Italy might be 9,000 kilometers away from South-Korea and yet, K-pop has reached its shores nonetheless. NTS Radio-affiliated Paola Laforgia reflects on the reason behind its popularity both inside and outside of the peninsula, and wonders what the future of music in a globalized world could look like.

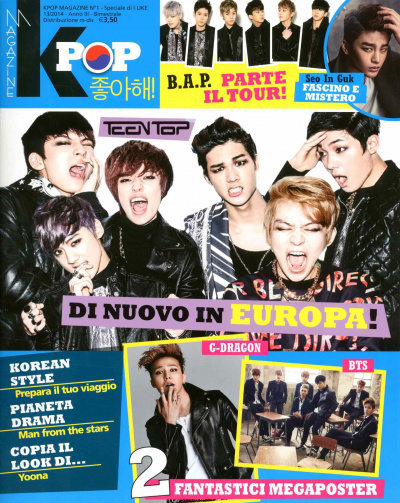

In April 2014, renowned Italian publisher Panini released Italy’s first ever magazine dedicated entirely to K-pop. Simply titled K-pop Magazine and aimed mainly at a female teenage audience (along the lines of its most popular publication Cioè), the bimonthly sought to be the go-to periodical in the Italian language for all things Korean pop culture — «the phenomenon of the moment» in the words of Panini’s press release (AnimeClick 2014) — from music to K-dramas, to celebrity gossip and fashion. The magazine, however, was very short-lived. After only four issues it ceased to be published, and today, not even a trace of it is left on Panini’s official website. What went wrong?

In Italy, K-pop has not saturated culture as quickly and widely as it has in the U.S. or other European countries such as France, Germany, and the U.K. This fact is clearly visible when comparing the respective music charts, how high the trending hashtags rank on Twitter, or the number of concerts and events held in each of these countries.

And yet, it is not as if highly engaged Italian fans are nowhere to be found. Let’s not forget that back in 2012, the boy-band BIGBANG won the award for the «Best Fan» category (and notably were the first Asian act to do so) at the MTV TRL Italy Awards. Since then, the community of fans has kept growing every day. Social media is populated by Italian fan accounts: At the time this article was last reviewed in late January 2021, the hashtag #kpopitalia had 13.8 million views on TikTok and 141 thousand related posts on Instagram. For those who argue social media analytics do not reflect reality, here is a video of the crowd that filled Milan’s iconic Piazza del Duomo in March 2019 to dance to K-pop songs.

K-pop fans gathering in Piazza del Duomo, Milan to dance together to popular K-pop songs. «GoToe K-pop Random Play Dance» has been held in cities all over the world.

The Time Is Ripe?

Back in 2014 when the magazine was launched, Panini clearly noticed an opportunity to tap into a not yet fully targeted and apparently growing share of the market. Regardless, the magazine was a flop, and a quick scroll through comments on social media, blogs, and specialist websites reveals why. It was not because a target audience for it was missing, but because such an audience felt it offered nothing «[…] that is not already available on the internet» (AnimeClick 2014).

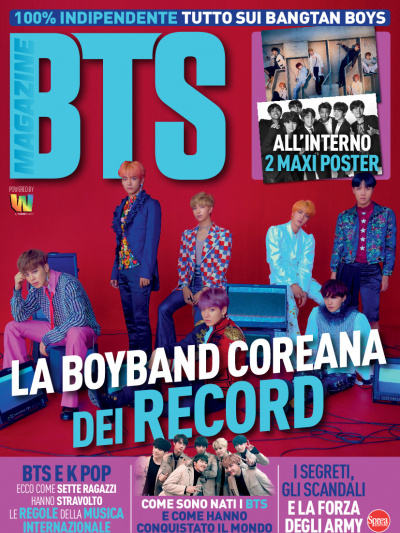

Nevertheless, in June 2020 rival publishing house Sprea tried its luck and launched a special 80-page magazine dedicated entirely to the most popular K-pop band of all time, BTS. «The time is ripe», they must have thought. BTS fans in Italy have been estimated to be in the tens of thousands (Yonhap News Agency 2020) and fans tend to crave collectibles. Even the key South Korean news agency Yonhap reported the news this time (ibid.). However, a couple of Italian media sources mention that the magazine was not supposed to be a one-off, rather a bi-monthly, but no other issues have seen the light of day.

Cultural Flows

As we all know, in recent years, access to the world wide web has become more and more affordable and widespread, social media has proliferated, and we have witnessed the steep collapse of print publications (Ember and Grynbaum 2017). We might be led and misled by algorithms, yet it is also undeniable that we are indeed «exposed to a wide range of voices», that there is a variety of «cultural goods on offer» (Hesmondhalgh 2015, 88–89) from which we can choose. And the algorithm itself, especially on platforms like TikTok, can actually help us connect with a community which shares our interests, that we might have had a hard time finding in real life. This means it is relatively straightforward for an Italian, especially a young one, in 2014 and even more so in 2021, to stumble upon K-pop while casually surfing the internet, get fascinated by it, start following it regularly, and join a virtual tribe of fellow fans – all without the aid or nudge of the traditional mass media.

