Katey Red, Sissy Nobby, Big Freedia: these successful Sissy Rappers turn New Orleans around. Gay rappers carry the torch for bounce, but not all local rappers are comfortable with that.

Club Caesar’s LLC is advertised on the radio as «under the G.N.O. bridge», and it literally is. To get there from the East Bank, it’s necessary to overshoot it by almost a mile by taking the Gen. De Gaulle exit, and then loop back around through the Fischer housing project. Behind Caesar’s is the Mississippi River, and across Monroe Street from the club is a stately mortuary. At 10 pm on a recent Tuesday night, the vehicles parked on the block were an idiosyncratic collage: a pair of NOPD units, the Q93-FM mobile broadcast van and a fleet of immaculate white hearses.

Inside, the bar is low-ceilinged and spare, with wood paneling, linoleum floors and a few scattered bridge tables, similar to an old VFW Hall or Elks Club. Flo Rida’s springtime hit «Low» pumps from the speakers as people start to trickle in. It’s a weeknight, but the fans are dressed to impress – girls in shiny stilettos and guys in crisp, fresh oversized polos with a scattering of bling – ready to pop and wobble to Big Freedia and Sissy Nobby, the bounce rappers who hold down the mic at Caesar’s every Tuesday and Friday night. It’s popular among New Orleans DJs to remix R&B radio hits with the manic, skittering rhythm that characterizes bounce, and the later it gets, the harder and faster the beat pounds underneath warbling ballads and lazy hip-hop cuts from Usher and Lil Wayne.

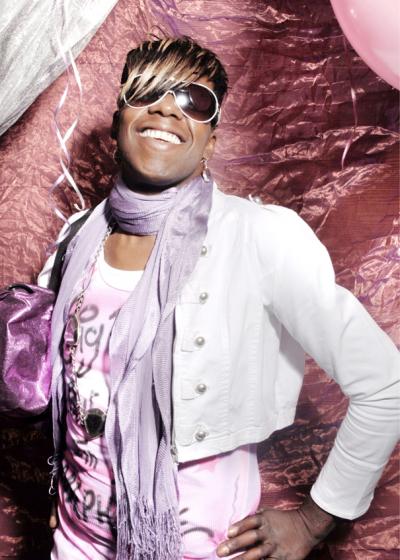

Just before 1 am, Big Freedia comes in – a tall, rangy-bodied former high-school cheerleader with a cute Rihanna-style cropped hairdo, dressed down in jeans and a T-shirt and swinging a casual, trendy, red handbag on her wrist. She has a self-possessed, almost regal vibe in counterpoint to Nobby, who’s short, curvy and cute, a ball of baby fat and energy. Together, they’re two of the most popular and prolific (and busy – the pair performs at least four nights each week) acts in local bounce today. They’re also both biologically male, gay, and as out-and-proud as they can be. In the lexicon of bounce, they’re punks, or more often, sissies.

As hip-hop evolved throughout the 1980s, the music coming out of New Orleans largely sounded like what was happening in the rest of the country: a singsongy, Sugarhill Gang-style vocal rhythm over fat, methodical beats and soul and funk samples. That all changed drastically around 1991 and 1992, when «Where Dey At» – which is generally accepted as the first bounce song – was recorded in two versions, by MC T. Tucker with DJ Irv and shortly after by DJ Jimi. The new sound was stripped-down and raw, intended to drive a dance floor with its speedy, infectious «triggerman» beat and repetitive lyrics that were more call-and-response than narrative. A sample of the 1986 song «Drag Rap» from a New York duo called the Showboys became a hallmark, as did lyrics that called out (and demanded responses about) your ward, your school or your project, which gave the sound its uniquely participatory groove. Like the triggerman beat and the «Drag Rap» sample, catchphrases and lyrics also migrated from song to song in a sort of mutual homage. (Dozens of bounce songs use the DJ Jimi-coined chant, «Do it baby, stick it», or DJ Jubilee’s «Trick, stop talkin’ that s**t/ And buy [your name here] his outfit.») More often than not, the lyrics were also really, really dirty, describing sex acts and preferences in lewd and gleeful anatomical detail.

