To what extent do sampling practices maintain or disrupt an exoticized ideal of indigenous populations? In this article, the Brazilian research collective Laura confronts two sampling strategies performed by different artists in Brazil. On one hand, a worldwide EDM artist who repeats the clichés of exotizing cultural appropriation through an usual strategy of sound sampling. On the other hand, indigenous artists who use rap as a mode of enunciation, in a process that the authors understand not as sound sampling, but as cultural sampling.

What happens when we approach sampling strategies from a critique of the historical process of colonialism? The relationship of the colonial encounter between West and non-West is highly asymmetric in terms of knowledge and power. Such asymmetry is a typical effect of the cultural imaginary of colonialism, which has produced and reproduced for centuries a romanticized, essentializing, and exoticizing caricature of the cultural other.

Reinforcing the Loop of Colonial Violence

This reproduction is exactly what is at stake in the sampling practice used by the DJ and producer Alok Petrillo aka Alok. During his brief stay in the Northern-Brazil Mutum village in 2015, Alok sampled sounds made by the Yawanawá indigenous people located in the Brazilian Amazon. In the track «Yawanawá», the indigenous is capitalized as a decorative element of EDM, resulting in the production of a sonic caricature in which the native is featured as a childish being in a pre-linguistic state, whose vocal expression is reduced to a babble emptied of any political existence. It is a clear example of what ethnomusicologist Steven Feld (1996) described as the cliché effect of a «pygmy pop». This commodification of exoticism that transforms native elements into decorative cultural components is an endogenous procedure in the historical line of Western capitalism. Therefore, Alok’s sampling procedure comes to our ears as a late echo of the transatlantic trade and the ghosts of colonialism that still haunt South America.

The track «Yawanawá» was produced along with a documentary, which reproduces every cliché of the colonial fantasy. The West projects on the non-Western its fascination with an a-historical essence, and acts out a social altruism of pure collaboration and celebration of diversity. These clichés are ultimately decorated with the value of transcultural inspiration, which rhetorically legitimize the commodification of the cultural heritage of others in the form of artistic inspiration. This discursive corpus forms a loop of primitivist fantasy and postcolonial exploitation, in which the agent of the global industry reaches out to a local population with an apologizing spirit, but ends up neutralizing the indigenous as a political subject in the current Brazilian public sphere. In a nutshell: what is taken as a desirable commodity that leads to an «incredible journey» (Alok 2016, 18:57) only reinforces the loop of colonial violence.