Some may wonder how a bridge can be built between two faraway countries, both geographically and culturally, such as Italy and South Korea: Two countries that are also relatively peripheral in the scheme of the international cultural trade, usually dominated by the U.S. and to a lesser extent by the U.K. However, cultural flows are much more complex and contradictory than they might seem at first glance, and today it is definitely «no longer possible to portray the global cultural system as one in which the countries of the West impose[d] their cultures on the non-West» (ibid. 275). As a result of the increased interconnectedness of the world thanks to the internet, but also to faster transportation and migrations, cultural identities are becoming more complex and less rooted in a specific nation. Many cultural products are now catered not to a particular country, but to «groups of people who share a transnational culture across different national spaces» (ibid. 277) — think diasporic groups or more abstractly people who share a taste in a particular cultural expression, like in this case K-pop.

KBS World, the international broadcasting service of KBS, South Korea’s national public broadcaster, reports about the 2016 edition of K-Pop World Festival Global Audition held in a number of countries including Italy.

Soft Power and the K-Wave

The pivotal role the South-Korean governments have played in the development of its cultural industries should not be overlooked. From the early 1990s onwards, such industries have been regarded as central to the nation’s «export-focused economic development strategies» (Kwon and Kim 2013), and policies around them have drastically changed from ones of censorship and political control to ones aimed at facilitating their growth: For instance low-interest loans, preferential taxes, and public provision of infrastructure. In addition to this, there is also the recognition of the perks of soft-power – that is to say, how culture can be used as a tool to attract and appeal, to influence the behavior of others, by co-opting them rather than coercing them (Nye 2004). Let’s just look at tourism data for instance: The number of foreign tourists visiting South-Korea has increased nearly fourfold from 300,000 in 1998, when the Korean Wave began, to 11.8 million in 2014 (Bae et al. 2017). Not by chance, in 2017 BTS was nominated Honorary Tourism Ambassador for Seoul city.

There are a number of Korean Cultural Centers (KCC) around the world whose job is to promote Korean culture and facilitate cultural exchange. These are non-profit institutions that are aligned and work together with the Korean government. They offer language courses, hold talks and events, and also a «K-pop Academy». The 2019 edition at the KCC in Rome seemed to have been a success.

In Conclusion

In consumer culture, the consumption of particular cultural products is not merely consumption but a meaningful way to express and build a certain identity. By listening to K-pop, Italian fans feel part of a wider community that transcends the national borders of the country they primarily identify with. Such identification is possible for a number of reasons. First of all, one might argue that K-pop, in the same way as other contemporary local popular musics, is «the result of complex reinterpretations of imported styles and technologies» (Hesmondhalgh 2017, 302), and therefore it is rich in recognizable Western musical elements, which of course are integrated and reinterpreted in a new way, but still evident enough for a new listener to not be completely overwhelmed by the novelty of it. On the other hand, however, it still comes across as new and different from the Western mainstream music scene (first of all, of course, because of the language), and precisely for this reason it has huge appeal. K-pop might be the equivalent of the Western mainstream music scene in its own South Korea, but in the West the K-pop community has the characteristics of a subculture. K-pop is an alternative, it is almost underground.

In addition to this, contemporary consumption practices (see for example social media) enable people to create tribes formed not rigidly along traditional structural determinants (e.g. nationality, class, gender, religion), but built around a certain «state of mind», a «lifestyle», hence allowing the construction of a more fluid identity (Anderton, Dubber, and James 2013, 149), and facilitating having multiple cultural identifications at the same time. It does not matter if one fan is a 17-year-old from a tiny village in the Italian alps, and another one is 28 and from Jakarta, Indonesia. Both will have in common their love for a particular K-pop band and that will be enough for them to bond and feel similar.

And then of course there is the language issue. We should not forget that to the Italian ears, the English language is of course more common and widespread than Korean. It shares more similarities with Italian, but it is still a foreign language, and one in which not many Italians are perfectly fluent. In fact, the Italian fandom community relies on unofficial fan translations into Italian of the English subtitles available for most of the K-pop content on the web. Therefore, whether the music is in English or Korean, the language barrier will be present in both cases. Why then would Italians have more reasons to choose English over Korean? Either way, it is not their native language. Either way, the language barrier has not proved to hinder a connection to the music. Otherwise, we would not be able to explain why the non-English speaking world is able to enjoy English-sung music.

K-pop creators seem to know all this very well and will continue pursuing their «conquest of the West». Italy might still have to wait a little longer to see the most popular K-pop bands perform within its borders (which has already happened in neighboring France and Germany). However, the fact that the song «Dynamite» by BTS was the first K-pop song to be certified platinum in Italy as of January 2021 (Cicciotti 2021), and was introduced to the wider public through the Italian version of the Samsung Galaxy S20 FE TV commercial for which it was the soundtrack, as well as through two performances on two different mainstream Italian TV shows (Ballando con le stelle and Amici) in October 2020 and January 2021 respectively, can raise fans’ hopes. Indeed the TV newscast of the main Italian public TV channel, TG1, does not shy away anymore from reporting on the K-pop universe – a signal not to be underestimated.

Italian state-owned TV channel Rai 1’s news program TG1 report on K-pop band BTS, July 7, 2020.

As new cultural industries emerge and new technologies are introduced, new relations between distant places will definitely form (Hesmondhalgh 2015, 307–8), and the rulers and the ruled will sooner or later swap roles.