Bounce ruled New Orleans’ club and block-party scene for years, though the only national bounce hit of the 1990s was Juvenile’s «Back That Azz Up», which hit No. 19 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the last year of the decade. Locally, bounce spawned dozens of artists and club hits, including the duo Partners-n-Crime, whose songs «Heron Baby» and «Thank You Miss Lilly» (a paean to their local weed dealer) stood up alongside more vanilla club bangers like its classic «Pump the Party». The saucy Cheeky Blakk got the bounce lyrics «Suck dat p***y for a pork chop» onto a Rebirth Brass Band album (2001’s Hot Venom). Juvenile wrote bounce lyrics for DJ Jimi before breaking out as a solo artist. And the Tupac Shakur of New Orleans, the late Soulja Slim, recorded bounce tracks as Magnolia Slim before veering into more gangsta territory.

After almost 10 years of block-party sovereignty, a new chapter in bounce opened in 1999, when the local Take Fo’ label – home to artists like Choppa and DJ Jubilee – issued Melpomene Block Party, the first full-length release from Katey Red, a gay, transvestite MC from Uptown's Guste Apartments, otherwise known as the Melpomene projects. Katey is 6-foot-2, slender and graceful – and at 29, about to celebrate a decade as New Orleans' original sissy rapper.

«Oct. 21, 1998, that was the first time I got on the mic», she remembers. It was at a block party in the Melpomene, and her friends egged her on mercilessly until she got onstage. Katey would walk around the courtyards of the Melpomene and the halls of her school, rapping, and early versions of her songs were already well known. «And when I got up there, everyone knew what to say back», she remembers. Her fan base was instant and enthusiastic. Katey and Freedia befriended each other early on, and Freedia got her start singing and dancing as a member of Katey’s backup group, Dem Hoes. Soon, with Katey’s encouragement, she became a solo artist in her own right.

Through the door opened by Katey sashayed a flood of sissy rappers in the early 2000s, including Freedia and later Nobby, plus artists like Vockah Redu, Chev off the Ave., Sissy Jay, Sissy Gold and the group SWA: Sissies With Attitude. Some, like Katey and Vockah Redu, performed in wigs and dresses; others were less visually outré, but still identified as «sissies». As the originator and most prominent sissy rapper, Katey earned a wealth of publicity, including a 2000 New York Times article. (With this raised profile came intra-scene spats – some, Katey says, arranged as publicity stunts and some genuine — that resulted in hilarious tracks like Vockah Redu’s «F*** Katey Red», which teases the rapper for having big feet and shopping at Rainbow.)

She followed Melpomene Block Party, with its neighborhood-based call-and-response anthem «Loco New Orleans», with 2000’s Y2Katey: The Millennium Sissy, also on Take Fo’. Also in 2000, Vockah Redu put out Can’t Be Stopped, and 2002 saw the release of Chev’s Straight Off the Ave. and the two-CD compilation by DJ Black-N-Mild, Battle of the Sissies Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. The next year, Freedia dropped her debut, Queen Diva, with the exuberant local hit single «Gin In My System». The sissy rappers also recorded several collaborations with artists who did not self-identify as gay, including 10th Ward Buck, Gotty Boi Chris and the well-respected female rapper Ms. Tee. Their take on bounce used the same frenetic beat style that defined the 1990s, but favored lighter, cheerier samples than the ominous, ubiquitous «Drag Rap». One of Katey's favorite samples is the unmistakable opening of the Jackson 5's «ABC». In the bounce tradition, sissy lyrics are also graphically sexual – Freedia often calls herself, cheerfully, «Big Freedia, the d*** eater» – and their shows, like straight shows, often feature a lineup of girls bending over and shaking their butts in the air onstage. (The rapper Mr. Meana commented, in a sentiment echoed by several straight male rappers, «We got to hear that music in the club, because that's what makes the females do all types of dances.»)

In Ya Heard Me, the first bounce documentary film, the rapper Devious D. complained that sissy shows would invariably be compromised by gay male dancers performing alongside the rappers. There would be four hot girls, he said, «and one big booty man just ruining it». (In an interview, Matt Miller, an Emory University doctoral candidate who is writing his dissertation on Southern rap, said, «I'm thinking, ‹Come on. Your sexual preference is being catered to by a ratio of four to one.›») Bounce shows in general – as the rappers report, and as personal experience has shown – attract cute young girls dressed to the nines by the hundred, and sissy bounce audiences look to be 60 to 70 percent women. Where the girls go to dance with their butts in the air, of course, the boys will follow. So even naysayers like Devious D wind up hearing a lot of unapologetic songs about gay sex, not to mention songs that skew slightly political, like Freedia and Katey’s defiant duet «Stupid», whose hook calls out men who have sex with men on the «down-low»: «You are too stupid for calling us guys / You know you tried it so stop telling them lies.»

