How to Make a Soundscape Film

The soundscape of a film defines its perception, yet it is often neglected. While watching RIAFN, a cinematic journey into the soundscape of the Alps, our writer decided to write a short guide to making a soundscape documentary, in five steps.

A soundscape documentary film is a kind of a cinematic journey through the sounds of a certain region. While a region may be visually recognisable, nature itself rarely has a characteristic sound. It is man- or animal-made noises that give a region its typical sound. Documenting these representative sounds, in combination with pictures, can be extremely mesmerizing if it’s done well. But the key to a soundscape documentary is a great arc of suspense. The question is how to create such an arc, even though a documentary doesn’t tell a story. The following five-point guide aims to offer a response to this question.

1. Material

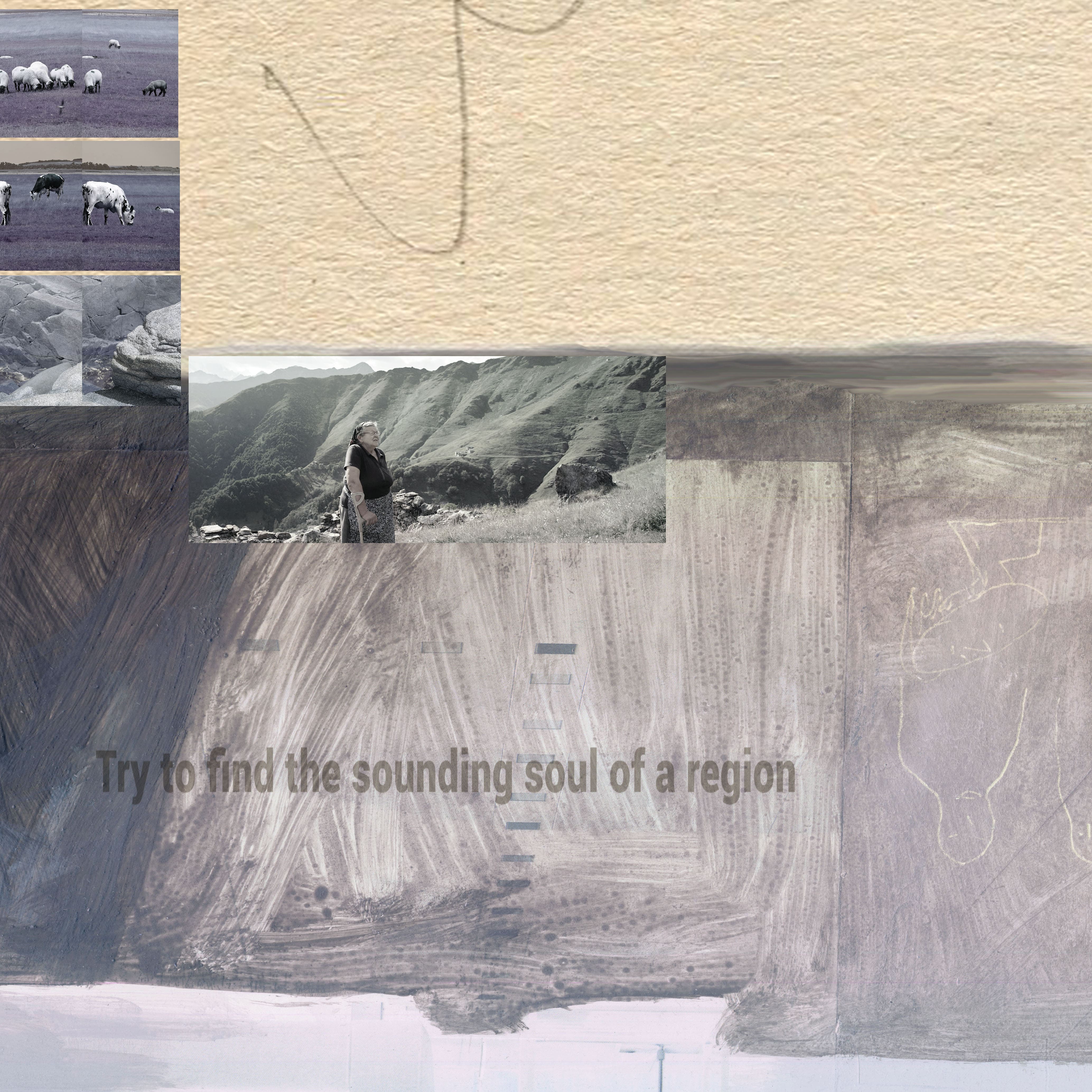

You need footage and sound recordings. Everything depends on how valuable your material is. Valuable material is authentic material. This isn’t about the virtuosity of the man-made sounds. Virtuosity became boring in the 21st century: The arts reached an incredibly high technical level and skills are outstanding in each art form. This leads to oversaturation. So pay attention to rare, earthy, and lusty sounds rather than sophisticated or complex ones. Try to find the sounding soul of a certain region.

2. Spatiality and Reverberation

You may not need a great variety of different sounds, but you need the greatest possible variety of different spaces: Close miking, distant miking, ambience recordings. Catch every sound with different reverberations and every picture from different angles and perspectives. This gives you maximum editing options.

3. Manipulation and Transformation

Be careful with sound editing. Of course you can enhance your recordings to a certain extent. But sound manipulation leads quickly to alienation. If drastically changed, the sounds lose their genuineness and their connection with the visuals. Transformation and manipulation are artistic tools. Use them sparsely in a documentary.

4. Pulse and Rhythm

Try to find a pulse for your film. Be aware of the relation between the cutting rhythm and the rhythm of the recorded sounds. Use rhythms when they occur. Any kind of machine produces rhythm; or a walking herd of cows, for example, produces a phenomenal bell rhythm. Create rhythm in certain sections by combining sound files.

5. Compression and Interlocking

A movie isn’t an image of a situation but a portrayal. Never try to transfer the situation one-to-one with your camera and the microphone. Sitting in the cinema auditorium, the spectators of your film are in a completely different situation than you are out in the field. Therefore their perception is completely different. The silence of the Mongolian steppe, for example, is a stunning experience, but you can’t reproduce that by raising your mike and recording nothing.

Let It Overlap

In a documentary you must retell your experiences and observations by other means. Compress and interlock your sound and video material, let it overlap and merge. Draw up a musical score for your sounds and take into account silence, loudness, intensity, pace, tempo, and range of sounds.

Following these five steps doesn’t guarantee that you will create a great movie, just as reading a composition instruction book doesn’t guarantee that you will compose a great symphony. But thinking about these points may bring you to other results when making a film. Most of all, it may show you a different perspective, or give you greater enjoyment, if you are watching a soundscape documentary.

Biography

Published on November 20, 2021

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topics

How do acoustic environments affect human life? In which way can a city entail sounds of repression?

What is «Treble Culture»? How does what one hears affect what one sees?

Snap