Rapping for Broader Visibility

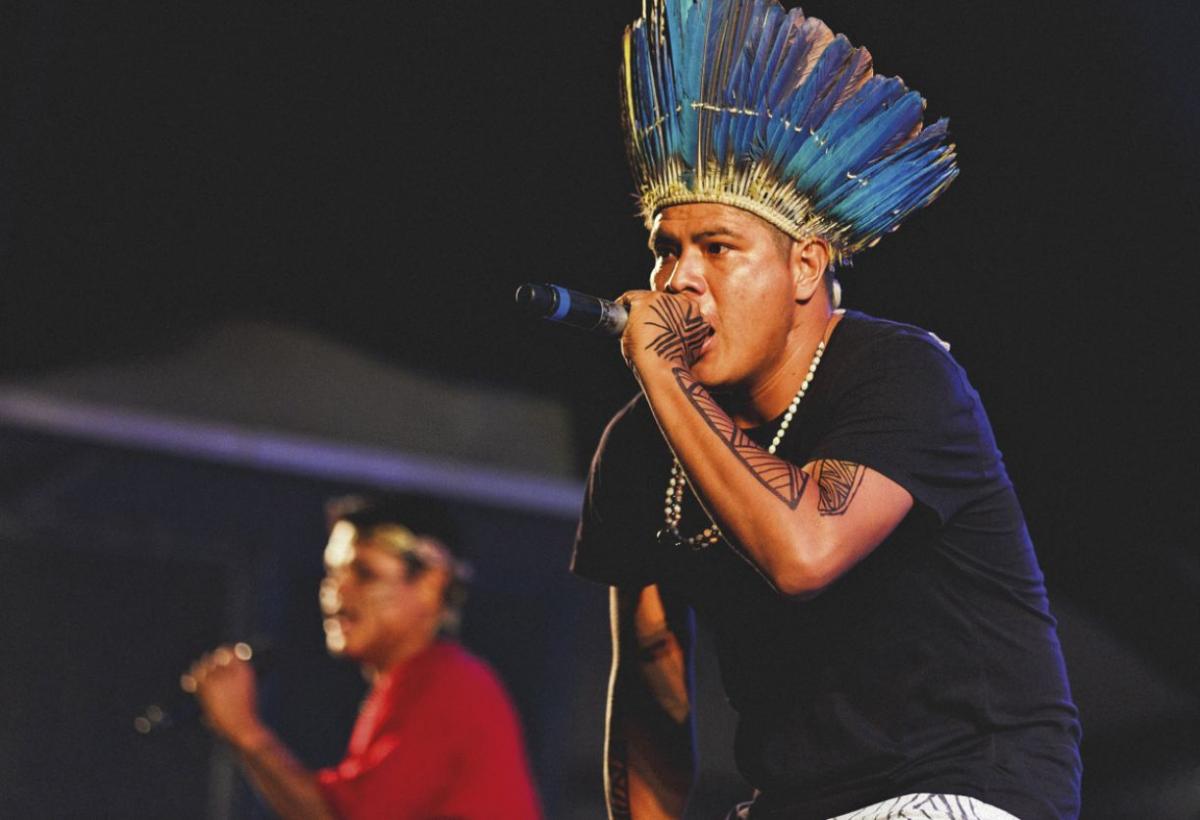

If on the one hand, this sampling made through a colonialist framework produces a sonic caricature of a voiceless primitive, on the other, the construction of a sampling practice led by the indigenous rap group Brô MC’s allows for a non-hegemonic indigenous visibility. The group is based in the Indigenous reservation of Jaguapiru and Bororó in Dourados, Central-West-Brazil. It was formed in 2008 by brothers Bruno and Clemerson Veron and brothers Charlie and Kelvin Peixoto, and was joined by Dani Muniz in 2012. Their lyrics, sung in both Portuguese and Guarani, seek to affirm the Guarani and Kaiowá identities which are strongly ignored by the mass media. As Bruno Veron (2007, 23:18) points out, Brô MC’s want to dismantle the recurring idea that «the indigenous only serves to invade other people’s lands».

Bruno says that their first contact with rap was through the radio broadcast of local groups such as Fase Terminal, which resonated with the social issues faced by indigenous youth. From this contact, the artist began to create his own lyrics to address the concerns that haunted the indigenous reserve community. The first beats were provided by a local schoolteacher and today they are made by the producer Higor Lobo. The Brazilian scholar Luciana de Oliveira (2016) argues that the quest for an insertion in the Western regime of visibility became a political strategy for indigenous people since the late 1970s, in order to regain their territory and resist agribusiness advances. Although the Brô MC’s artistic practice was initially received with suspicion by some of the elder members of the village, it is gaining community support for its ability to express the reality they lived. Their music is driven by a desire for visibility as it is expressed by the song «Eju Orendive» («Come with Us»): «nde ndokatui remanha remanharon che rehe mbaeve nde rehechai» («you can’t look at me/ and if you look at me, you can’t see me»).

Brô MC’s perform a process of «indigenization of rap» (de Oliveira 2016, 213) in which they appropriate the rapper’s performativity, sampling a mode of enunciation of an urban pop culture to affirm their existence and their own voice: «ava mombeuha ava koagagua» («indigenous voice is the voice of now», from the track «Koangagua»). Thus, they can express their culture to both the karaí kuera (white world) and to themselves. The friction between urban pop culture and the Guarani-Kaiowá indigenous context comes up through the perception of a capitalist neocolonial political project that makes invisible, exploits, and kills indigenous people for its own benefit. Here, sampling means to incorporate an urban vocal practice to expose the contradictions of the Guarani-Kaiowá current way of life, which puts in evidence the historical struggle to keep their lands.

Indigenization of Rap

Brô MC’s voice is an antithesis of the anti-political sentiment repeatedly demonstrated by Alok. The same primitivist fantasy of colonial exploitation that still haunts indigenous people is also responsible for a reductionist understanding of these cultures. This idea reduces the indigenous to a homogeneous cultural category, in which they are supposed to remain static and atemporal. In their lyrics, performance, and use of language they resist the «forms of subjectivation attributed externally by prejudiced or stigmatizing views. So what is at stake is not a capture of the experience of being indigenous by rap, a mestizaje, but a process of indigenization of rap» (de Oliveira 2016, 213). Through cultural sampling, Brô MC’s occupy the Western visibility regime as a way to express and make their own narratives heard.