Taqwacore: Punk Polyculturalism

Taqwacore combines alternative interpretations of Islam with a punk anti-status-quo ethos, probably best known through the U.S. band The Kominas. Dusting off Wendy Hsu's dissertation chapter on artists-led struggles for justice and resistance against Islamophobia and anti-immigrant racism, this Norient four-part series deals with the band's experiences as brown-identified, South Asian Americans living in the midst of hate and fear – and could inspire creative dissent and resistance in the near future.

Introduction

I remember the day I sat down with the Taqwacore band The Kominas for the first time at a diner near South Station in Boston back in 2009. For four hours, members of the band ushered me into the political vortex surrounding their existence. These musicians not only changed the course of my dissertation research. They changed my outlook on the potentials of music in creating social change. They generously shared their experiences as brown-identified, South Asian Americans, living with compassion and love in the midst of hate and fear. The Kominas helped me discern nuances within the liberal and conservative shades of Islamophobia and the murky racial politics surrounding minoritarian post 9/11 identities. Above all, their words and music embody much strength and community love and fuel my sense of justice. Now in 2017, some things have changed but others haven’t. The term Taqwacore has diffused into the cultural ether. Some of the affiliates are still making music but others have moved onto other projects. We have come a full circle to another repressive regime with the new presidency in the United States. The recent history of the culture of hate and fear is more present than ever.

The Kominas, a South Asian American rock band spawned in the suburbs of Boston, is well-known for its association with the grassroots music culture self-labeled as taqwacore. The prefix «taqwa» is a Qur’anic Arabic term meaning «fear-inspired love» or «love-based fear» for the divine. The suffix «core» refers to the punk roots highlighting the do-it-yourself ideology and subversive attitudes central in hardcore punk music scenes. Taqwacore is conceived to reclaim a space for an alternative practice of Islam inflected with the punk anti-status-quo ethos.

Michael Muhammad Knight coined the term in his novel The Taqwacores, a fictional account of a group of college-aged individuals who live in a house together in Buffalo, New York. Each character in the novel maintains a unique lifestyle and a host of ideologies that question orthodox Islam and reinvents the meaning and practice of Islam for him or herself. After the book’s publication, Knight used social media and email to reach out to various punk rockers of Muslim heritage living in North America, forming a network of friends, artists, bloggers, filmmakers, and other enthusiasts around the self-identified label of taqwacore. In this four-part series, I trace the socio-musical experiences of the Kominas through the lens of U.S. racial dynamics, with a focus on how the members of the band navigate themselves as racial and religious minorities in the post-9/11 sociopolitical terrain. In particular, I situate the band’s experiences in two disparate political contexts: the socially conservative U.S. during the George W. Bush administration and the ostensibly liberal terrain crowded by non-Muslim hipsters, indie-rockers, and other multiculturalists.

Anti-Muslim Policies and Liberal Appropriation of Islamic Counter-Culture

Part 1 focuses on the band’s questioning of the conservative anti-Muslim policies and practices. Part 2 foregrounds the band’s challenges against the liberal appropriation of Islamic counter-culture and strategic interventions in liberal and consumerist multiculturalism. Refusing to be boxed in by the category of «Muslim» or «American», «immigrant» or «citizen», members of The Kominas defies consumerist objectification and categorization. Using taqwacore to reframe the ideology of cultural difference to focus on a collective struggle for social justice, the band take a polyculturalist (Prashad 2001) approach in forging solidarity with other racial and religious minority groups.

Part 3 features a close reading of a performance that illustrates the anti-status-quo concept of taqwacore within and around the American Muslim experience. In the final and fourth part of the series, I discuss the band’s articulation of a brown-and-punk identity that the band has forged in solidarity with Latino/a immigrants. The Kominas transforms multiculturalist thinking to mobilize minoritarian politics. This critique ultimately points at the political contradiction between conservative and liberal United States to reveal an underlying race-based logic that is shared by both ends of the political spectrum. Finally, a note about my relationship to this research project. Interpreting sounds and sights of The Kominas’ performance life while participating in the scene as a music blogger and event organizer, I learned the complexities of what Islam means to each of the band members and their taqwacore associates, particularly in the shadow of race after 9/11.

This article is meant as a way to open up the meanings of Islam in a pluralistic fashion. As a cultural outsider, I recount the musicians’ words and experiences of the Muslim heritage and Islamic faith, not with the intention of placing their religiosity into binary categories of «Muslim» or «non-Muslim». Instead, I consider each instance of discussion about or performance related to taqwacore, punk, and Islam, however contradictory it may seem, a productive tension. It is precisely this productive tension that has facilitated the emergence of this complex cultural space known as taqwacore.

Playing in the Midst of Post-9/11 Green Menace

With fans and musician friends, The Kominas were touring the U.S. the summer of 2009. To save travel expenses on their cross-country, 15-city tour, the band drove a hybrid Honda Accord while towing a trailer. In the parking lot at The Bridge PAI, a local arts space where I was hosting The Kominas’ performance in Charlottesville, I stood mesmerized by their silver boxy 5‘ x 8’ trailer, decorated with myriad stencils, stickers, drawings, and scribbles, contributed by the band and its cohort. These messages of inside jokes and symbols of idealism readily expressed aspects of their D.I.Y. Bohemian lifestyle, in solidarity over shared passion and alienation. Admiring the art on the trailer, I saw an inter-faith equation expressed as the following: «Allah= Love, Jesus = Love, Yhwh= Love».

