An average pop song counts around one thousand notes, while a typical Black MIDI track is several millions. Black MIDI composers – called «Blackers» – try to challenge computers, ears, and eyes with enormous numbers of super-short and dense notes. The home of this competitive, technology-based and transnational micro-genre is YouTube – and its community is growing fast. From the Norient book Seismographic Sounds (see and order here).

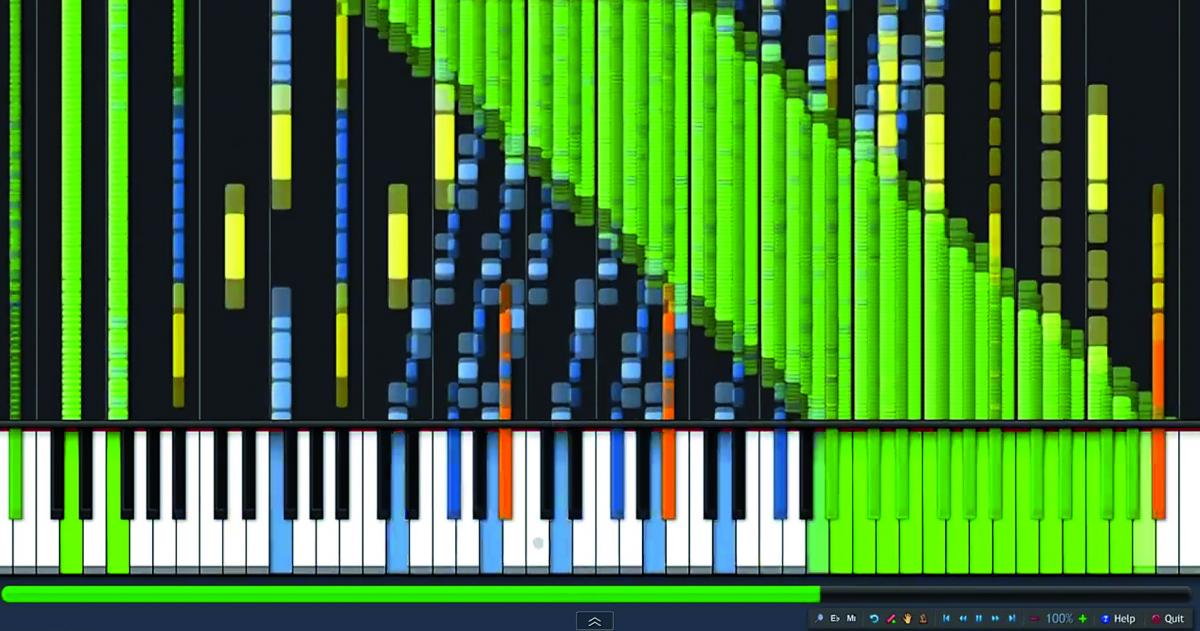

At the chorus, my computer started to stutter, leaving the catchy melody tumbling into chaos. It couldn’t handle the 1.1 million notes of EpreTroll’s Black MIDI version of Miley Cyrus’ «Wrecking Ball.» I tried to play a Black MIDI track in its purest form, from a MIDI file that triggers notes on any software synth (or hardware synth capable of MIDI). A million MIDI triggers pulled, my computer crashed. So, I turned back to YouTube, where Black MIDI tracks can be consumed in the form of screen recordings, safely for my computer. It looks better, too: the screen recordings on YouTube show the one million notes playing in programs like Synthesia, a piano training program in the style of the Guitar Hero game. It becomes an audiovisual thing: notes are presented as colorful bars falling down the screen, hitting a keyboard on the bottom.

What Counts is the Note Count

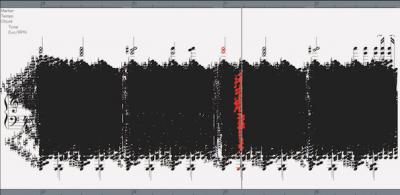

Black MIDI started in Japan around 2009 when users on the video platform Nico Nico Douga started publishing remixes. They used only one virtual grand piano, but a very high number of notes - once hundreds of thousands, and now dozens of millions. These numbers are proudly noted in the titles or descriptions of Black MIDI tracks. They rise higher and higher by the year - an important part of the competitiveness of this scene. The basic method is to fill up the score with lots of very short notes, keeping the main melody in the front. Some of the note triggers are clustered on lower pitches to create beats, some create long notes to sound somewhat like string synths, some are stacked to form very fast arpeggios imitating the fake polyphony of early monophonic game soundtracks - for example, the typical Commodore C64 sound. Some are just there for visual purposes, creating patterns, images or words when played in Synthesia or similar programs.

In standard notation, the scores become just a black cluster, hence the name Black MIDI (see images). Needless to say, these scores are impossible to play by hand on a real grand piano. Black MIDI seems to echo 20th century experiments with the mechanical player piano by composers like Conlon Nancarrow (player piano with punch roles) or Marc-André Hamelin (MIDI piano) who wanted to challenge notions of playability by both humans and machines.

A Transglobal Japanophile Community

Other predecessors might be found in Tracker software of the 1980s and 1990s and its use in the Demo Scene (which also contains the aspect of challenging hardware and showing programming skills). This history is all googleable knowledge, possibly known to many of the mostly teenaged Blackers; however, these don't seem to be main references for them. Black MIDI is deeply rooted in game culture: the medium, the competitiveness (the note numbers are its high scores), the bragging about the computer’s capability of playing the files without lagging, the pseudonyms, the similarities to fast-paced music games, the arpeggios, and the compositions. The most popular of the blackened songs are from computer and video game soundtracks, most notably the Japanese cult series Touhou.

Touhou are «bullet hell» games with millions of colorful bullets raining down the screen that the player has to avoid. So, these 1.1 million notes were actually bullets, and I was in note hell. This is a Kawaii version of war though where everything’s kind of pink and the tunes are as saccharine and catchy as J-pop hits. And pop it is. Black MIDI is juvenile fun that adults don’t get, beautifully senseless, in a feverish adolescent high speed; it’s related to game culture and the digital folklore of vernacular remixes and parodies; it’s distributed via the global mainstream channels of user-generated content, where people from different continents who never meet in person and don’t know each other’s real names form spaces of belonging: true pop of our times.