A Viral Horn for the Global Village

The expression «om telolet om» refers to a practice for which teenagers in suburban areas of Indonesia ask bus drivers to play their telolet (special polyphonic horns), which they then record with cellphones and share as YouTube video compilations. In 2016, «om telolet om» went viral, reaching the EDM music community and generating several remixes featuring samples from various videos. In this article, our author analyzes the phenomenon problematizing it in relation to global and local cultures and creative production in contemporary music.

The telolet (onomatopoeic rendition of its sound) is a polyphonic horn composed of different speakers or «funnels» (corong) connected to a console comprising six to twelve buttons. Each button controls a single speaker/note or a pre-programmed combination of notes: a melody. The apparatus is powered by a battery and it’s known for its impressive loudness.1 While it is possible to hear these horns in other countries as well,2 they have become a symbol of Indonesian digital culture.

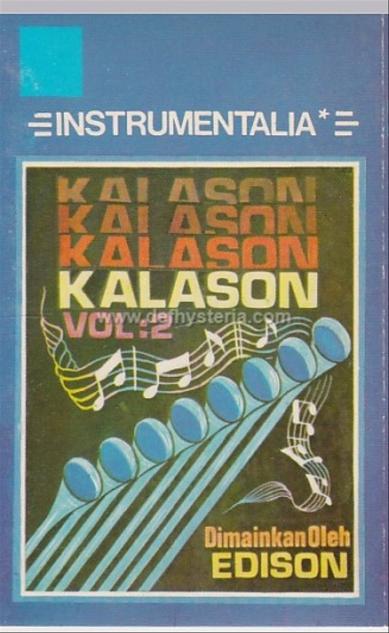

A Sumatran «Ancestor»

Surprisingly, the history of the horn as an instrument is much older. Bus drivers in Indonesia have always been cultivating interest in car horns since the introduction of the Chevrolet «Division 74» buses in West Sumatra during the 1970s. Various companies would feature playable keyboard horns:3 organs with pipes fitted in the engines of long-distance buses – independent but indeed similar to telolet – known as kalason oto Gumarang; Gumarang being the first of the many bus companies which integrated the horn. Drivers would play folk and pop songs both to entertain passengers and attract potential clients. The fascination for this new instrument eventually led to a proper genre marketed in cassette format,4 where an ordinary Casio keyboard was used to imitate the sound (Barendregt 2002).

After the bus system changed throughout Indonesia in 1975, the kalason slowly disappeared along with the buses of the period.5 Nowadays, few people are still able to play it and the instrument has become a «rare catch». Despite this, the passion for the role of driver and for vehicles as symbols of freedom and mobility remained strong, generating aficionados’ clubs, festivals, and contests.6

Sir, Play the Horn, Sir

In December 2016, the internet started celebrating the viral catchphrase «om telolet om» (Google Trends 2019), which made web surfers amused and confused. The phenomenon originated in Java approximately one month before its spread when kids and teenagers in the suburban neighborhoods of Pantura (Rijal 2016, Winarno 2016) decided to hang out near the major highways, trying to make bus drivers play their telolets by showing them signs on which the famous catchphrase was written. Thereafter, the kids started collecting these, as they label them, «cool, funny, and unique» sounds in the form of videos made with their smartphones, sharing them as YouTube video compilations.

The horns finally reached famous EDM artists such as Marshmello and Ummet Ozcan7 when Indonesians started using the catchphrase on Twitter and Facebook as a hashtag to express appreciation to the DJs they love.8 Henceforth, people started witnessing telolet homage remixes featuring the famous horn samples. Indonesia bursted with happiness, seeing its culture going global (Soriente 2017). No one claimed royalties or acknowledgement for those sampled sounds. Instead, participants and scholars interpreted «om telolet om» as a digital, national heritage depicting Indonesia’s identity as a whole, and thus belonging to everyone (Soriente 2017, Rijal 2016).

Recognition or Orientalism?

Now that the internet seems to have lost interest in «om telolet om», we may be brought to dismiss it as a bunch of funny, albeit peculiar, horn sounds. However, if we look at it from a political perspective, the phenomenon expresses different power relations at play and issues in the field of representation.