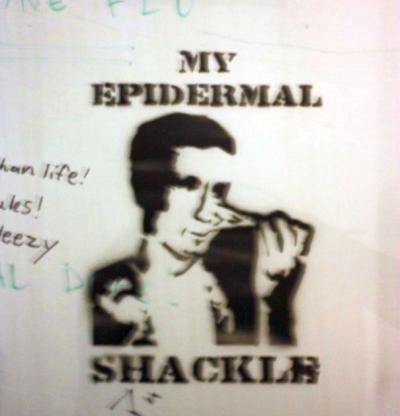

One black stencil mark, with a figure of a man pulling his facial skin, read, «My epidermal shackle» [Figure 1], a lyric from a song written by Omar Waqar, also on tour as Sarmust. Omar had been friends with the members of The Kominas since the «Taqwatour» two years ago in 2007. Standing next to the trailer, Shahj (Shahjehan) recounted to me some of their tour adventures. The story of a racist encounter at a gas station on their way from Atlanta to Virginia struck me the most. A few white American men accosted the band members if their trailer was where they «keep all of (their) hate mail. Shahj told them that they were a band. The group of men replied, «Oh, that’s cool». Apparently, their animosity diminished after they found out that The Kominas was a group of musicians. How bizarre. Shahj revealed that he felt as if this interaction was race-related. But he expressed that he didn’t really understand the usage of the term «hate-mail». I thought to myself: Could this be an instance of the «epidermal shackle»? Punk anarchy is only «cool» and non-threatening, as long as it’s not related to people who appear to look Muslim, brown, or like a terrorist or an immigrant.

Six weeks after September 11th, the United States government implemented The U.S.A. Patriot Act with the intention to eliminate terrorism and «unite and strengthen America» (U.S. Senate 2001). This act has mobilized laws to enforce the surveillance of terror-related activities. To enact The Patriot Act, law enforcement, military, and intelligence service officers deployed intense surveillance upon non-citizens, immigrants, and individuals of any Muslim, South Asian, and Arab affiliations. A broad range of anti-Muslim exclusions such as racial profiling and hate crimes occurred. Mass detentions and deportations of Muslim and Arab American men as well as «Special Registration’ program requiring Muslim immigrant men to register with the government and submit to questioning» (Maira 2009, 12) took place beneath mainstream media visibility. Vijay Prashad links the post-9/11 condition to McCarthyism during the Cold War. Not a Red Scare, but a «Green Menace». This time, the enemy is Islam. Prashad observes, «All Muslims are suspects by association, but those who had come into even fleeting contact with the organs of Islamic radicalism are fair game for arrest and interrogation. Like McCarthyism, the main agent for social oppression is not the state, but it is private institutions and our neighbors» (2003, 72).

Basim Usmani, the bassist of The Kominas, is not a stranger to this feeling. He enacts this post-9/11 state of paranoia in his song «Sharia Law of the USA». In the studio recording of the song, a looming sense of a war-bound dystopia is created by audio samples from the civil defense films formerly used as public education during the Cold War era in the 1950s. The first sample occurs at the end of the instrumental introduction, following a sustained guitar feedback siren and a bomb-like strike. The musical bomb coincides with a large explosive sound in the civil film audio clip. The announcer admonishes, «Emergency: The United States is under nuclear attack. Take cover immediately in your area’s fallout shelters». Short snippets of another 1951 civil defense audio clip emerge in the mix. These segments are sampled from «Duck and Cover», a wartime cartoon that was used to instruct children to «duck and cover» in the event of an atom bomb attack. Near the end of the section, the instrumental sounds recede and the 1950s announcer’s voice resounds in the foreground of the mix, «It’s a bomb! Duck and cover»!

Racial Profiling of Islam Identity

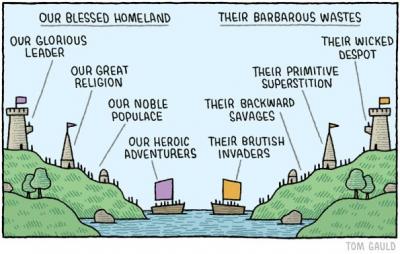

The racial profiling in the scheme of Homeland Security and other political attention on Islam and Muslim identity, after the events of 9/11, has reorganized racial dynamics in the United States. Sunaina Maira observes that «The primary fault lines are no longer just between those racialized as white Americans versus people of color, or even black versus white Americans, but between those categorized as Muslim/non-Muslim, Arab/non-Arab, and citizen/non-citizen» (2009, 232). In this environment, marginalized identities such as Muslim, Arab, immigrant, and South Asian are often conflated and jumbled up into one ambiguously generalized threat. This recently otherized entity is oftentimes found demonized, romanticized, or fictionalized in press media. In what follows, I will attempt to tease out how this us-versus-them racial binary has seeped through the media discourse surrounding taqwacore and The Kominas, while highlighting the band’s critical response.

Media outlets have preyed on the band’s connection to Islam as a cultural novelty. The press reinvented the notion of taqwacore as «Muslim punk», without delving into the complex inter-ethnic relations and the community’s ambivalence to religion and culture. Over beers and French fries at the South Street Diner, a few blocks away from the South Station in Boston, members of The Kominas shared their frustration with me. They complained about the rampant deployment of shallow, essentialist notions by media sensationalists. Shahjehan explained: «We got to do a lot of cool stuff because of the novelty aspects of it, because of all the media shit. But it’s difficult when that stuff happens right away, then you wonder if people are actually interested in it musically. Because a lot of songs on that album are pretty damned good songs, but if this whole other aspect to it wasn’t there, you know like the Muslim, post-9/11 crap or whatever. People ask what taqwacore is. It’s nothing more than a few kids that talk online. People think it’s like this thing where we all hang out, we all sit around in this house» (2009).

Since the formation of the band in 2006, mainstream media, music and non-music-related, has hovered around the existence of The Kominas while pigeonholing members, friends, and fans of the band. Shahjehan’s grievance begins to elucidate the race-inflected sensationalism of the Islamic religion in the media after 9/11. The Kominas’ cynicism is not unfounded. The media has appropriated the image of the band and their associates under the banner of taqwacore for various rhetorical and political agendas. Mainstream press has exaggerated The Kominas’ affiliations to Islam. An article on CNN.com claims that three of the four members of the band «identify as Muslim – both practicing and non-practicing» (Ansari 2009). Out of annoyance and frustration, Basim sent a message to all his followers on Twitter, «That's funny. I told CNN we were three atheists and one Muslim, and they flipped it» (Usmani 2009). While Basim identifies with the anti-status-quo spirit of the taqwacore concept, he finds the mass-media-invented term «Muslim punk» repulsive.

