Silence Is the Real Taboo

In Beirut every gunshot has a different meaning. There are sounds of war and of celebration. The lebanese musician Serge Yared explains how they are used in music. From the Norient book Seismographic Sounds (see and order here).

Hello, I am Serge Yared, singer/songwriter, importer of Italian heating systems, music consultant and occasional DJ. I am thirty-six years old and, like any person in his mid-thirties who has lived in Lebanon most of his life, I am familiar with war sounds. I have indeed witnessed an Israeli invasion (1982), Israeli and Syrian occupations (South-Lebanon by Israel between 1982 and 2000 and when Syria turned Lebanon into its quasi-protectorate between 1976 and 2005), an endless series of car bombings (during the civil war and after 2005) and other targeted killings and civil unrest (the 2008 civil war simulation).

In Beirut there is a twinning of the sounds of war and sounds of celebration. When you hear a gunshot you wonder: «Is Hassan Nasrallah giving a speech?»; «Did they already release the Baccalaureate results?»; «Are we burying someone today?»; «Are you sure these are not fireworks?» Our Lebanese ear is trained to localize these sounds and then to interpret them. A gunshot from Sassine Square (the symbolic heart of Beirut’s Christian community) has a different meaning than a gunshot from the Southern suburbs like Dahiyeh (a predominant Shia Muslim neighborhood).

It has become so much a part of our socio-cultural fabric, that several Facebook pages were created to publically denounce celebration gunshots and the abusive use of fireworks. In a perverse twist, many find these sounds reassuring because they connote home. Switching into war mode might be easy for the Lebanese, as our geopolitical position has been one of decades-long contingency. We sit on a figurative volcano, waiting for the next eruption. The poor infrastructure left over by the civil war twenty-five years ago institutionalized a state of vigilance. We can now rely on generators when the electricity gets cut and private water distribution companies thrive during the summer. Paradoxically, Lebanon creates stability from chaos.

