Through Space and Time

For Indigenous people, listening to music can function as an act of kinship, where identities are strengthened and acknowledged through building relationships with their environment. Read an essay by Indigenous musicologist and pianist, Renata Yazzie, inspired by the music of powwow singer Joe Rainey.

Yá’át’ééh shí éí Renata Yazzie yinishyé. Tóʼaheedlíinii nishłį́, Kinyaaʼáanii báshíshchíín. Bitʼahnii dashichei, Hónágháanii dashinálí. Akotʼéego, Diné asdzą́ą́ nishłį́. Greetings, my name is Renata Yazzie. I have introduced myself to you as a Diné (Navajo) woman by means of my four clans.

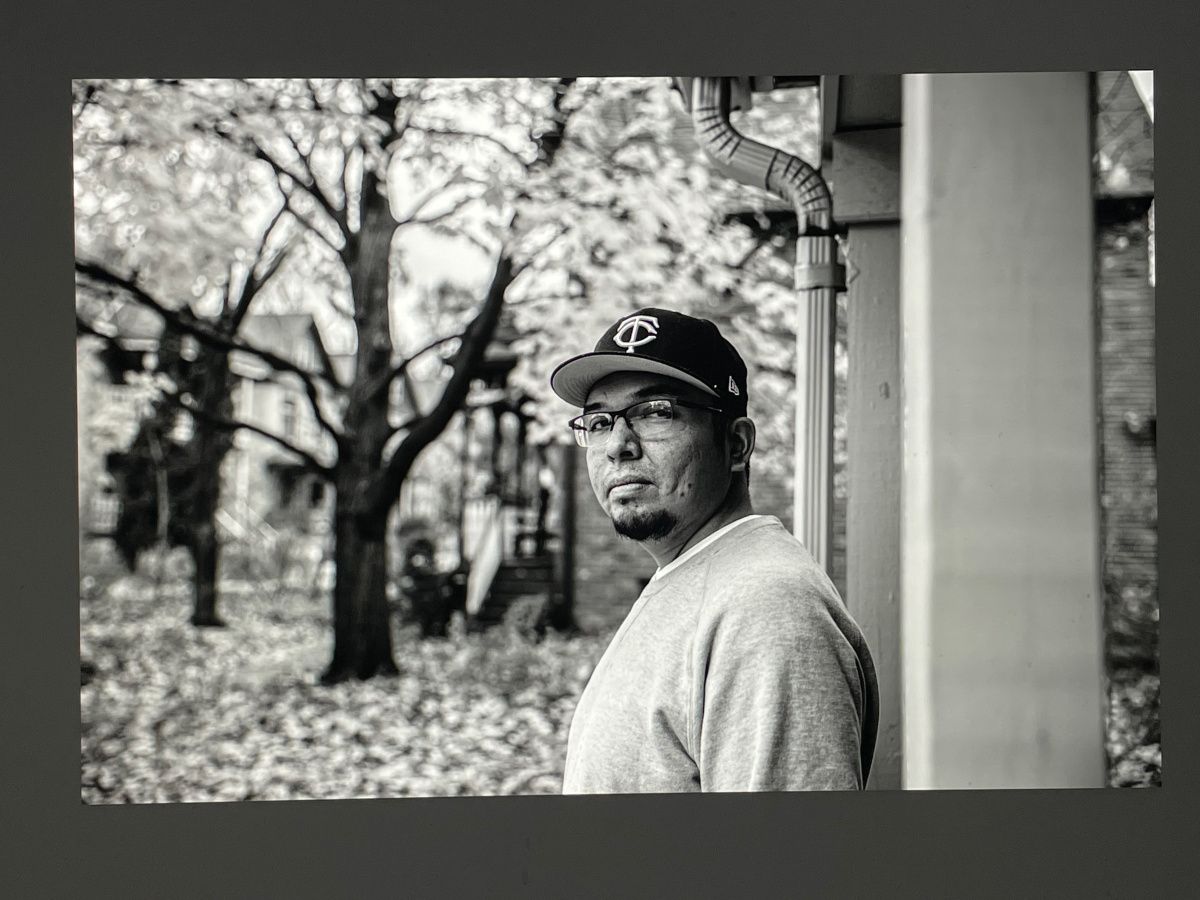

In September 2022, I came across an article from 1927 about the beginnings of music education in the United States. Catholic priests had brought music teachers to the Rio Grande Valley. The author dates the first music teacher, Cristóbal de Quiñones’s, arrival to San Felipe Pueblo sometime between 1598 and 1604 and the second teacher, Bernardo de Marta’s arrival to Zia Pueblo in 1605. These two men began teaching organ and voice before Johann Sebastian Bach was born. By 1630, music teachers at present-day Socorro, New Mexico, had also taught Navajos to play bells, trumpets, and clarions. In what we call the Southwest United States now, at least, Indigenous peoples have been engaging with Western instruments and musics for hundreds of years (Spell 1927). In listening with Joe Rainey’s album Niineta (37d03d 2022), a sound that provides comfort with the voices of old and new, I am reminded of my own people’s origins with music.

There is, however, a distinction to be made in most North American Indigenous languages between «song» and «music». In many cases, Indigenous languages do not have a word that directly translates to «music». And our ontologies of song differ from something you might find in a book of German Lieder. Song is an extension of language rather than an extension of music. Songs serve multipurpose functions that establish protocol, relate histories, and bestow healing, and aesthetics are secondary considerations. That isn’t to say we don’t create with beauty in mind. Rather, songs are meant to be both moral and aesthetic experiences. Both contain elements of beauty and both should be considered in an Indigenous listening experience.1

July 18, 2016. It was my second week in the German countryside of a small town in North Rhine-Westphalia. I had never been away from the familiarity of my Diné community for that long – temporally and spatially.2 In the mornings, I would log onto the iconic Navajo radio station KTNN 660 AM where the midnight hour (as it was at home), marked a continuous playlist of old country and western music and Navajo bands and artists of varying genres. In the most lonely moments, I could feel home through listening. A more abstract sense of beauty found in a sense of comfort where the popular sounds of my parents’ and grandparents’ generations gently caressed me, encouraged me, and reaffirmed my existence as a Navajo person in a foreign land.