«Slam-Dancing to Allah»

In an interview, he denounces the sensationalizing or «sexy» effect of «Muslim punk» in Western media (Rashid, et al. 2009). Media attraction to the idea of «Muslim punk» is based on an assumed contradiction within the term, a contradiction that would only make sense outside of the Muslim (as well as South Asian and Arab) communities. Mainstream media capitalizes on this opposition in order to sensationalize headlines such as: «Allah, Amps, and Anarchy» in Rolling Stone Magazine (Serpick 2007); Newsweek’s «Slam-Dancing to Allah» (Philips 2007); «Nevermind the Islam. The Kominas Are Punk» in the L.A. Times (Abdulrahim 2009); and in the U.K. newspaper The Sun, «Never Mind the Burkas: Rockin’…Kominas in Boston at the Sad Cafe in Lowell» (Iggulden 2007).

The presumed irreconcilability between Islam and punk, I argue, is predicated upon the notion that punk music is «Western», white, or American. Alan Waters, an anthropology professor at University of Massachusetts-Boston, makes this very assertion in the Associated Press’ story about The Kominas and other taqwacore-related bands. He said, «Punk rock is very American, and this is assimilation through a back door» (Contreras 2010). This assertion runs the risk of cultural chauvinism because it lays claims on the social practice of playing rock music as being «American». This view not only ignores the historical British roots of punk rock (and its influences from West Indian immigrants in England). It also dangerously reinforces the Orientalist binary between «American» and «Muslim». But how could a band that plays songs about suicide-bombing the Gap and instigating the Islamic Sharia Law in the United States be assimilationist? Neither Waters nor the Associated Press writer attempts to resolve this tension. In fact, no press has paid any serious attention to the band’s music. What The Kominas, along with its taqwacore associates, calls for is a middle space that allows for a critical intervention in this raciailized us-versus-them rhetoric. This cultural space is vital for the production of alternative understanding, practices, identities, and relationships to and around Islam.

A Reinterpretation of Islam?

It is a discursive space where one could be critical of Islamophobia without being labeled as Islamicist or un-American. It resists rhetorical simplifications and flattening. Borrowing from the anti-authority punk ethos, this cultural space could contribute to a reinterpretation of Islam and U.S. racial dynamics. Just because one castigates the United States foreign and domestic policies doesn’t mean that he or she is a non-citizen or a Muslim terrorist. On the flipside, just because one has a Muslim heritage doesn't mean that they represents the entire Muslim community and is necessarily an enemy of the state.

With a title similar to the Sex Pistols’ «Anarchy in the UK», the song «Sharia Law in the USA» evokes the now-classic English punk band’s anti-status-quo punk ethos. The song begins with similar lyrics: «I’m an Islamist; I’m the anti-christ», but with less seriousness. Sprightly finger-snapping accompanies the syncopated vocal lines sung with a smooth vibrato. Basim sings these lyrics in the style of doo-wop or Broadway show tunes. His suave delivery elicits an irony between the lines of menacing words. This is not a serious message of hate or threat. The stylistic shuffling between punk raucousness and American show-tune urbanity creates an ironic distance that thwarts the absolutist ethnic and religious ideologies embedded in the surveillance rhetoric.

Masters of punk irony, The Kominas parodies the stereotypical depictions of Muslim, South Asian, and Arab masculinity produced by post-9/11 media. With wit and irony, the vocalist subverts while embracing the menacing image of Muslim masculinity. Juxtaposing Sharia Law as a symbol of Islamic fundamentalism with the unexpected context of the anti-status-quo practice of punk anarchy, this song is blasphemous to both fundamentalist Islam and to the anti-Muslim Bush administration. Singing, shouting, and slam-dancing, The Kominas highlights the absurdity of U.S. homeland security policies, at the same time undercuts authoritarian and fundamentalist forms of Islam. This double-edge critique cuts through the ethno-religious binary between US and Islam, or «American» and «Muslim». This ideological binary underpins the epidermal shackles-echoing Omar’s words-affecting South Asian and Arab Americans.

Problems of the Civilizational Rhetoric

On the main drag in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, groups of 20-somethings parade under the intense August sun. Sporting a hipster style en masse, they were all wearing dark-framed «nerdy» glasses, old t-shirts, skinny jeans, slip-on canvas shoes, and other accessories salvaged from thrift stores or purchased at a local Urban Outfitters chain store. Uniform multicolored checkered scarves wrap around their necks and shoulders. Without a checkered scarf, I stuck out like a sore thumb. Or maybe it had less to do to with the scarf, but more with the wearer of the scarf or the ethnicity of the wearer of the scarf.

Known as «kufiya» (conventional spelling «keffiyeh»), this piece of «ethnic» fabric represents a vague notion of resistance, but only as a sartorial device that displays a fashionable statement within hipsterdom. Formerly worn by rural Arab peasant class in Palestine, the keffiyeh became a symbol of nationalist resistance during the 1930s Arab revolt in Palestine and later became absorbed into European-American leftist couture, as well as street and commercial fashion in the United States since the 1980s. In the mid to late 2000s, the majority of the keffiyeh-clad individuals are typically either unaware or only vaguely familiar with its pro-Palestinian, anti-war associations (Swedenburg 2010). Collectively worn by hipsters, these keffiyehs say one thing: the new hip couture is a piece of the ethnically other «Islamic» world.