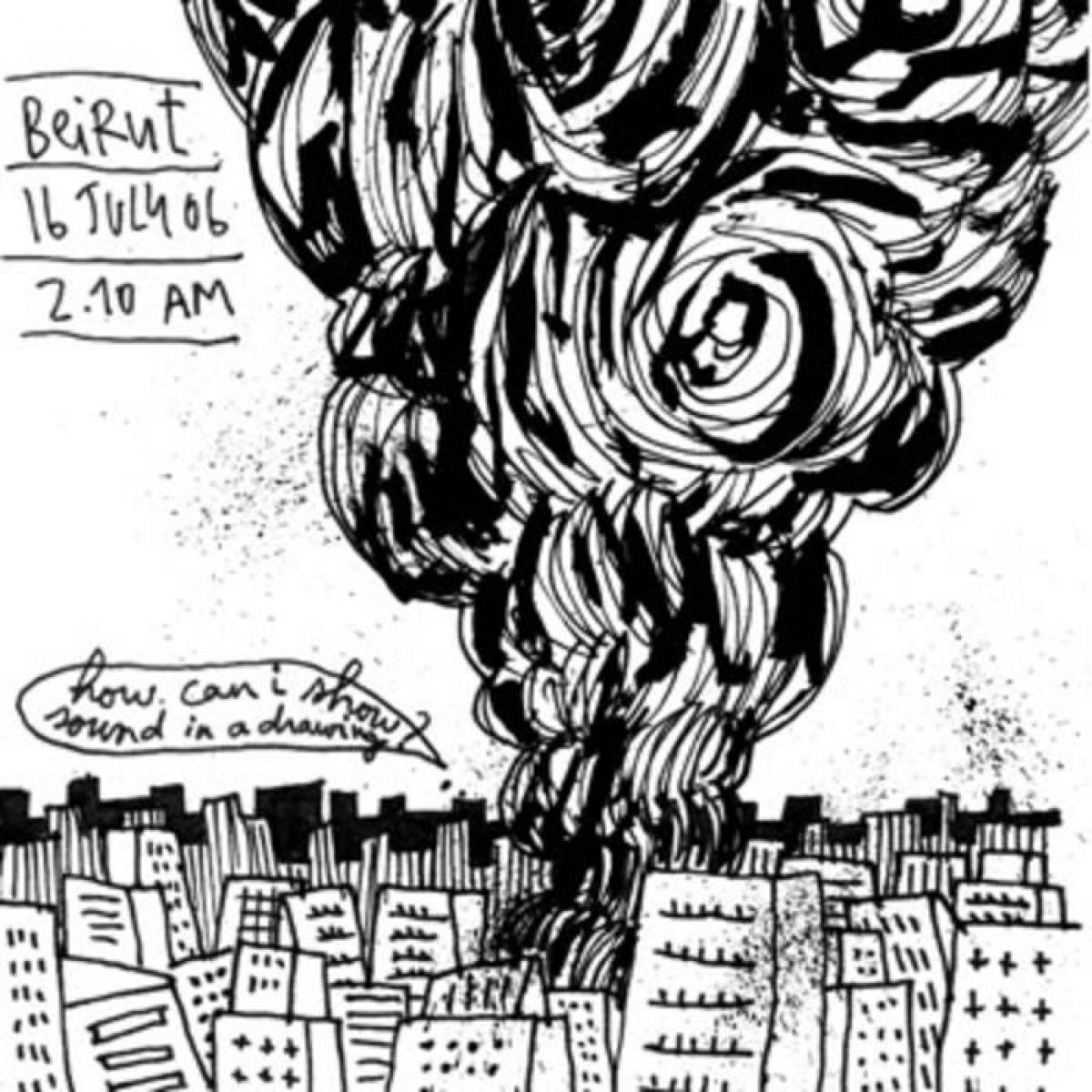

In this precarious context, war sounds and their use in music are not taboo. Any Lebanese citizen is a potential emitter of war/celebration sounds, thus aestheticizing it is just a few steps removed from experience. This has been epitomized by experimental trumpet player Mazen Kerbaj and his figurative duet with Mark 82 five hundred pound bombs («Starry Night»), the ones dropped by the Israeli army during the 2006 War with Hizbullah. Another example is the 2006 War Trilogy by electronic artist Munma.

Silence is the one real taboo in Lebanon. Sounds of war are not half as distressing as the silence that comes before and after them. One has to understand that if there is one city embodying the concept of saturation it is Beirut: it is saturated with different ways of life, dialects and languages, smells, cars, buildings of varying shapes, sanguine body language, and hedonism. This saturation is channeled through the media and many art forms. I have recently deactivated my Facebook account because of the noise generated by debates and constant requests. It felt like closing a double-glazed window overlooking a boisterous street.

My art as a musician and as a member of the band The Incompetents channels this saturation, too, with all of the illogical influences, emotions, characters and genres. My friend and conceptual artist Alfred Tarazi does something similar with his collages. He dreads blank spaces. As our exclusive cover art director and designer he managed to combine seven different fonts for our I’m Really Important Back Home EP cover (2011). If «less is more», in Beirut «more is never enough».

The ethical mission of the musician is to bring critical depth, to help scrutinize our past. Paraphrasing Lacan, «to have a past and not be a past» is our goal. In this respect we have mostly failed as a scene and this failure is fascinating. You would expect new ideas and real dissent from a deliquescent society that doubts itself – think of Viennese symbolism that aesthetizes decadence, of the Weimar Republic’s Berlin, of punk in England circa 1977, or of the degenerating and liberating Movida in post-Franco Spain. Beirut should belong on this list. Perhaps a vow of silence is what we need to do collectively, a therapeutic form of resistance.

This text was published first in the second Norient book Seismographic Sounds.

Biography

Shop

Published on October 30, 2018

Last updated on May 06, 2024

Topics

How do acoustic environments affect human life? In which way can a city entail sounds of repression?

How does Syrian death metal sound in the midst of the civil war? Where is the border between political aesthetization and inappropriate exploitation of death?

Special

Snap