In New Orleans, open homosexuality and cross-dressing have strong precedents in mainstream popular music, perhaps especially in the black community. Patsy Vidalia, the openly gay, transvestite host at the Dew Drop Inn, was the toast of the town for more than two decades, ruling the stage of the legendary club from the late 1940s until the late 1960s. Her drag costume balls were a de rigueur party stop on Halloween nights for years. She performed and socialized with a star-studded roster of local artists, including Allen Toussaint and Raymond Lewis, and she taught Irma Thomas «Hip Shakin’ Mama» – Vidalia’s signature song – which Thomas still occasionally performs today, although without the racy lyrics that were Vidalia's trademark.

The gay soul singer and occasional cross-dresser Bobby Marchan also occupies a solid spot in the local R&B pantheon. Marchan, in fact, probably has claim to being the original sissy, or at least a proto-version: his record label and production company, Manicure, was responsible for promoting and recording some of the earliest bounce artists in the 1990s, and had a hand in the startup of the Cash Money label. His own 1987 version of Clarence Carter's «Strokin’» may be the first recorded version of the popular bounce lyrical pattern of calling out the names of different New Orleans housing projects for audience members to answer by claiming their own. A lyric on «Stupid» («Am I a boy or a girl? Nah, I'm Katey Red») even recalls one of Marchan's favorite lines – «I’m not a woman, I'm not a man – I’m Bobby Marchan!»

Matt Miller and Stephen Thomas directed Ya Heard Me, which premiered at the Contemporary Arts Center last spring. Miller forwarded Gambit Weekly a paper he’d written on the sissies for a graduate seminar that made mention of a common academic concept in performance studies – that the act of performance is, in some ways, feminizing by default to the performer, who is making himself or herself the object of the audience's gaze. Acting on that idea literally, though, in the hyper-masculine – often blatantly homophobic – climate of hip-hop music can be a little more problematic.

The local hip-hop radio personality Wild Wayne hosts a networking event, Industry Influence, on the first Monday of each month at the Hangar in Mid-City. In June and July, two panel discussions were dedicated to the legacy of bounce. The June conversation, though, dissolved into a tense argument when an audience member asked the members of the panel – Partners-N-Crime (PNC), legendary producer Mannie Fresh, 5th Ward Weebie, DJ Jubilee, DJ Black-N-Mild and others – to comment on the state of the music, and the first response, from one of the members of PNC, was: «It’s gay.» A great deal of shouting ensued. Wild Wayne blogged about it later, at www.industryinfluence.blogspot.com, comparing the panel to a family reunion: «You know the reunion that starts with big hugs and warm feelings, but ends with arguments and hurt feelings cuz somebody says or does something stupid. There’s the perfect example. The panel that was supposed to educate & enlighten and pay tribute to the ONLY contemporary New Orleans originated genre of music and its colorful characters spiraled out of control. ...»

«The music has a lot more to it than just the stigma of being gay or transvestite», explained PNC’s Mr. Meana a few weeks later, theorizing that after the first 90s wave of popularity there was a lull that allowed the sissies' style to take over, because of their multiple releases and frequent shows. «When we took a break, it was left open for them, and now it’s oversaturated with their style of bounce.» Now, he worries that the flamboyance of the sissies will overshadow bounce’s overall legacy. When Plies played at the Venue in early July, Meana remembered, the national rap artist asked to hear the hottest local track.

«And the DJ played one of those songs», he said. «What the f*** is that? Come on, play some Soulja Slim or something, play Dizzy’s ‹Work Ya Elbows›. The DJs act like they don’t have any other music to play. It's nothing against them. It’s just the only thing I hear now in bounce is gay, and it’s something I don't want my children to hear», Meana added, although he was careful to note that gangsta rap and his own songs glorifying drug use are also off-limits in his house. «They can listen to the radio version», he said. «But I hear the same complaint (that bounce is gay) at the barbershop, at the studio, everywhere I go.»