In Adbuster, a magazine with interests in anti-commercial and environmentalist interests, Douglas Haddow comments on the commodification of keffiyeh. He claims that the keffiyeh has «become a completely meaningless hipster cliché fashion accessory» (2008). What intrigues me is the title of the article: «Hipster: the Dead End of Western Civilization». Unwittingly, Haddow’s rhetoric resonates with the «civilizational» discourse that Samuel Huntington used in his well-known, polemical theory of the «clash of civilizations» (1996). In the wake of the events on September 11, 2001, George W. Bush deployed the language of civilization in his declaration of the War against Terror. «This is civilization’s fight», Bush says, is presumably a fight against the «uncivilized non-West» (Palumbo-Liu 2002, 109). This rhetoric reinforces a binary that is rooted in religious, geographical, and ideological differences here and there, «America» and the Terrorist-spawned «Islamic» world, and between «us» and «them».

Haddow has no interest in Bush’s right-wing project for constructing an imperial West. His critique instead points at the contemporary alternative, leftist stream that is tied to the so-called «Western counterculture». He denigrates hipsters for their perpetual consumption habits and apolitical ethos by comparing them with previous Western countercultural movements. Haddow’s critique of hipsterdom is class-based. He targets the fashion and culture industry for its ravenous appetite to commodify hipster desirables. He also castigates an uncritical complicity on the part of the hipsters themselves. I sense an uneasy dissonance in Haddow’s juxtaposition of an «Islamic» symbol and the failure of «Western civilization». Are all hipsters necessarily «Westerners»? What is it like to be a minority within this scene that readily consumes Palestinian or more generally, Islamic imagery as a «cultural» wearable? Unfortunately, Haddow’s assessment overlooks the racial and ethnic dimensions of this cultural phenomenon. The consumerist orientation toward ethnic symbols within hipster culture shows the Eurocentrism and whiteness underlying the ostensibly welcoming, multiculturalist hipsterdom.

Critiquing Multiculturalism

At the South Street Diner, I found out that guitarist Arjun and drummer Karna are not of Muslim background. Arjun informed me that he and his brother are of Indian Bengali descent and their mother is Hindu. Their non-Muslim heritage is often overlooked in the press. Occasionally this difference is subsumed under the multiculturalist banner of «diversity». Rolling Stone Magazine’s article describes them as «Hindu dudes», implying a status peripheral to the «Muslim» members. During my interview, Arjun said, «we would always find our points ignored and our «diversity» noted as some kind of brownie badge on the Kominas label. «Fuck that» (Khan, et al. 2009). He spoke about the «cuddly» effects of the multiculturalism intended by liberal press. «The thing is that they use me and Karna to make the whole thing a little cuddly because it’s diversified. «Oh there’s a black dude in the band». Dan. «Oh there’s two Bengali Hindus in the band». «Holy shit these Muslims must be really cool. They are all accepting. This brand of Islam, this revolution they’re pushing for, this is it. This is what’s going to change the religion». «We’re not even a fucking part of that religion» (Khan, et al. 2009).

Arjun’s remark about The Kominas’ «diversified» interethnic and inter-religious membership resonates with Maira’s (2009) observation of the absorption of «Islam as a marker of cultural difference». This cultural process is structured by the logic of multiculturalism and is driven by the ideal of «expand(ing) the rainbow spectrum of diversity» (Maira 2009, 228). It in turn depoliticizes the racial ideologies that govern the exclusion and marginalization of individuals of Muslim, South Asian, and Arab heritage in the United States. Anthropologist Shalini Shankar (2008) notes that the diversity agenda assimilates and displays racial differences while effacing the reality of racism.

«This norm of Whiteness is one on which multiculturalism is premised» (Shankar 2008, 122). Moreover, the celebratory, pro-diversity interpretation of The Kominas positions the band as being «cool» for supposedly promoting a progressive «brand of Islam». The ideological undertone is a binary that distinguishes between «good Muslims» versus the «bad Muslims». This binary demonizes those who are supposedly responsible for terrorism (Mamdani 2004, 15; cited in Maira 2009, 235); at the same time, it claims those non-threatening Muslims as acceptable for practicing good (US American) liberal multiculturalism.

The Kominas refuses to be subsumed under the U.S. rainbow of «good» ethnic minorities. With a name that means «scumbags» in Punjabi and Urdu, The Kominas does not pretend to be exemplary Muslims in accords with any religious and social orthodoxy. Playing on the images of the «bad Muslim», while embracing the abject, a definitively punk ethos, the band enlists Terrorist metaphors in its songs: «Suicide Bomb the Gap», «Sharia Law in the USA» and «WalQueda Superstore». Instead of a liberal consumerist or a feel-good, apolitical version of U.S. multiculturalism, The Kominas exemplifies a kind of critical pluralism. The band challenges the racial status-quo and builds solidarity across various social lines. Acutely aware of the politics of assimilation, The Kominas play with the symbolic meaning of ethnic garments in their visual materials.

Critical Pluralism and a Dissenting Polyculturalism

The Kominas’s critical pluralism is embodied by the band’s visual performance in a photograph taken by documentary photographer Kim Badawi. This photo displays three members of band, each accessorized by a garment that is symbolic of the culture of Islam. On the left, drummer Imran Malik unfolds the layers of his dark blue and gray keffiyeh. In the middle, guitarist Arjun Ray wears a burgundy and white keffiyeh around his neck, while holding a cigarette in his right hand. Arjun stands tall with confidence. To his right is guitarist Shahjehan, with a tightly trimmed goatee, wearing a crimson color short-sleeved kurta (traditional male tunic in South Asia) with detailed gold-threaded embroidery. His attire renders him looking excessively ethnic. Without shoes, he stands nervously. Relative to his bandmates, Shahjehan’s presentation exudes discomfort.

I read Shahjehan’s performed otherness an expression of the unassimilated, of the immigrant. This performed discomfort instantiates Muñoz’s conception of «disidentification», a dynamic cultural process that breaks down and rebuilds a cultural text to perform two opposing but related functions (1999). Shahjehan’s sartorial performance recontextualizes an unassimilated immigrant, a symbol of marginality that is un-hip by the consumerist hipster standard. It at once unveils the exclusionary hipster practice of wearing a keffiyeh; and in doing so, «recircuits its workings to account for, include, and empower» immigrant identities and identifications (Muñoz 1999, 31). Staged for a critical effect, this photo as a whole displays tension with regards to the cultural meaning of keffiyeh. Juxtaposing the keffiyeh and the kurta as a way to undercut a hipster fashion orthodoxy, the three actors, in combination, expose the constructedness of the value of hipness associated with the scarf. This photograph reveals the contradictions of the seemingly progressive liberalism embedded in this ethnic chic.