The telolet samples are the double-edged sword at the center of the problem: on the one hand, Indonesians obtained higher degrees of social capital thanks to digital infrastructures and the «glocal» circulation of sound.9 The practice allowed kids to be noticed by their beloved musicians, who acted as a vector of Indonesian culture in the West. On the other hand, these remixes use the samples in a way that perpetuates the idea of a bizarre country, reducing telolets to mere exotic sound bites.

In this peculiar case, using samples is far from being a harmless practice. In fact, the use of samples can either be a way to recognize how people culturally select, catalogue, and archive sounds, or yet another occasion in which sounds are bound to the Orientalist narrative. In exchange for some tempting, momentary fame on the surface of media communication disguised as advocacy, the protagonists of practices are forced to abdicate the possibility of self-representation, while sounds themselves, stripped of their context and significance, are banalized and depoliticized.

- 1. Which has even «forced the police to enforce legal noise threshold» (Aritonang 2016).

- 2. Some examples are Malaysia (M.A. S.T 2019), Bangladesh (Rehmat Hingolja 2019) and India (Noushad shad'z 2019).

- 3. Companies such as PNB, ANS, Palapa, NPM, Gumarang, and more.

- 4. Maybe, to explain the passion Indonesian people show for horns and loud noises, we can also mention how in general noisy ambiences and loud sounds have always haunted the islands since the 20th century, filling Indonesian urban landscapes with deafening calls to prayer, ear-splitting parties, and roaring engines. Soundscapes like these are often described as «rame» (or «ramai»), meaning, according to R. Anderson Sutton, «busy, noisy, congested, and tangled» (Sutton 1996), and as having a proper aesthetic feeling of «busy noisiness» for which «what can be an aural cacophony to Western ears can resound as pure, bustling excitement for an Indonesian», and thus proving the strong predisposition in enjoying and appreciating such sounds and soundscapes (Keen 2018).

- 5. Even though, to be accurate, we know that buses of the Gumarang company again used the sound of the kalason (Barendregt 2002).

- 6. «Om telolet om» even developed a sort of sound branding: many bus companies, even if not all of them, are very interested in having their distinctive telolet (Ndan Zaidan Chanel 2018), which is usually employed in parade-like convoys of buses belonging to the same company driving on streets and highways.

- 7. A complete list should include also DJ Snake, DJ Zedd, Dillon Francis, Martin Garrix, Alesso, the Chainsmokers, DJ Soda, Hardwell, Ben Nicky, and Fedde Le Grand.

- 8. This eventually involved not only musicians but, in a second moment, other famous personalities such as Hillary Clinton (Toar 2016).

- 9. Using the term «glocal» I follow Khondker’s concept of «macro-localization», which «involves expanding the boundaries locality [Sic] as well as making some local ideas, practices, institutions global», expanding from Robertson’s original definition (Robertson 1983, 100) of «glocal» as «the interpenetration of the universalization of particularization and the particularization of universalism».

List of References

This article is part of Norient’s online publication Sampling Politics Today, published in 2020 as part of the research project «Glocal Sounds – Re-Working and Re-Coding Place References» (No. 162797), funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and supported by the Bern University of the Arts HKB.

Bibliographic Record: Monteanni, Luigi. 2020. «A Viral Horn for the Global Village». In Sampling Politics Today, edited by Hannes Liechti, Thomas Burkhalter, and Philipp Rhensius (Norient Sound Series 1). Bern: Norient. DOI: 10.56513/nftg6449-11.

Biography

Published on September 24, 2020

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topics

Sampling is political: about the use of chicken clucks or bomb sounds in current music.

Why do people in Karachi yell rather than talk and how does the sound of Dakar or Luanda affect music production?

From Korean visual kei to Brazilian rasterinha, or the dangers of suddenly rising to fame at a young age.

What happens when U.S.-blogger collects african music and offers it for free? What is the difference between «textually signaled» and «textually unsignaled»?

About the ups and downs of cross-cultural creativity: Korean reggae, vaporwave, and the worldwide Hindu Holi festival.

How did the internet change the power dynamic in global music? How does Egyptian hip hop attempt to articulate truth to power?

From Self-Orientalism in Arab music to the sheer exploitation of Brazilian funk music by acclaimed artists: how exotica examine aesthetics playing with the other and cultural misunderstandings.

Special

Snap