NairobiConscious: Through the Airwaves

Can political music achieve its intended impact when it has to be packaged and presented as entertainment? Can music that interrogates society’s values and asks the serious questions make itself heard above the popular music promoted through the mainstream channels? Kamwangi Njue grapples with this question as he traces the history of conscious music in Kenya through his own experience as a teenager growing into an artist and critical observer.

«I believe, in fact, that attempts to bring political protest together with ‹popular music› – that is, with entertainment music – are for the following reason doomed from the start. The entire sphere of popular music, even there [sic] where it dresses itself up in modernist guise, is to such a degree inseparable from past temperament, from consumption, from the cross-eyed transfixion with amusement, that attempts to outfit it with a new function remain entirely superficial.»

Theodor Adorno (n.d.)

My early memories of music are fragmented across different listening phases which have continued to pull each other around as I try to make sense of my listening habits.

Before I got attuned to the FM stations, there was music I heard from elsewhere – Newton Karish, all that Katitu Boys Band, and also music from stories I would hear from my cousins, that ranged from «village boombox fictions» and families notorious for throwing parties that were profiled by what was played and the packs of Eveready1 batteries spent per night.

There was also Catholic church music, there was folk music, kiraka drums, and wathi songs.

I came of age with the radio just before the early days of kapuka releases. The knob became my friend as I chased unknowns that might speak to me through the airwaves of the city’s radio. As I explored radio shows and formats, I realized that some music like reggae and hardcore hip hop were given less airtime.

Growing up in a Mbeere2 village meant that Nairobi was this imaginary place, but through the music I heard, I would try to explore my sense of the city through these rhythms.

I fell in love with Kenyan hip hop in particular the day I heard DJ John Rabar play «Fanya Tena» on Nation FM’s Homeboyz DJs takeover hosted by Talia Oyando.

The track’s hook conveys both defiance and aesthetic Swahili/Sheng3 hardcore rap. As the posse cut of Juliani, Johnny-Boy (RIP), Kitu Sewer, and Agano – all of whom were in the Ukoo Flani Mau Mau rap collective – raps through the instrumental, several scenes emerge. Their style of writing and immersive talent are evident in the way they weave rhymes together.

«Fanya Tena» follows the intro in Ukoo Flani Mau Mau’s album Kilio Cha Haki.

That was my conscious indoctrination. And I continued to chase after that fix ever since.

Conscious Music

Conscious music implies music that implores and comments on social issues, from calling out policies to narration displayed in poetic skills. But as Joyce Nyairo reminds us, conscious doesn’t have to necessarily imply protest music, for even pop «love songs reflect our deepest humanity, we must always interrogate them…».

In Kenya, there has been music whose consciousness is felt by the body nation through ways a song signals change and cultural shifts.

In 1947 after the Second World War, the African soldiers of the King’s African Rifles,4 who had enlisted in the military Entertainment Unit, returned back to a popping Nairobi straight from Burma where they were fighting for their colonial masters. Some formed a band which they called Rhino Band.

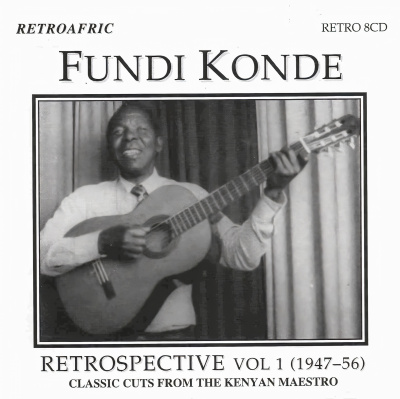

Among those who returned is one Fundi Konde. The string pluck maestro had trained in music at a Scottish Missionary School. He enlisted in the King’s African Rifles in 1944, as a 20 year old, in the Entertainment Unit.

Fundi Konde is largely credited as the first black musician in Nairobi to step into a studio to record.

In May 1963, an Anthem Commission was formed by the colonial government. It included Graham Hyslop, George Senoga-Zake (Rhino Band), Peter Kibukosya, Thomas Kalume, and Washington Omondi. This Anthem Commission was tasked in coming up with a Kenyan National anthem as independence neared.

Graham Hyslop encountered Galana Morowa Menza, an ex-serviceman who auditioned a Pokomo lullaby for the commission, a tune that he remembered from his childhood. For Hyslop and crew, this is the moment they were looking for. They arranged the anthem from the Pokomo lullaby.

The final version of the anthem was recorded in Kiswahili and English on September 25 and 26, 1963. It was sung for the first time on Independence Day immediately after the British anthem.

Music after Independence

Music after independence was composed of patriotism, hope, and optimism, which only lasted until the murder of Josiah Mwangi Kariuki in March 2, 1975. After the assassination, Joseph Kamaru released «JM Kariuki». The song not only describes the grisly murder, but also asks the government to provide the answers to the death of an innocent man. The song was banned on June 20th 1975.