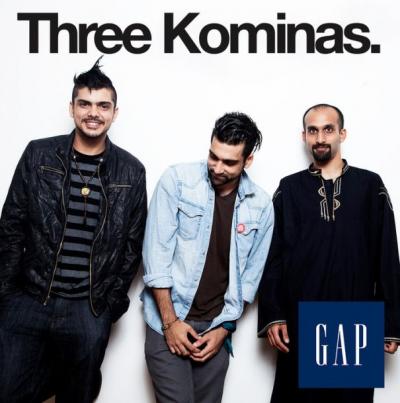

Staging for theatrical effects, the band made a mock advertisement for The Gap clothing company and shared it through their social media channels. This photos displays three members of the band. Bassist Basim standing on the left wear a tall mulhwak and a black leather jacket. With a clean punk rock style, Basim confidently looks into the camera with a bright smile. Standing next to Basim is drummer Imran, with an outfit in the style of The Gap. Imran’s casualness – his smile and relaxed attitude of not looking into the camera – marks him of having a «natural» look. Standing on the right side is Shahjehan. Shahjehan’s deadpan face and kurta make him stand out among his peers, especially with The Gap logo superimposed over his ethnic garb. Performing a slightly nervous and uncomfortable subjectivity, Shahjehan’s staged presence is a symbol of the immigrant’s excess foreignness felt by mainstream, white-centric gaze.

This minority-centered intervention of consumerist multiculturalism, I argue, resonates what Prashad terms as «polyculturalism» in his influential text Everyone Was Kung Fu Fighting (2001). In a cultural Marxist approach, Prashad offers a «polycultural» perspective that allows for the «interchange of cultural forms» instead of the multiculturalist view of «the world as already constituted by different (and discrete) cultures that we can place into categories» (2001, 67). A polyculturalist worldview focuses on culture as a process, rather than categories. Ultimately, polyculturalists aim at the goal to dismantle notions of cultural chauvinism, parochialism, and ethno-nationalism. During a phone conversation, I asked Basim what he would like the readers of SPINearth, a music blog offshoot from the SPIN magazine, to know about his band. He said to me, very succinctly, we’re all about (forming) solidarity with all people of color, reaching out to those in the wilderness of North America» (Usmani 2009b). Embracing the collective abject of those around the band, I suggest, The Kominas forges a D.I.Y. polyculturalist unity for a palliative end.

In the next two parts of the series, I identify two strands of The Kominas’ polyculturalist production, both located in musical performances. Part 3 will focus on a performance featuring The Kominas’ forging of solidarity with other Muslim American cultural renegades.

This Song Scares Republicans

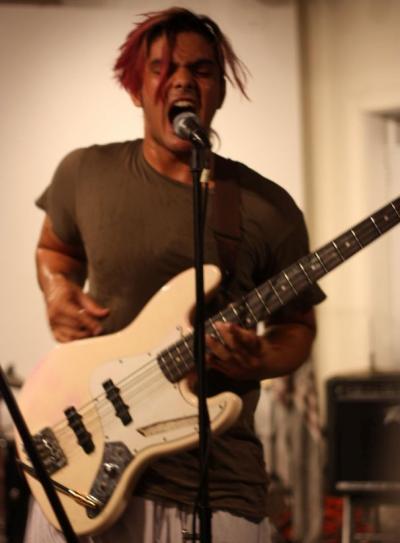

At the St. Stephen and the Incarnation Episcopal Church in D.C., a concert offshoot from the annual meeting of the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) took place. It coincided with the screening of New Muslim Cool (Taylor 2009), a documentary film that follows the life of Puerto Rican American rapper Jason Hamza Pérez who became a devout Muslim activist after abandoning his former life as a drug dealer. Wearing an almost-foot-long purple Mohawk, Basim hopped in front of the microphone (see photo above). He introduced his band by declaring: «It was interesting that when we saw the Facebook listing for New Muslim Cool, we thought, those kids are New Muslim Cool and those (other) kids are «bad Muslims». Basim chuckled and then said, «I’ll let you guys judge how bad we really are».

Basim’s statement not only drew distance from religiously exemplary story of Pérez; it also forewarned the audience, a multiethnic Muslim-majority group of youth [Figure 2], of The Kominas’ «blasphemous» music. A few songs later, Shahjehan announced, «This song really scares the Republicans. This is called «Sharia Law in the USA». The crowd cheers. Shahjehan stomped on his distortion effect pedal, letting his guitar ring with feedback. He threw his back and into the blissful feedback noise. He shaped the noise artfully and projected it with strength at the moment in which chaos and peace converged. Wearing a white kufi, a cap usually worn by Muslim people of African descent, especially in West Africa, drummer Imran raised his arm while holding a drumstick, like a flag. Shahjehan’s guitar feedback bled into a larger bomb like noise created by the rest of the band. Some members of the audience dropped their jaws or covered their mouths. They seemed shocked by the song’s daring lyrics. The others in the audience cheered on and slam-danced across the front of the stage.

As the night deepened, the Atlanta-based slam poet Amir Sulaiman took center stage. A heavyset man wearing a black kufi cap, Amir told his life stories of faith and struggles as a black Muslim living in the U.S. through his impassioned words. Waving his arm, he invoked the words, «I’m not dangerous. I am danger. I'm not fearful. I am fear». He showered the audience with his beads of sweat and heartfelt words, impelled by immense courage and conviction. The crowd drew closer to the stage where the poet stood. The energy peaked at the end of the set when all the performers of the evening joined the poet. Members of the M-Team, a hip-hop duo comprised of two Muslim Latinos (Hamza Pérez’s group) rapped and exchanged verses with Amir Sulaiman. Members of The Kominas resumed their positions behind their instruments forming an army ensemble backing the poet and the hip-hop rhymers.

