Unfinished Frequencies

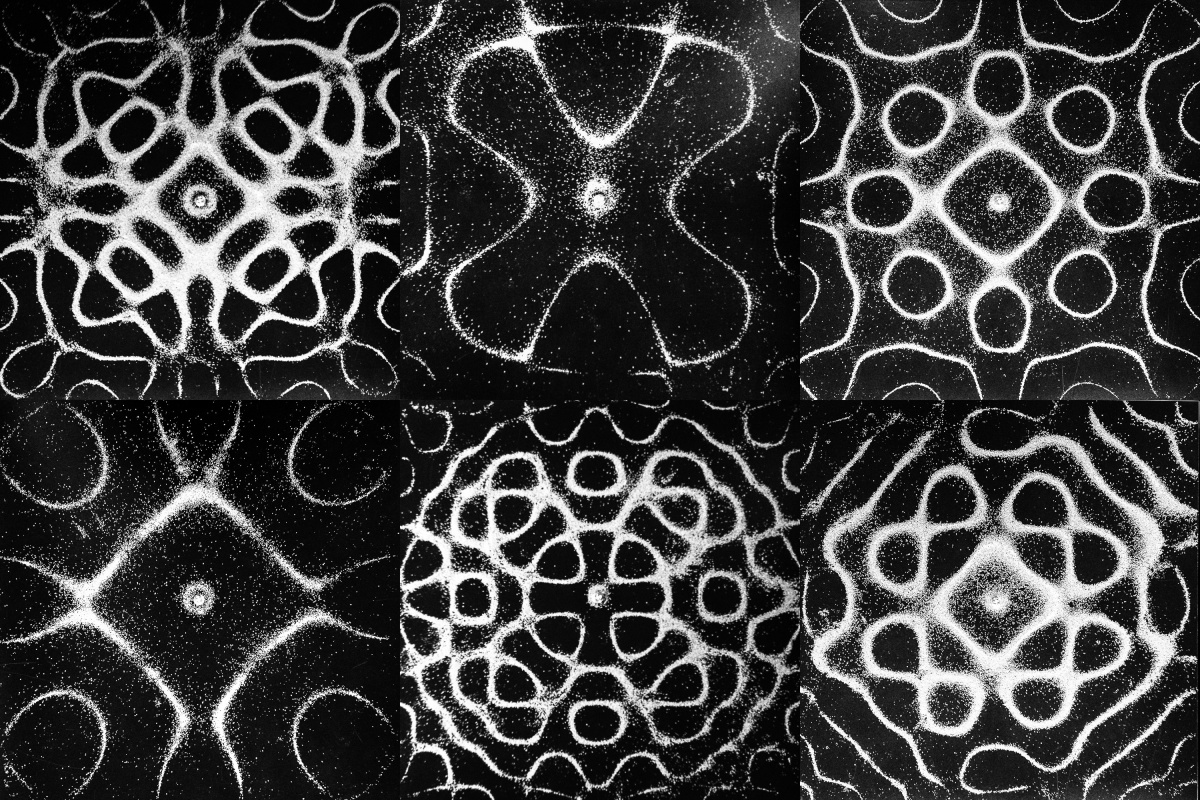

Visiting an old friend becomes a journey through sound, memory, and change. Inspired by the pounding bass of Kenyan artists Lord Spikeheart and Slikback, both performing at Rewire festival 2025, this short fiction piece reflects on old routines and what inevitably shifts.

My out-of-place vehicle chugged through that neighborhood of houses with sharp angles, precise curves, muted hues. Where was Bahati? In our last chat, he’d shared a link to Slikback’s «Dread» which was now playing in my car, assaulting the silence of the old houses which have aged uniformly so that the exterior walls all appear identically patchy and pale.

The bassline vibrated through the wheel beneath my hands, a restless energy at odds with the stillness outside. The old houses, their tiled roofs faded to the same dull off-red, seemed unaffected. There are variations in the layouts of the gardens but every house has rosemary sprouting, and an odd plant which they call all rasta, because of its dreadlock appearance.

