and remixing hip club music (hip-hop, house etc.) with the despised local variant of cumbia, became like a magnet for like-minded DJs and producers.

Two Californian DJs were also part of the early line-ups at Zizek: Oro11 (a.k.a. Gavin Burnett) and Shawn Reynaldo «who moved to Buenos Aires and found themselves swimming in a sea of experimental cumbia mayhem. After hooking up in the Buenos Aires DJ circuit, the boys quickly realized that many of the local cumbia sounds were never going to be properly released.» Back in California, the Bersa Discos label and the first vinyl-only release was launched in March 2008 featuring El Hijo de la Cumbia and Daleduro. These 12 tunes on black vinyl caught in its grooves the momentum of what had become a movement.

Almost simultaneously, the Zizek club night launched the ZZK record label to release the compilation ZZK Sound Vol.1 – Cumbia Digital. «In just a years’ time Zizek has been converted to Buenos Aires’ laboratory of dance, creating a scene of producers who reinterpret cumbia (as well as other Latin sounds) using technology and the resources of electronic music», read the sleeve notes. «This compilation is another step forward in consolidating this rich emerging scene and legitimizing this new hybrid and bastard genre we are calling ‹Digital Cumbia›.»

«When they ask me what type of music I play, I say bastard pop. It’s not hip-hop, not electronica, not cumbia. It’s more of a way of dealing with the music», Diego Bulacio (a.k.a. Villa Diamante) explained to Clayton. «When we started Zizek a year and a half ago, we debated whether or not to put ‹cumbia› on the flyer.» But Villa Diamante – whose DJ name means «Diamond Slum» – realized, that with a polish – or in his case a mash-up – the raw cumbia sounds from the «villas» (slums) of Buenos Aires would travel far.

Cumbia Is the Most Recent Mutation

Like all over Latin America, cumbia began establishing itself in Argentina as soon as recorded music and touring bands started being exported from the original source of Colombia, but it is the most recent mutation which made the biggest impact: cumbia villera (ghetto cumbia) which was born during Argentina‘s most recent economic meltdown (1999–2002).

Pablo Lescano is credited with almost single-handedly inventing cumbia villera, due to the enormous success as frontman of the band Damas Gratis. But according to international cumbia ambassador Toy Selectah, two other men were also extremely important in creating the potent new cumbia villera sound. One man is DJ Taz who helped producing instrumental tracks for Lescano called danzas and the other was Fidel Nadal contributing with important elements of reggae production.

Video not available anymore.

Essentially a danza is an attempt to turn classic Colombian rhythms into beats utilizing the production software Fruity Loops. Although sounding much simpler, the danzas lose none of the vitality and spirit of the original Colombian source material. DJ Taz went on to teach his danza and dub production aesthetics to the up-and-coming cumbia producers DJ Negro and El Hijo de la Cumbia, who Toy Selectah believes, are the true representatives of the new cumbia spirit. Only years later would I discover that some of those anonymous songs I had collected in Tijuana and made me want to become a cumbia producer, were actually these danza songs from Buenos Aires.

The Zizek crew invited ghetto hero Pablo Lescano to be part of their club nights, much to the chagrin of the genteel neighbourhood. Whilst cumbia had been present for a long time in Argentina, now as cumbia villera, it had become the official soundtrack for the poor urban masses. «Lescano injected real talk about drugs, girls and crime with the slang of the villa. At the same time, his unsettling keyboard style – all edgy play and multiple voice shifts per song – captured the queasy excitement of a ‹pibe’s› night out», writes an inspired Clayton, relishing the chance to hang out with the megastar Lescano during his time in Buenos Aires.

«Bands like Damas Gratis have turned to electronic toys and pushed aside intelligent music to stab us with lively rhythms and ghastly lyrics» writes Ariel Goldsinger in feigned elitist disgust. «This effervescent popular expression makes uncomfortable all those who anesthetize with second-hand hopes and media tricks.» Musically cumbia villera is indeed cheap, blocky and punctuated with «throw your hands in the air» to levels of exhaustion. Goldsinger goes on to say that it’s exactly this pushing aside of the status quo that «creates a space for comprehension.»