After independence, more musicians were coming from other parts of Kenya to Nairobi. This saw an influx of tribal musics and African-owned record labels. Benga entered Nairobi from Luo Nyanza, Lake Victoria shores, which then found mugithi music from the Kikuyu5 and the mwomboko dance. This fusion managed to influence each other, together with Kamba and Luhya music.

Joseph Kamaru sang in his native Kikuyu language. His mugithi-benga fusion cut through Nairobi with the sharpness of his proverbial messages, which were political and cultural in equal measure. How else can popular music be?

Kamaru became a voice of critique and transformation. His music could be danced to and could be educational. It was coded in proverbs and modernity that oozed on guitar riffs and nostalgia for when morals guided a culture. This radical social commentary provided a base for what Nairobi conscious music of the future would strive to be.

After the death of Kenya’s first president, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, in 1978, the then vice president, Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, was sworn in as Kenya’s second president. For his politically charged lyrics, Kamaru found himself in trouble with the new president.

From the mid-1970s on, the political unrest in Zaire made it impossible for the lingala musicians to make a living. Many more musicians joined the 1960s Zaire bands that recorded and performed in Nairobi, but this new exodus was lasting, courtesy of better recording studios.

April 1980, Zimbabwe gained independence and Bob Marley passed through Nairobi for the second time, on his way to Harare for the country’s independence day celebration.

In 1982, there was a coup attempt.

Revolutionary: Rastafarianism and Emceeing

When reggae music’s Pan-Africanism, outcry at violence instigated on Black people across the diaspora, and embodiment of strong spiritual significance, made its symbolic and mythical return to the Nairobi audience, it found an audience that was just experiencing postcolonial power at play. The hope and promises of a futuristic prosperous body nation was caught in a whirlwind of corruption and political dirty games. So reggae, and not music for specific communities, communicated with urban and younger city dwellers who, with advancement of technology and the desires it brings, echoed their identities and ideas, anchoring authenticity toward social change.

Papa Lefty (RIP 1996) was the founder of King Lion Sound, one of the earliest sound systems in Nairobi.

By the early 1990s, Jimmy Gathu got a gig with the new TV station KTN, where he played videos of music from international musicians. Among his 30-minute slots for each day that included reggae/dancehall, there was also a hip hop slot.

Hip hop in New York was entering its second golden age. On the West Coast, gangsta rap was king. These videos getting played on the TV introduced many people in Nairobi to this new music genre.

Archiving and AirPlay

This keeps on throughout the 1990s where the advancement in music distribution and marketability almost foreshadows formats such as live band music, specifically elements of benga. Maybe for nostalgia’s sake and preservation purposes, it’s the reason why compilations such as Fundi Konde – Retrospective Vol 1 (1947–1956) 1994, were released.

Archiving initiatives such as Shades of Benga by Ketebul came to fill in the gaps between the new music genres from the West and what the younger generation call old music, such as benga. By extension, the Afro-fusion genre stems from here, where musicians such as Eric Wainaina and Suzanne Owiyo anchor themselves. These different genres are still in conversation with each other, as they share similar political backgrounds.

For Kamau Ngigi, one of the founders of Kalamashaka , this new music resonated with them and those from the ghetto more than anything else. The poetic language and boombap sound, as well as the sampling of music from the older generation, soon had them writing and rapping.

In the following years, however, radio became a battlefield of content. Music that was deemed to cause social anxiety or believed to rub the government the wrong way, was slowly shunned and removed from the airplay because it was bad for business.

Conscious music as a voice of critique and transformation was swept to the undertones of wanna-be revolutionaries, in favor of music that wouldn’t make you interrogate much about serious life issues.

- 1. U.S. brand of electric batteries.

- 2. The Mbeere or Ambeere people are a Bantu ethnic group inhabiting the former Mbeere District in the now-defunct Eastern Province of Kenya (Wikipedia).

- 3. Sheng is a Swahili and English-based dialect, originating among the urban youth of Nairobi.

- 4. The King’s African Rifles (KAR) were the British colonial military within East Africa before and during the First World War.

- 5. The Kikuyu are a Bantu ethnic group native to Central Kenya (Wikipedia).

List of References

This essay is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Nairobi» curated and edited by Raphael Kariuki and Kamwangi Njue.

Biography

Shop

Published on May 07, 2022

Last updated on August 31, 2022

Topics

Why New Yorks’ underground doesn’t give a fuck about Trump or why satirical rap in Pakistan can be life threatening.

From Beyoncés colonial stagings in mainstream pop to the ethical problems of Western people «documenting» non-Western cultures.

About Tunisian rappers risking their life to criticize politics and musicians affirming 21st century misery in order to push it into its dissolution.

Special

Snap