The track’s erratic energy reminded me of Bahati’s way of jumping into things, never hesitating, always ahead. I envied that. At inception, tree seedlings were counted, distributed, and planted across the vast landscape dotted with windowless, doorless, and roofless concrete structures. Bahati abandoned everything in his old flat, and moved here with only the clothes on his back. New career, new life. His housewarming party, three months after that move, impressed me. He moved to a different tempo – spontaneous, buoyant, and driven – I envied it.

Later, Bahati joined the maintenance committee of his neighborhood association. When he speaks about their meetings I visualize all of them not seated around a table, not facing computer screens for online meetings, but gathered in a soundproofed and padded room. Over «EMBLEM BLEM» by Lord Spikeheart, their words collide, a spirited negotiation among the too bossy, too soft, or too particular types.

This isn’t an oddity in Bahati’s corner of our city where discussions are erratic and fragmented yet agreeable to him. The committee has resisted all tenants’ requests to install diesel-powered electricity generators despite the unreliability of the electricity supply. Diesel generators are too noisy, it asserts. This location of numerous trees is ever cloudy. The sun is up there, but its power is out of reach. Regardless, the committee awaits suppliers’ proposals for installing solar power in their homes.

Out of my car, I half ran to his door. I rang his doorbell. Bahati had told me about his quest to solve the hard-water problems of the neighborhood. He had grown tired of the hard water’s calcification ruining his water faucets and forcing repetitive replacement of shower heads and water kettles. The stained toilet bowls irritated, and so did crockery and cutlery that never looked clean or shiny no matter how thoroughly it was washed.

Every week, blue tankers marked SOFT WATER circled the neighborhood like ice cream vendors shouting about their precious commodity. «Soft water!» A tanker thundered past my little car. That refrain repeated, as I turned the doorknob. Finding the door unlocked, I went in. «Bahati?» I called. The television was on with its volume muted. Nobody was in the kitchen, but there were dishes on the rack and other signs that someone had been there. I heard movement and a machine’s low hum from the backyard, and used the door in the kitchen to access it.

Now the hum was accompanied by a scrubbing sound. Bahati’s tool shed was open, and an array of unfamiliar equipment was spread out on the grass lawn. Bahati had boasted about his recently installed tiny spinach garden. More signs of life; the garden had obviously just been watered, wet green leaves glimmering in the sunlight.

The sound I’d heard got louder, and faster, and then glitchy. I got closer to the shed, ignoring my racing heartbeat. It felt reminiscent of «Data» by Slikback, of the clunking and reverberation, younger versions of us dreaming and busying ourselves in the old abandoned yard. Failing all attempts to restore our collection of junky cars never deterred us.

Inside, two men somewhat disguised with safety glasses on their faces, overalls, and grimy hands, were squatted and absorbed by the machinery they were working on; banging, tightening pipes with a wrench, and sudden whooshes of water flowing out of the hose pipe and sputtering into a metal bucket.

The men nodded at me, while Bahati popped up behind me, and offered an explanation, more like a confession. «My phone was dead … I’m charging it right now.» He said. «Let me show you.» From his pocket, he unfurled a piece of paper with detailed sketches. «See, we are desalinating our water!»

More water splashed, but his hand on my shoulder guided me around his machinery’s unsteady thrumming that had kept him too absorbed.

This piece is part of the Norient Special Where Sound Becomes Witness, a publication in collaboration with Rewire Festival 2025. It assembles essays and audio pieces that explore how sound can cut through the noise to bear witness, inspire solidarity, and reimagine our shared reality. Curated and edited by Philipp Rhensius and Katía Truijen.

Biography

Published on March 03, 2025

Last updated on March 10, 2025

Topic

Does a crematorium really have worst sounds in the world? Is there a sound free of any symbolic meaning?

Special

Snap