Like gangsta rap in the USA becoming a big part of listening habits far away from the ghettos that originally inspired it, this space of comprehension has been so successful in Argentina that these days «the most spoiled kids are playing cumbia villera. It’s already being taken out of the ghettos where it was born», said Dick El Demasiado on whatsupbuenosaires.com. «When I came here the first time [from Europe], people were complaining about cumbia villera. If a car stopped and cumbia was coming out of the windows, it was proof that society was going down. That’s the way they talked about it. I think the cumbia was most stigmatized here. This was the country where cumbia was most pushed down.»

The Slow But Incessant Degradation of Lunatic Cumbia

Some years before the Zizek hipsters put Buenos Aires firmly on the map for those searching for that Holy Grail called «the next big thing», there had been Festicumex; actually Festicumex 2. Hosted as a festival in Buenos Aires and Cordoba in 2003, Festicumex 2 united a vast array of artists and DJs interested in cumbia and featured on its line-up the likes of DJ Vampiros and a number of other artists who would go on to feature on the ZZK compilation Cumbia Digital such as Dead Menems, Marcelo Fabian and Fantasma.

Behind several of the bands on the line-up was Dick El Demasiado, instigator of Festicumex and given the title «godfather of the experimental cumbia scene in Argentina» by whatsupbuenosaires.com. As legend has it, the first Festicumex event was Dutch-born artist Dick Verdult (a.k.a. Dick El Demasiado) travelling to Honduras a year after Hurricane Mitch with a group of artists to simply film and observe the aftermath of the hurricane. The actual festival and cumbia came later. «I invented this festival – Festicumex… it never existed but we mentioned it as if it did», Verdult told whatsupbuenosaires.com. It was a situational stunt that worked. «Suddenly it started to live and I made all the music for all of these different artists. I made a song for Padre Theresa, for Hygienica Gonzalez as if they were all different persons and it just spread. Then at the same moment I figured that I may as well make something for Dick El Demasiado, who (at that time) I still wasn’t. I made a whole CD and I liked doing it and that’s how it happened. That was the first Festicumex. Then the second one we really did in Buenos Aires in 2003.»

So the true author of the surrealist history on cumbia called The Slow But Incessant Degradation of Lunatic Cumbia is Dick Verdult, using the pseudonym Ariel Goldsinger. Sprinkled with historic facts, poetic truths and surrealist wordplay, ‹lunatic cumbia› (and the movement it documents) movingly captures the spirit of cumbia, its makers and participants: desire, trance and escape. Also deserving to be mentioned as precursors for today’s nu-cumbia is German artist Uwe Schmidt and the label Multicolor Recordings, both being responsible for releasing electronic cumbia from Chile. During the late 1990s and early 2000s several electronic music projects experimented with cumbia: Gonzalo Martinez And His Thinking Congas, Senor Coconut, AtomTM feat. Tea Time and Mambotur. Several multicolor cumbias also featured on the cumbia compilation released by Italy-based publication COLORS (published by fashion label Benetton’s Communications Research Center), heralding it as «the modern electro-tropical sound… never meant to be contained by national boundaries.»

Cumbiadelic Experiencies of a Pilgrim

Cumbia digital could be considered a phenomenon, a movement, because it sprouted scenes simultaneously in several parts of the world. Whilst Zizek was running its club nights in Buenos Aires, in Mexico City a number of projects became part of the collective La Super Cumbia Futurista such as Afrodita, Sonido Changorama, Sonido Desconocido II and Grupo Chambelán. Unlike ZZK, these projects have not gained much exposure beyond their own borders, having kept their cumbia experimentation much more localised in a Mexico City context and also for celebrating the kitsch rather than the hip.