At the end of the day, the sissies enjoy an uneasy acceptance, both for carrying bounce’s torch and, of course, for keeping the dance floor jumping with women. But in the working-class African-American South, male homosexuality can be a difficult identity to maintain. After Katrina, Katey Red evacuated to Dallas and was active as a performer for the year she spent there, but after returning to New Orleans, she took some time out of the spotlight. In an interview for Ya Heard Me that was filmed shortly after Katrina, Katey acknowledged that she was emotionally exhausted and was dealing with it partly by living and dressing as a man. Katey went back in the studio, dropping the single «Been Gone For a Minute» on Take Fo’ in early 2008. When we met, she wore casual daytime makeup, bright plastic jewelry and a floppy pink hat with teal jeans and a fresh white tee – not flamboyant, but hardly passing. Her plans involve going into the studio soon, she says, but a lack of transportation – she recently sold her car – combined with promoters not meeting her price have precluded live shows.

Not every sissy bounce artist finds it as easy to maintain a strong public identity. Both Freedia and Katey say that their families are positive presences in their lives. («My mama's heard me say d*** eater’ so much she doesn’t even care», Freedia told me, as she made plans to head to her mother’s house for dinner.) That support helps, as does the tight substitute-family structure the sissies create with their friends. When we met at a coffee shop, Katey brought a younger friend, Chantrell, who she referred to as her «gay daughter». She also jokingly rebuked Freedia for not keeping a tighter leash on Nobby, who didn’t show up. («She’s your daughter», Katey said.) But for all their local popularity, being gay and out in the rap world can attract negative attention. Both Freedia and Gotty Boi Chris recalled situations at shows that felt unsafe.

«In some places, you know, it’s not fully understandable», Chris says. «They’re not okay with a man talking about another man. I’ve seen it turn out ugly. You know how people are when they don’t understand something.» While Freedia and Katey were attending Cohen High School in New Orleans, they performed with the marching band, Freedia as a cheerleader and Katey, who now teaches baton-twirling to high school students, as a twirler. Their classmate, now the sissy rapper Vockah Redu, was also on the baton squad, but she marched in drag, and audiences were rough on her.

«She would march with her hair done, and makeup, and people would be yelling and even throwing stuff», Freedia remembers. Matt Miller recalls filming interviews with sissy rappers during the making of Ya Heard Me and dealing with some of that static.

«We’d be interviewing Freedia, and there’d be some guy in the background just heckling», he says. In Miller’s research, he observed more than one artist who first emerged on the scene as a sissy having second thoughts. Both Vockah Redu and Chev, during the time the film was being made, stopped self-identifying as gay. Chev, according to Miller, plans to release an album addressing the transition called A Change of Plans.

«I asked Vockah, how is it being a gay rapper?» Miller says. «And he said, ‹I’m straight; the gay thing is just part of the act.› And it’s definitely a complicated issue. You have to figure, there are people who are bisexual, so who am I to say that somebody can’t decide not to be gay?»

DJ Jubilee, who still holds down a weekly gig playing bounce at the Cricket Club Sunday nights, has endured, earning the title «King of Bounce» for the genre’s entire tenure. His signature track, «Get Ready», provides the building blocks for dozens of bounce songs with its litany of called-out dances: walk the dog, monkey on a stick, the Eddie Bauer and the Chuck D, not to mention the «sissy boom». His longevity makes him philosophical about the music’s ups and downs, which is probably a wise tack to take. In 2003, federal courts ruled against Jubilee in a suit he filed against Juvenile, denying the claim that the hit «Back That Azz Up» was a blatant rip-off of his own «Back That Ass Up», a song he’d been performing for years. Juvenile made millions; Jubilee is still a teacher by day in the New Orleans public schools.

In 1999, Jubilee says, he brought Katey to the Take Fo’ label, sensing she was something exciting and new, and her decade of popularity proved him right. «I’m still doing my thing in the street, on the mic, in the club every week», Jubilee says. «And they’re hustling and grinding like me, so they hot. People new to the music might say that bounce is a gay thing, but they don’t understand. And there’s no big contract coming through right now, so what are you fussing for? We all scraping and scrapping. If you get mad at that, you’re not doing your homework.»