A Crowd in Tears

A cross-genre jam, the song grew into a trance over the course of nine minutes. It felt like an eternity. Amir Sulaiman chanted the words, «AlHAMdulillah. HAMdulillah. HalleluJAH, yeah, HalleluJAH, yeah, Hallelujah», over strong and steady bass notes ascending and descending - all moving through synchronized cycles of ecstasy. The audience cliques broke up and merged into one. Occupying the left side of the hall, the hip-hop-geared and kufi-capped men, threw their arms up in the air in bursts while swaying back and forth to Basim’s undulating bassline. Loudly, they responded in a chant to Sulaiman’s calling of «Alhamdulilah…Hallelujah....» Congregating the right side of the room were women, some hijab-covered. They added energy into the mix by cheering and chanting «Almaduliah… Hallelujah...» Absorbed by the rapturous moment, the punk slam-dancers transformed their previously ska-skanking bodies into the slow-moving side-to-side wave. Sulaiman elated the crowd further while saying, «I love you. I love you. I love you». This astounding collective power sustained the visceral and the emotional synergy in the room. This blissful and ineffable experience left many of us on and off stage in tears.

In his powerful recitation, Amir Sulaiman syncopated his accenting to the phrase «AlHAMdulillah. HAMdulillah. HalleluJAH, yeah, HalleluJAH, yeah, Hallelujah». The rhythmic repetition of these phrases created a call and response between the poet and his audience structure. The audience recognized the intentional gap in the cycle of repetitions as their cue to respond to the chant. A term mostly used by Muslims, «Alhamdulillah” is an Arabic phrase meaning «praise to God». The meaning of «Alhamdulillah» is similar to that of «Hallelujah», the Latin transliteration of the Hebrew term for «praise Yahweh», used in the Christian context. Juxtaposing two phrases from two different religious contexts - Islam and Christianity, Sulaiman conjured a symbolic inter-faith unity onstage while sonically filling up the space inside a Latino church, in front of a multiethnic audience of myriad relationships to Islam.

Divided into Social Clusters

The Kominas did not compose their parts in the song. The band played the same progression as a looped instrumental track of piano, bass, and drum machine that I found in a Youtube video of Sulaiman’s performance of the song. At the off-ISNA show, The Kominas «rockified» their arrangement, infusing it with an improvisatory spontaneity. Throughout the course of the song, the band built performance energy in the room. Basim played a loop of syncopated bass notes ascending and descending around the fifth, sixth, seventh degree, and the tonic, while supporting the cycle of tension and resolution. Shahjehan played notes in a high register accenting the tonal ebbs and flows. Imran heightened the vigor by playing a drum fill at the end of each cycle. At the end of the chorus chant, Shahjehan signaled the start of the introspective section by a quickly skating and scraping his guitar strings, making a noisy glissando. The band quieted down and receded into the background during the rapid streams of recited words. The instrumental ensemble echoed the emotional intensity of the poem during each chorus chant. The torrent of spontaneous energy and the musical affinity between the performers and the audience, and amongst the performers themselves, resemble the charismatic gospel preaching style in African American churches (Hinson 1999).

Not everyone in the audience who zealously echoed the words of «Alhamdulillah…Hallelujah...» was Muslim-identified. The crowd was divided into a few social clusters. A large group hip-hop-geared African American and Latino men took up about half of the audience. A small group of headscarf-cover women of Arabic heritage stood tightly next to one another near the front of the stage. A mixed-gender, multiethnic group that appeared to be of predominately South Asian descent hovered in the front, standing close to the friends of the band. A few members of this mixed group had shirts that said «Pork Sucks». A group of African American women, some covered in hijab, scattered loosely across the back rows in the audience area. I, as the only individual of East Asian descent in the room, self-consciously tugged myself and my recording devices into The Kominas’ friend circle, swinging my arms and slam-dancing throughout the evening.

These groups all represented the social fringes of the ISNA, an organization that, according to Michael Muhammad Knight, represents «the mainstream, very hygienic and very sterile form of Islam» in the U.S. (Majeed 2009). Basim told me, at the South Street Diner, that the organization has a predominately Arab membership, with the majority of the members being Shia Mulims. The organization has shown political interests in Palestine and the Middle East, and very little interest in South Asian concerns such as the 1947 Partition of India (Khan, et al. 2009). Individuals of South Asian, African American, and Latino heritage and other Islamic sectarian affiliations such as Sunni, as well as those of alternative identifications such as the Sufi Muslims, agnostics, atheists, rappers, and punks are minorities in the ISNA community. The event’s off-site location at a Latino Church, away from the main ISNA convention site of the Washington D.C. Convention Center also signifies the alternative social status and interest of the show’s participants. At this show, the spatial, social rifts among these differently marginalized groups vanished by the end of the evening. The slam dancers were bouncing back and forth like the hip-hop crew. In a chorus, and in unison, everyone threw up their arms and shouted back the inter-faith message «Alhamdulillah…Hallelujah…», regardless of their faith. Everyone swayed. This event was not about division. It was about union, a union among all the social outcasts within and around the American Muslim communities and within the larger U.S. society.

Para-Islamic Alliance

In his novel Osama Van Halen, Michael Muhammad Knight highlights the experiences marginalized by the Arab Muslim orthodoxy. Knight narrative includes the Sufis, the converts among lower-caste Hindus, Turkish nomads, and Subharan Africans, and other fringe, unorthodox Islamic practices in Black America that was swept under the rug by Arab Muslim cultural elites:

«It also happened in the wilderness of North America, where Islam took new forms - irrefutably black, with its own black scriptures, black symbols and black holy men... This black Islam even spawned strange culture seeds; from the Moorish Science Temple came the Moorish Orthodox Church, with opium-waltzing Walid al-Taha and his student Hakim Bey using the black man’s code to fit their facts, as Norman Mailer said of the Kerouacs and Ginsbergs. Many these days would also view the Progressive Islam scene as a homegrown heresy, and American Muslim women have fired the first shots to create a whole other Islam for themselves. And now even the bums and punks are starting to stand up on the margins - kids like the Kominas’ Basim and dead zombie Shahjehan - to claim their corner» (2009: 68-9).