In a recent book published about the Mexico City sonidero movement the projects of this collective were derided as being «pseudo-sonideros», mainly for their parodying of the kitsch and as such are seen as making fun of the mostly working class «real» sonideros. Whilst this critique is perhaps valid for some of the projects, it also has to be noted that Diego Ibanez of Sonido Desconocido II hosted an insightful series of radio shows about cumbia called Su Majestad La Cumbia (Her Majesty the Cumbia) as a serious tribute to the (often) kitsch cumbia and its makers.

It’s also interesting to note that in the Mexican film Sin Nombre (Dir. Cary Joji Fukunaga, 2009) about teenagers escaping poverty and violence in Central American slums, Sonido Changorama (alongside Dick El Demasiado) featured in the soundtrack as representative of the «ghetto-sound». Sonido Changorama in a YouTube interview were not defensive about someone from their socio-economic background dedicating themselves to the traditionally lower-class genre of cumbia, but instead challenge people to look at the roots of the blues or rock’n’roll which today represent all classes.

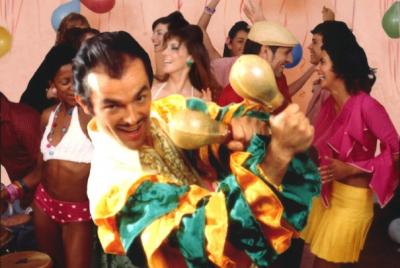

Meanwhile in the north-eastern Mexican city of Monterrey, Randy Salazar Jr. has been uploading documentaries of his «cumbiadelic» pilgrimages to find the lost temple of San Juanita Chinola. Referencing Mexico’s large rich culture of cults and living indigenous belief systems where shamans are still active, the Monterrey based artist claims to be on a constant quest to discover the true essence of cumbia, achieving salvation through his own «sacrodelic» music (and imbibing psychedelic food and beverages). Randy Salazar Jr. (a.k.a. Aaron H. Eivet) is also the VJ for tripped out and massively successful Mexican band Plastilina Mosh and in a situational way called into being his own existence as a cumbia producer and frontman of Grupo Chambelan, a pseudo-supergroup modelled on the likes of Mexican 70s/80s cumbia-pop icon Rigo Tovar. Through a multitude of video clips (labelled as «the most important Hollywood production in the history of cumbia»); videos documenting tensions within the band, mock interviews in the hyped style of commercial Mexican TV, Randy Salazar Jr. is the ultimate cumbiero by powerfully blurring the lines between dream and reality, kitsch and art, commercial pop and experimental music as well as irony and tribute.

Cumbia Is Ayahuasca

«In the late 60s a number of Peruvian musicians came up with a new sound – an Amazonian funk of sorts that came to be known as chicha. For reasons to do with geopolitics, class, language, power and dumb luck, their music never became the next big thing. This album is dedicated to the great bands of that era: Los Mirlos, Juaneco y su Combo, Los Hijos del Sol, Los Tigres de Tarapoto, Los Destellos and many more. May they be the next big thing in an alternate universe.»

Again a manifesto in the sleeve notes of a historic release, but this time it’s not a compilation, but an album called Sonido Amazonico! (Barbes Records, 2009) by a band from New York: Chicha Libre. As the cumbia digital movement was gathering momentum in 2007, Chicha Libre front man Olivier Conan had released the compilation The Roots of Chicha: Psychedelic Cumbias From Peru. «I freaked out», Conan told the Paris DJs blog about discovering chicha on a trip to Peru. «It was as if I recognized the music. It had all the elements of most of the music I had been interested all my life, but sounded completely original… The songs use every possible influence – from Andean music, to Amazonian rhythms, classical music, salsa, rock, Brazilian – you name it. This is the most satisfyingly un-pure music I know, yet it has the strongest identity. Although it borrows from every possible source, it sounds like nothing else.»