Today, Katey, Nobby and Freedia are going full-speed ahead with nothing but bounce. Three, four or five late-night shows a week full of cute girls enthusiastically popping make theirs a scene to be reckoned with. Out of a bounce movement that once comprised dozens if not hundreds of artists, the sissies now make up a plurality. 5th Ward Weebie recently dropped two bounce singles, «Bend It Ova» and «Ride Dat Beat», and 10th Ward Buck performs regularly at the Bottom Line club. But Gotty Boi Chris, a bounce rapper in his early 20s who got his start as one of Freedia’s backup singers, stands as the newest face in mainstream bounce. He is one of several artists who feel that bounce's tide is turning, and the sissies represent only a sub-genre. Chris had a regional hit last year with «Blocka Blocka», a bounce song at its core, but one that notably explores more complicated production than most of the bounce canon.

«Everybody eventually comes to an upgrade», he says. «You have to transform from an old generation to a new generation. Freedia and Nobby are like an upgrade from Katey Red, and there’s really not a lot of bounce artists still doing it. And eventually I’ll probably get to a new level with my music, too.»

Bounce is coming up on its second decade and its presence is still powerful in New Orleans. It still propels a dance party like nothing else, and of course, New Orleanians cling tightly to our indigenous culture. Some of the best musical responses to the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina were 5th Ward Weebie’s tracks «F*** Katrina» and «What’s Your FEMA Number?» It’s also riding a new wave of interest due to the national rise of Dirty South dance rap, or crunk, popularized by Atlanta artists like Lil Jon and the Ying Yang Twins, who many local bounce artists feel borrowed a little too liberally from the New Orleans sound. (On Beyoncé’s late-2006 release B’Day, she included a bounce track, «Get Me Bodied». Performing in New Orleans at the Essence Music Festival in 2007, she apologetically introduced the song by saying, «I stole this from y’all».)

«What we’re trying to do now, people like us and 5th Ward Weebie, is reinventing bounce», says PNC’s Mr. Meana. Meana still lists bounce founders like T. Tucker, Jubilee and the Showboys as influences on his MySpace page, but musically, he’s looking to evolve. The group’s latest single, «So Attracted», which dropped in mid-July, sounds more like the national vogue in hip-hop, with a liberal use of the warble-inducing AutoTune software that gives the artist T-Pain his signature vocal sound. For Meana, it’s not the queering of bounce but it’s the appropriation by national artists like Lil Jon and the Ying Yang Twins that soured him on the sound.

«It’s been raped and stolen and called ‹crunk›, about five, six years ago», he says. «And that led a lot of people to say, to hell with it. They took our style, but now we’re gonna look like copycats.»

When the issue becomes one of national success, Miller theorizes, it gets more complicated. «If there’s going to be a town where gay rappers are going to break out, New Orleans would pretty much be the only place in the world that could happen», he says. Gotty Boi Chris agrees: «In New Orleans, they’re more accepting to homosexual music, they’ve got less prejudices.» But bounce is so specific and so locally rooted in its sound that a taint of perceived homosexuality may not be the only thing holding it back. The utter regionality, its New Orleans-ness, Miller believes, is what makes it special. The sissies’ adherence to the old-school line, too, is a big part of what keeps their fans coming back to dance.

«They’re providing music for a core New Orleans audience that wants uplifting, party dance music instead of rap that focuses on lyrical development and narrative», he says. «New Orleans people want music that keeps the vibe going – not a think-about-lyrics vibe, but a party-in-the-street vibe. And it’s still original in the wider context of rap, even as it repeats itself. It captures the energy down there (in New Orleans) the way nothing else does – a joyful, energetic, living culture.»

Freedia says that she and Katey were recently interviewed for an upcoming feature in the national music magazine XLR8R. And although PNC’s new music has been evolving, Mr. Meana acknowledges that its old hits remain surprisingly popular, especially as it reaches new fan bases. «We’ve been playing a lot of college campuses, a lot more white events», he says. «And people are acting like ‹Pump the Party› is a new song.» In the end, he feels, the distinctive New Orleans rap sound will prevail in one way or another – gay or straight, «upgraded» or not.

«Just because a song don’t have a triggerman beat, or something, doesn’t make it not bounce», he says. «Bounce is what the music is making you do.»

Visit www.blogofneworleans.com for a streaming bounce playlist featuring Big Freedia, Sissy Nobby, Katey Red, Vockah Redu, Chev off the Ave., SWA, PNC, DJ Jubilee and Gotty Boi Chris, plus others.

The Fader offers a video interview with Big Freedia: