Looking at the history of early New York disco, ethnomusicology scholar Bruno Rana focuses on the role played by the Italian-American community in the U.S. in the development of the scene from a cultural, anthropological, and technical perspective. In a territory where migration is a hot topic these days, reflecting on the Italian diaspora’s cultural impact could foster a less toxic debate on the presence of ethnic minorities in the peninsula.

The history of disco as we know it today could not be written without taking into account the contribution of a substantial number of Italian-American DJs, especially from the early days of New York City’s club scene: Michael Cappello, Steve D'Acquisto, Francis Grasso, David Mancuso, Bobby Guttadaro, Nicky Siano, … and the list goes on.

Saturday Night Fever

Why was this contribution so sizable? Moreover, can this account be employed in a wider perspective to highlight the positive impact of a musical conversation between displaced communities and their host countries? This article will attempt to answer such questions by examining the role of the most prominent Italian-American DJs operating in New York City in the early 1970s, as well as the innovations and intuitions they brought to the table.

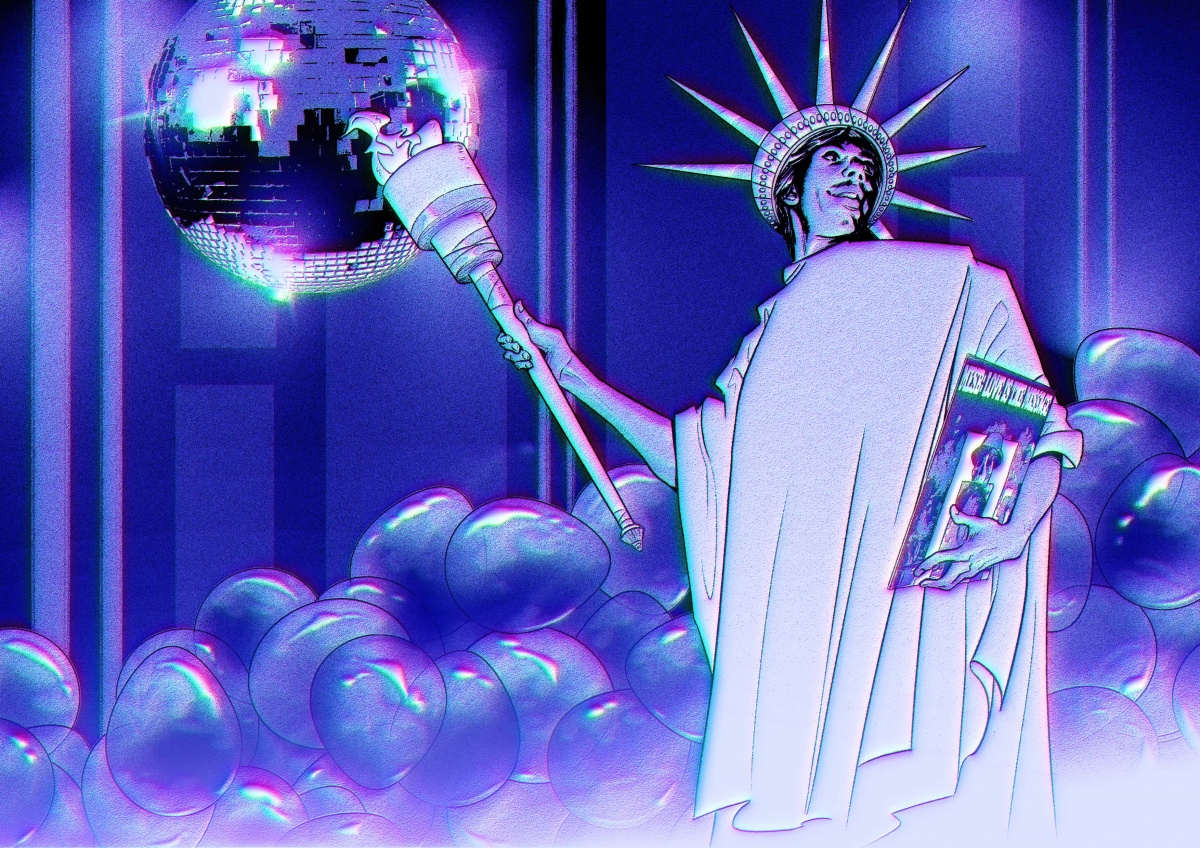

In an effort to find a logic to this Italian-American pattern, Tim Lawrence in his book Love Saves the Day (2003) argues that spinning records was a «hip, new profession of low to middling status that suited Cappello and company’s second-generation aspirations. As the children of immigrant parents», he continues, «they were already familiar with insecurity and upheaval, and they used this know-how in order to negotiate the unstable terrain of the nightworld». They symbolically recreated their ancestors’ migratory cycle by carrying their precious bags of records from one venue to another.

According to Nicky Siano (2018), another element that ensured jobs for Italian-Americans was the structural infiltration of the Mafia in NYC’s nightlife fabric: «What is the Mafia infamous for? Hiring their own! You’re Italian? Oh, You’ve got the job!»

Certain People Will not Mix or Blend

Waves of Italian migration to America can be traced back to the 19th century. Tellingly, accounts of a sizeable number of migrants mainly from Sicily entering the musical realm of New Orleans speak about the American perception of Italians as non-white people (Zenni 2016). Italian practitioners felt kinship with Black, Jewish, and Latino musicians and would contribute significantly to the evolution of jazz music.

In 1924, during a ceremony to present the Johnson-Reed Act through which America attempted to tackle mass-immigrations, the president of the United States Calvin Coolidge stated: «Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend» (PBS 2015).

Curiously enough, some fifty years later a group of young men of Italian descent taught America how to mix and blend two music tracks together in a functional yet creative fashion, paving the way for what would be globally regarded as the art of DJing. One of the first spinners who pushed the practice forward was Francis Grasso. Back in 1970, the long-haired youngster would «hold the disc with his thumb while the turntable whirled beneath insulated by a felt pad, […] locate with an earphone the best spot to make the splice, then release the next side precisely on the beat» (Goldman 1978). Grasso would also experiment with sounds by simultaneously playing two tracks for several minutes. These tricks would be performed live at the discotheque, absorbing the vibes off the dance floor and sending them back to the dancers via the gigantic loudspeakers of the club. Soon, Grasso would share these technical novelties with his DJ peers Steve D’Acquisto and Michael Cappello, setting a new standard for the DJs to come.

Egalitarian Utopias

In parallel to these DJs, albeit outside the grand scheme of ordinary discotheques, the emblematic David Mancuso made a name for himself as well. As an ideal link between the summer of love’s spirit and the burgeoning club culture, Mancuso focused on creating an environment of «egalitarian utopia» (Petridis 2016) in which the cohesion between the DJ and the raving crowd would be the distinctive trait of his invitation-only parties. Music (and LSD) would glue the two elements together. The designated place to achieve this unity of people of all classes, color, sex, and sexuality was a loft space on Broadway in Manhattan. Taking inspiration from both the intimacy of the rent party scene and his memories of children’s parties at the orphanage where he lived at a young age, Mancuso would fill the place, which also functioned as his house, with balloons and prepare fruit punch and organic snacks for his weekend guests. Launching his format on 1970’s Valentine’s Day and famously naming the inaugural party Love Saves the Day, Mancuso quickly established himself and his Loft as the focal point of Manhattan’s underground dance scene.

The success of these game-changing private parties inspired another young mixer and Loft regular of Italian origin to become involved in the rising scene. Nicky Siano, a confident and flamboyant teenager at the time, would soon gain the adequate DJ expertise and push the practice a few steps forward. After sourcing turntables with variable speed, he improved Grasso’s technique by experimenting with the records’ speed, matching the tempo of one another. He would also bring a third turntable to the booth in order to add sound effects during his creative blends. As Freddie Knuckles would later say «It became difficult listening to other guys play in the old style after that» (Lawrence 2003).

Not only did he become the hottest spinner in town due to his distinct performative style and charismatic personality, he also became a friendly competitor to Mancuso’s parties by opening The Gallery a few blocks down from the Loft’s address. Siano was peculiarly interested in achieving the best-sounding and best-looking venue. He put great effort into enhancing his sound system to make it sound crisp and balanced no matter where in the room the attendees were dancing, and working on his lights to obtain the best scenic and evocative results feasible at that time. The aforementioned Knuckles and his friend Larry Levan were two Gallery’s aficionados and soon they would move their first steps behind the wheels of steel under Siano’s wing and become the first wave of African American disco spinners in New York City.

This Is Only a Warm-Up Set

The impact and long-lasting legacy of these Italian-American practitioners is almost incommensurable. Despite this, for many years the prevailing music narrative was imbued with a rather limited and demeaning vision of the disco scene and genre. With little to no interest in disco culture, the Italian heritage of the original disco pioneers was therefore not spotlighted enough.

In recent years, the blossoming of gender studies and postcolonial studies has fostered the revaluation of the early days of disco in light of its contribution to LGBT and ethnic minorities’ causes. Disco has retrospectively become an important and fertile subject to be analyzed, allowing the Italian case to finally be treated adequately.

Taking these themes one step further, I would argue that key studies such as the one presented in this article can indeed demonstrate how mutually beneficial a musical dialogue between diasporic communities and their host countries can be. Particularly in the Italian peninsula, where migration is a hot topic these very days, such interaction can be seen as an opportunity to explore and nurture diasporic music practices as they may contribute to the Italian sound of tomorrow.