Like cumbia villera, as music largely by and for the working class, cumbia chicha was also despised by elite society and dismissed as commercial fodder for the masses and regrettably never gained much exposure outside Latin America until the release of Conan’s compilation. «I was particularly surprised by the response it got in Latin America and in particular in Peru, where it played a part in re-valorising the music», Conan told Paris DJs. Cumbia chicha being thrown as a boomerang to New York City and international record collecting hipsterdom made chicha not only palatable for Peruvian elites and re-ignite the careers of forgotten stars, but also inspired new young bands to spark up locally like Los Chapillacs and DJs Dengue Dengue Dengue! as well as Chakruna, who – thanks to the Internet – are attracting international attention.

The Cumbia Boomerang Keeps Turning and Turning

Continuing the tradition of the original Colombian cumbia recordings which were imported into Mexico by the shipload in the 1970s, Celso Pina is the most famous proponent of a style born in the shantytowns of Monterrey: Cumbia Colombiana. In 2001, Celso Pina teamed up with the producer Toy Selectah (also from Monterrey) to produce the massive cumbia hip-hop hit Cumbia Sobre El Rio feat. Control Machete & Blanquito Man, which has featured on numerous international compilations and film soundtracks (such as Babel and Amores Perros). The impact of this song was and continues to be massive and it was not surprising to see Toy Selectah reinvent himself as a cumbia and raverton DJ after the dissolution of his hugely popular hip-hop band Control Machete.

In the megalopolis of Mexico City, cumbia sonidera took on an altogether unique hallucinatory character, somewhere between stoned and tripping on acid. The fast accordion sounds loved in Monterrey and styled on Colombian cumbia vallenato did not really take off. Although even in Monterrey DJs would sometimes pitch down their imported fast-paced Colombian records to suit the Mexican taste for a slower style of dancing. But in Mexico City a whole scene of producers and bands focused on writing slower Cumbia rhythms with an exaggerated dragging effect caused by very late skanks and noisy scrapers. The faster songs sound like as if they’ve simply sped up these slower tunes. For the melodies organs and later synths were favored. Many songs are instrumental or have very simple lyrics more to hype the listener rather than a narrative. In the 1970s and 80s many cumbias from Ecuador, which for some reason share these characteristics, also featured heavily in the collections of the sonidero DJs. The boomerang of cumbia keeps coming back. Recent Mexico City productions, which are part of the original source materials that I collected in Tijuana and went on to inspire me for my Cumbia Cosmonauts project, sound like some of the danza ghetto sounds from Buenos Aires.

Cumbia Has Become a Jump-Off Point

«ZZK’s new vision of traditional Latin American music has had its way with cumbia but the sounds have evolved. Cumbia has become a jump-off point; an excuse to advance through musical ideas, where genres cross over and classification becomes a futile exercise. Without simplifying art by category, the moment has come to let it all flow. Music is music and this is how we enjoy it. A multinational album, ZZK Sound Vol.2 has got one foot planted in Argentina and the other dancing around the world.» The sleeve notes of the ZZK Sound Vol.2 compilation – released just a year after the debut of the label – dropped the subtitle «cumbia digital». Whilst dismissive of the genre, which propelled ZZK to global attention, it is also an accurate reflection of how cumbia digital had become an umbrella term for such a vast amount of musical experimentation that it was never going to contain everything it had inspired. The bastard genre providing the initial burst of energy for the ZZK founders had been mutating at extreme speed, to the extent that describing these newly evolving genres and subgenres all as «cumbia» suddenly seemed superfluous.

«The rise of cheap computers and music software piracy has led to an ever-increasing swarm of subgenres» writes Jace Clayton a.k.a. DJ /rupture in The National, who labels this phenomenon as «world music 2.0» (see article by Thomas Burkhalter). One of these new genres (which had actually existed in the Mexican rave scene for several years before attracting international attention) is called tribal guarachero (or 3ball). Its most famous proponents – teenage production crew 3ball MTY – have become superstars in their homeland. Toy Selectah was partly responsible for guiding 3ball MTY to commercial success. He explained in his lecture at the Red Bull Music Academy 2010, the most exciting thing about all these new music genres exploding in Latin America (and in fact all over the world) is not the music itself, but the fact it exists because of widespread access to affordable computers and music production software. «The idea of the periphery used here does not have much to do with a geographic concept, nor is it related with the gap between rich and poor, the developed and developing world, or North and South», writes Brazilian academic Ronaldo Lemos about the idea of world music 2.0.