Similarly, The Kominas looks to these sites of social transgressions to create an alternative cultural space around orthodox Islam. Behind the mission of building networks among individuals in the fringes, regardless of their idiosyncratic relationship to the contemporary Islamic orthodoxy, the band align themselves with an anti-status-quo heterodoxy. The Kominas shatters the stereotype that music is forbidden according to some extreme interpretations of the Islamic law upheld by Western, non-Muslim groups (Blumenfield 2007: 210-1). The Kominas and other Taqwacore-affiliated groups challenge this shallow assumption. Basim said in the CNN interview, «We aren't [just] some alternative to a stereotypical Muslim. We actually might be offering some sort of insights for people at large about religion, about the world» (Ansari 2009). In an interview with The Kominas, Hussein Rashid, scholar of Islam and American religious life, employs the term «Islamicate» to refer to «things that may be influenced by Islam, but are not necessarily religious» to describe the band’s music (Rashid, et al. 2009).

Building on Rashid’s distinction, I refer to The Kominas’s worldview as a «para-Islamic» perspective. The prefix «para» refers to the position of being alongside, or closely related to. I argue that The Kominas’ music critically engages with the cultural, social, and political milieux around and alongside Islam. The Kominas’ music does touch on topics related to Islam, specifically how it’s experienced, perceived, translated, exoticized, and excluded. But it does not not disembody perceivable religiosity within the Islamic faith, as the press has (mis)construed. This approach, I argue, occupies a middle space between religiosity and agnosticism. This space of ambiguity generates discomfort and anxiety for many, conservatives, liberals, the Christian fundamentalists in the US.

The Kominas insist upon a holistic, polyculturalist view of Islamic cultures: They push the edges of public consciousness, reminding everyone that Islam is not just one religion, generalized, flattened, antithetical to «Western» values and culture. They daringly reveal the fringes of how these living cultures associated with Islam intersect with issues of race, ethnicity, nationality, globalization, war, politics, media, pop culture, sexuality, humanism, humor, alienation, love, and other facets of culture and humanity. Retaining a multitude of differences within and around the cultures of Islam, The Kominas’s musical dissent challenges the world to wrestle with the profundity of religion and the inequities of life. And this is how the band reach out to those alienated in the wilderness.

Minoritarian Vision

The multiplicity of The Kominas has created amorphous and powerful social resonances for their fans and friends. With an intentional cultural ambiguity, the band enacts a minoritarian vision of social inclusion. The Kominas evoke a brown-and-punk continuum akin to the taqwacore subaltern spirit. Through mobilizing this discourse, the band unifies a conglomerate of fringe social groups.

This conglomerate points at a polyculturalist (Prashad 2001) solidarity with those who fall outside of the white norms (and the US American black-white racial binary) in rock music-culture and by extension, in the U.S. and global society: Indians, Pakistanis, Latinos/Chicano punks, Afro-punks, Native Americans, Sri-Lankans, Southeast Asians, West Indians, Sufis, Arabs, Taqwacores, Muslims, immigrants, migrant workers, socialists, queers, the disabled, and other «others». Invoking an inclusivist punk brownness, The Kominas makes clear its home-base in the South Asian and punk worlds. Declaring its status as a minority within a minority group, the band branches out to touch those who are similarly marginalized within the society.

The Kominas frequently associate with other non-South-Asian musical groups of color. Forging an alliance with other artists of color took different forms. The band has shared a stage with a number of musicians and groups associated with Afro-punk: Amul 9 from Atlanta, GA and Sean Padilla, also known as the Cocker Spaniels from Austin, TX. Basim devoted a session of his online radio podcast series Basim’s Goth Hour to the music of Afro-punk. Additionally, the band made a short video satirizing American xenophobia and racism against «ethnic Americans» such as themselves and Mexican immigrants. Using jingoist imagery such as American fast food and mall culture, and conservative media rhetoric including «American responsibility», «collateral damage», and «support for the Taliban», the video marks «Ethno-Americans» - specifically, The Kominas, Das Racist, and Mexican immigrant workers in the food service industry - racially distinct from the right-wingers’ ideal «America».

«Brown Brothers»

Notably, the band has forged a connection to Latino punk. In the liner notes of their album Wild Nights in Guantanamo Bay, written on the bottom of the page in fine print, I found a sentence written entirely in Spanish: «para todos mis carnales cafes del mundo que chinga su madre el gobierno americano y que viva la raza». This message suggests an anti-U.S.-government stance: «For all my brown brothers in the world. Fuck you, American government and long live, the people». From my bilingual Chicano friend, I learned that the phrase «carnales cafes» («brown brothers») does not exist in formal Spanish. The statement «viva la raza», meaning «long live the people», is a phrase or protest slogan used by Mexican Americans to evoke ethnic solidarity with one another during the Chicano Movement (Alaniz and Cornish 2008). The Kominas employed a literal translation of the term «brown brothers» to show their alliance with Mexican and other Latinx immigrants over a shared brown identity.

