On the Rise: The Complexities of Middle Eastern Opera

The Lebanese-American media artist, composer, and educator Joe Namy has shown a particular interest in the power structures and social constructs embedded in music. Norient spoke with him about his new project on opera and about «Libretto-o-o: d’artifice». The audiovisual work unravels Middle Eastern opera, nation-building processes, and the architecture of the opera house. «Libretto-o-o: d’artifice» is screened in the virtual exhibition «DisOrient: Welcome to the Hall of Mirrors», which is part of the German festival Mannheimer Sommer.

[Berit Schuck]: Going back in time, what triggered your interest in opera and what inspired the work «Libretto-o-o: d’artifice» that we see in the exhibition?

[Joe Namy]: The project originally started in 2016. I began looking into stalled plans for an opera house that was to be built just outside of Beirut, to be gifted and constructed by the Chinese Government, who at that time had just completed a similar opera house in Algiers, the Opera d’Algiers. I was commissioned to produce a site-specific installation loosely based on my research for the Sharjah Biennial 13 curated by Christine Tohme (Namy 2017). The commission ended up becoming a sculpture made of an operatic curtain 14 meters high and 18 meters wide, using fabrics sourced from the local fabric, souk, and draped on the outside of the Sharjah Art Museum, turning the street into a giant stage. And this sculpture was accompanied by a sound piece on the second floor of the adjacent building so you could sit and watch the street and curtain below as you listened. Photo: Installation «Libretto-o-o: A Curtain Design in the Bright Sunshine Heavy With Love» by Joe Namy, presented at Sharjah Biennial 13 (Joe Namy, 2017)

[BS]: Could you describe this sound piece a little more?

[JN]: The sound piece was a collection of five stories, poems, and testimonies from artists, composers, poets, and writers. But there was so much more material that I couldn’t incorporate, and so much more research that I wanted to dive deeper into. And I haven’t stopped diving.

[BS]: Your work «Libretto-o-o: d’artifice» demonstrates – quite literally – how your research has been unfolding since then. It comprises a video, which was shot at six opera houses throughout the Middle East, and a sonically rich soundtrack. Could you say a few words about the production of the work, which at first took the shape of a cine-performance (Namy, Lafawndah, and Aya Al-Sultani 2020) and now is a one-channel video with soundtrack?

[JN]: I decided early on to work with local arts organizations in each city1 to help me access these sites, and simultaneously organize workshops and listening sessions around the conceptual framework of the project with local artists and musicians, as a way to learn more about their relationship to these great halls. It was important to understand how artists and musicians engaged with these spaces and this history. These workshops and listening sessions informed the project. There are sounds taken from the resonant abandoned Royal Theater Marrakech recorded during a workshop we held inside the theater and there are song references taken from the history of opera in Cairo that we discussed during our workshop there. This project is much more about the process, which has been unfolding over the past four years.

[BS]: What did you select from the architecture of the opera house, and above all from the opera houses that entered your video?

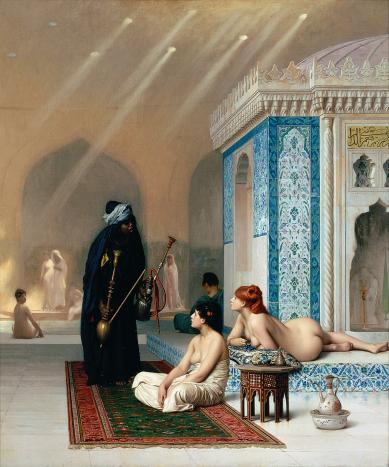

[JN]: In terms of the visual aesthetics, there are certain architectural traits that define an opera house, from the grand entrance to the proscenium, and I was interested in how these spaces were rendered, and how much of the local architectural culture and native materials were incorporated or ignored. In the case of the Royal Opera House Muscat, one of the most acoustically advanced halls in the world, you can find a mix of neo-traditional materials and design elements commonly found in new developments in the Gulf. The Tunis opera is one of only a handful of theaters in the world built in an Art Nouveau style. With the new Opera d’Algiers; it’s such a striking building in part because the design and almost all materials were entirely shipped in from China. My video work has of course its own aesthetic, which is largely inspired by Kenneth Anger’s «Eaux d’artifice» (1953), for me one of the first opera films ever made. It translates the materials of the opera house into a continuous flow of images.

[BS]: As a quick summary, I would say «Libretto-o-o: d’artifice» is a mediation on the architecture of the opera house and on the inscription of the struggle this architecture stems from (the rise of the Italian city state during the Renaissance) as well as a reflection on how all this entered the Middle East.

[JN]: I’m interested in the history and resonance of opera in the region in all its complexities. These buildings are a reflection of this cultural complexity, from colonialism to neo-liberalism. But as I mentioned before, my project is rooted in the process of looking into contemporary musicians’ and artists’ relationships to these buildings – the importance of these buildings for music, and their position and impact on the city they inhabit. From Marrakech to Muscat, these operas are absolutely tied together in a shared regional cultural narrative, but they’re also unique and come out of a complex history tied directly to their respective state-building narrative. I’m trying to unpack their legacy, how they may function within the collective memory of a nation as well as their effect on a personal level.

[BS]: You read Jacques Attali’s book on Noise (1985) early on in your research. Would you say this book has informed your research on Middle Eastern opera?

[JN]: There has been a lot written on the relationship between opera and politics throughout its history, however almost none of this addresses the impact and prominence of opera in the MENA region specifically. I was inspired by this omission. Unlike most Euro-centric narratives that are historically-centered, in the MENA region our story of opera is more contemporary (with the first opera house built in 1854 in Algiers for the French occupation). In the last ten years alone there have been six new opera halls built in Rabat, Algiers, Dubai, Muscat, and Manama; I’m trying to figure out why that is.

[BS]: And what can you say so far?

[JN]: Part of the reason is tied to the fashionable trend of those in power establishing their permanence through architecture, and the opulence and pageantry of opera lends itself very nicely to the kinds of power mythology and high culture those in power are trying to establish. In the case of Beirut and Algiers, you have geo-politics playing out through soft power, with gifted opera houses entirely designed and built by the Chinese, tied to larger construction packages under the Belt and Roads initiative and real estate developments. Also because of this connection between power and culture, these theaters are often seen as symbols of the state, and so when you have major protests or revolution, these buildings become charged spaces, especially in the case of Cairo, Tunis, and Beirut, where the opera house provided one of the major protests sites and still continues to serve as an icon for the struggle today. I find the story behind these spaces and their relationship to the cities they inhabit so fascinating.

- 1. In Marrakech, Joe Namy worked with Le18, a.r.i.a. in Algiers, Townhouse Gallery in Cairo, the British Arts Council in Oman, and he received generous support from the Sharjah Art Foundation Production Programme to help make this all possible.

List of References

This interview has been made in the context of «DisOrient: Welcome to the Hall of Mirrors». A virtual music video exhibition by Norient for Mannheimer Sommer (July 12–22, 2020). Because of the Corona pandemic, the festival took place as a virtual event.

Biography

Links

Published on June 23, 2020

Last updated on August 24, 2020

Topics

Place remains important. Either for traditional minorities such as the Chinese Lisu or hyper-connected techno producers.

Why do people in Karachi yell rather than talk and how does the sound of Dakar or Luanda affect music production?

How did the internet change the power dynamic in global music? How does Egyptian hip hop attempt to articulate truth to power?

Special

Snap