«The musical scenes, as this small example shows, flare up in any place where there is a computer, creativity and people who want to dance.» (See also Norient-Post DJ Rupture on World Music 2.0) Back in Tijuana where it all started for me with cumbia, the Nortec Collective presents: Bostich + Fussible. These days they receive millions of YouTube hits on their videos and played at the opening ceremony of the 2011 Pan-American Games. There is a hungry new generation of Tijuana-based artists looking beyond experimenting with their own local folk music and the Pan-American genre of cumbia was a great starting point for the likes of Los Macuanos and Maria y Jose. But they have already moved on to inventing their own genre of ruidoson.

The attention now being paid to newer hip genres in various ways directly linked to the cumbia phenomenon – such as tribal guarachero (a.k.a. 3ball) and moombahton – has allowed cumbia to breathe again. It also has to be said cumbia has today become an established genre in hip circles all over the world and personally I now rarely find myself having to explain why my project is called Cumbia Cosmonauts as I had to only a few years ago. Starting the project, we had wondered whether naming a project with a genre of music we are operating in would eventually limit us and make us drop «Cumbia» to simply be called the «Cosmonauts». But at the time I dismissed the idea and whilst on our album Tropical Bass Station (Chusma Records, 2012) we also explore other related styles – such as dancehall, tribal guarachero, kuduro, moombahton and champeta – it is always cumbia we hold on to and cumbia is holding on to us.

Cumbia Is the Future Is the Past

Colombia may not be where much of the recent hype about cumbia digital or nu-cumbia originated, but always has to be respected as the birthplace of cumbia. However there is a rock project with electronic beats from Colombia riding the nu-cumbia wave that has made a big impact both in Colombia and internationally: Bomba Estereo. Their live shows are hypnotic, psychedelic and contain a strong element of African trance and it is of no surprise that the Bogota-born bandleader Simon Mejia spent some time in San Basilio de Palenque, South America’s first town built by escaped African slaves. Recently assisting in building this historic village’s first professional recording studio, Mejia and his colleague Santiago Posada also released a stunning compilation of recordings and a DVD film called People Of Palenque (Soul Jazz Records, 2012). It is also of no surprise Mejia mentions folk-tronica fusionists Nortec Collective as his biggest creative inspiration.

British producer Will Holland (a.k.a. Quantic) had already released a number of new songs in the style of the golden era of classic Columbian cumbia, cumbia-lovers have plenty more to look forward to following his permanent move to the city of Cali. Quantic recently released the deeply researched The Origins of Cumbia (Soundway Records, 2012) and collaborated with local project Frente Cumbiero to release Ondatropica (Soundway Records, 2012) which could be classed as both classic and nu-cumbia, if not digital.

Mario Galeano Toro explains that his project Frente Cumbiero is based primarily on sampling the classic recordings of Colombian tropical music from the 1960s and 1970s. They have released a number of important recordings, including an album collaboration with UK-based Guyana-born dub producer Mad Professor. «Those who still go to record stores will have noticed a tidal wave of classic (Colombian) cumbia compilations» writes Victor Lenore in a recent Spanish issue of mainstream rock magazine Rolling Stone about what he calls cumbia 2.0. «This is not an exercise in nostalgia», continues Lenore, «but a collateral effect of the power of so-called cumbia digital, a style that spread infectiously via blogs, mixtapes and pod casts.»

I believe classic cumbia and cumbia digital don’t just share the same roots, but at the end of the day for anything to be labelled cumbia it has to be cumbia. Cumbia is cumbia whether folkloristic, classic or futuristic. If it isn’t, then it isn’t. For you to make the distinction between what is and what isn’t is a matter of asking yourself: «Is this real?»