It wasn’t until I went to The Kominas’ first show that I got a better sense of what this cross-ethnic alliance may mean. In a musty basement, I was caught in the middle of a swirling crowd of sweaty bodies. This was Nick’s Basement, two blocks away from the University of Massachusetts Lowell campus. Los Bungalitos, a local punk band, blasted its distorted power chords out of a decrepit Marshall amp. Shouting words in English and Spanish, the hardcore vocalist hyped the crowd, combusting the basement with energy and making the walls shake. In a conversation over the loud hardcore band, Shahjehan screamed into my ear, «The singer of Los Bungalitos is incredible. I love this band!» During the Los Bungalitos’ set, The Kominas set up their equipment. Shahjehan stood facing a short stack of guitar amplifier speaker cabinet while tuning his guitar. He wore a black kurta with gold embroidery. There was a sea punk signifiers in the basement like guitar mohawks, dim lights, skinny jeans, hoody sweatshirts with patches, guitar feedback, beers, grunts, chants, sweat, handmade merchandise and zines, fists of camaraderie, etc. A surge of social energy brought together a constellation of punk, brownness, and immigrant identities.

Immigrant Rights and Anti-Assimilationist Politics

In «Blow Shit Up», a bilingual song with Spanish verses, Basim repeated the lines, «I don't want assimilation / I just want to blow shit up», over and over again. Jumping, shouting and body-surfing, the band pranced around the stage area and then lunged into the audience. On a burst of adrenaline, the band celebrated their co-presence with friends and compatriots. The Spanish verse of this song is an excerpt from «A Las Barricadas», a well-known tune of the Spanish Anarchists during the Spanish Civil War. With a punk association, this anti-establishment fight song has been covered by many artists including Brazilian hardcore band Juventude Maldita and Estonian punk band Vennaskond.

Songwriter and Guitarist Arjun borrowed only the first stanza of the original version: «Negras tormentas agitan los aires, nubes obscuras los impieden ver, aounke los espere el delore la muerte contro el enimigo los yama el deber». The verse translates into English as, «The black storms agitate the airs / The dark clouds impede our view / Even death and pain wait for us / Duty calls against our enemy». This passage paints a dark imagery of war and a sense of urgency for a battle. The Spanish verse allows Spanish-speaking Latinx individuals a unique cultural vantage point. This is an instance of social bridging between the brown-identified South Asians and Latinos and Latinas in the United States. Conservative rhetoric against immigrants have manifested as censures against speaking Spanish in schools and in other public spaces. Within this political climate, the Spanish citation within the song is read as an anti-assimilation gesture.

Brownness as an Immigrant Identity

I argue that this bilingual anti-assimilationist articulates the position of two subaltern groups in the current United States political landscape: the Spanish-speaking Latino/a immigrants and the individuals of Muslim, South Asian, and Arab descent who run the risk of being stereotyped as bomb-throwing terrorists. Uniting the two enemy groups of the state could be a response to the so-called «the Al-Qaedization of Latino identity»: a political process that fosters a conservative and near white-supremacist homeland security culture, lumping the «bad» Latinos with «terrorist threat» (Lovato 2006). This race-based attack has targeted Chicano activists. Slandering Chicano activists as «America’s Palestinians» [who] are gearing up a movement to carve out the southwestern United States… meeting continuously with extremists from the Islamic world» (Mariscal 2005: 43; cited in Maira 2009: 244).

With the vision to dismantle the racist backlash against Muslim and Latinx immigrants, The Kominas stake a claim to their brownness and highlight a similarity between the Muslim and Latinx Americans living in the United States. The articulation of ethnic brownness is rooted in anti-assimilation politics. In «Blow Shit Up», The Kominas align themselves with the left-leaning spectrum of the Latino/a immigrant community. They embody an inter-ethnic brown identity driven by immigrant politics. Maira describes this kind of political affiliation as being based in a «shared political relationship to the nation-state rather than a shared identity based on culture or color» (2009, 180). I would argue for a slight different theoretical relationship between the two. Rather, for The Kominas, it is upon this shared political relationship to the nation-state that their inter-ethnic identity has been built. The Kominas’ cultural activism is not only driven by their own dissent as postcolonial brown subalterns (Hsu 2013), but also equally fueled by the shared narratives of being unjustly treated as non-citizens in the United States.

Playing loud and high-energy music at the basement show, The Kominas led a multiethnic crowd to throw up their fists shouting «oi-oi-oi»!The band intentionally decontextualized the punk anthemic «Oi»! shout from its historical association with the working class and white-supremacist punk skinheads in the United Kingdom. For the here and now inside Nick’s Basement in Lowell, and around in The Kominas’s social sphere, the band’s «Oi!» chant spread an anti-racist and anti-U.S.-assimilation resonance. Embracing the abject in the style of punk, The Kominas’s «Oi!» shout-outs reached fellow youth of color, some of whom were brown Latino/a, others were brown Asians.

Epilogue

The Kominas embody the punk anti-establishment ethos to challenge the essentialist notions affiliated with South Asian and Muslim identities after September 11th. The band brings together various contestational micro-universes among subaltern groups via a polyculturalist, brown, pro-immigrant identification. To conclude this series, I should recapitulate the meaning of Taqwacore and emphasize that Taqwacore was a cultural phenomenon that was born in a specific historical moment. Some of what falls under the umbrella of Taqwacore has dissipated and transformed into other progressive formations questioning the political and cultural status quo. It’s worthwhile to mention that the Taqwacore spirit still lives on. What has gone under the Taqwacore banner is an interpretation of Islam and the humanities surrounding it. It is also an interpretation of life in the era bombarded by intensive global exchanges of media, music, ideologies, images, subcultures, dissent, affects, and spiritualties. The life of Taqwacore resists discursive simplifications and social injustice. What I know is: Taqwacore is a not a religion. It is not even an alternative to «Islam», as portrayed by mainstream U.S. media. Taqwacore is a cultural space for alternative understanding, practices, identities, and relationships to and around Islam. And the journey to understand it only begins, and should not end, with The Kominas’ music.

List of References

Biography

Published on April 10, 2017

Last updated on April 10, 2024

Topics

About the ups and downs of cross-cultural creativity: Korean reggae, vaporwave, and the worldwide Hindu Holi festival.

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

From Muslim taqwacore to how the rave scene in Athens counters the financial crisis.

From priests claiming to be able to shapeshift into an animal to Irish folk musicians attempting to unify Protestants and Catholics.