An Indigenous listening experience is one felt and experienced by Indigenous people alone and as such, English words cannot do a commentary of it justice. But, as we ingest sounds, listening can function as an act of kinship where our identities as Indigenous peoples are strengthened and acknowledged through relationship-building with the entities around us.3 We listen through space and time to transport ourselves to a place that encapsulates the feelings and emotions our parents and their parents might have felt. And these listening traditions will continue with our children, despite how far away they might be from home, they can listen to our sounds, our songs, and our music, and feel a sense of home and belonging.

Indigenous music and songs written today, including Joe Rainey’s music and beyond, carry the same effect. As I listen to «ch. 1222», I am reminded of the day I walked from the field where our college campus powwow was in full swing, to my Diné/Laguna friend’s senior recital in Keller Hall. Both were distinctly Indigenous listening experiences in Indigenous sound spaces despite being vastly different in execution. One day our children will listen in kinship with us, to feel a sense of belonging, of home, and embracement of who they are at their core. This is one kind of Indigenous listening.

How do you listen?

What purpose does listening serve you?

- 1. Here I am considering the word «beauty» in an aesthetic sense of sounds that are pleasant to the ear and in a moral sense in that sounds may not be melodious but may still intend to move and inform the listener for an overall positive and enlightening experience.

- 2. The Navajo Nation is situated across the states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. At about 27,000 square kilometers, it is roughly the size of The Republic of Ireland. With approximately 400,000 enrolled citizens, we are the second-largest tribe in the United States. Not all citizens reside within the Nation. Most, including myself, reside in towns and cities close to the Nation while others choose to live further away and around the world. As Diné, we have called the Southwest our home for at least 10,000 years.

- 3. I am using the word «entities» to describe physical, abstract, and in some cases, spiritual phenomena around us.

List of References

This essay is part of the Norient Special «All in It Together» in collaboration with Rewire Festival 2023 as well as the Norient Special «Sonic Worlding».

Biography

Published on March 15, 2023

Last updated on April 02, 2024

Topics

A generative practice that promotes different knowledge. One that listens is never at a distance but always in the middle of the sound heard.

Place remains important. Either for traditional minorities such as the Chinese Lisu or hyper-connected techno producers.

Does a crematorium really have worst sounds in the world? Is there a sound free of any symbolic meaning?

From westernized hip hop in Bhutan to the instrumentalization of «lusofonia» by Portuguese cultural politics.

Specials

Snap