Reflections on the new multi-local musical Avant-Gardes of the 21st century. An essay on the Lebanese musician Tarek Atoui, Luigi Russolo, Mazen Kerbaj and many artists more.

To me, Tarek Atoui represents the new, truly transnational musical avant-garde of the 21st century. Atoui was born in Lebanon in 1980, and like his contemporaries, he experienced the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) and was socialized by the sounds of war, soon learning to recognize weapons by their sounds alone. However, in 1998, his life as a cosmopolitan commenced. He had moved to Paris where he studied music at the French National Conservatoire of Reims and collaborated with IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique) at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The French-funded IRCAM was founded by Pierre Boulez and hosted such famous teachers as Xenakis, Globokar and Nono. It was one of the biggest and wealthiest institutions of the avant-garde of the twentieth century (similar to studios of new music and electronic music in Germany and in different cities of the West).

One artist, often called a pioneer of this old musical avant-garde, was the Italian painter and Futurist Luigi Russolo. His famous manifesto from 1913, «The Art of Noises» glorified explosions, rifle fire and the dissonance of industrial machinery. To Russolo and such similar writers as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Paul Jünger and Paul Virilio, war resembled a fascinating aesthetic and mythical phenomenon, showing human kind in its whole beauty – both passion and reality (Witt-Stahl, 1999). Russolo and his fellow Italian Futurists encouraged innovation and wanted to outdo the German-Austrian classical music superculture (Ross, 2007). They no longer were moved by the increasingly complex and dissonant patterns of the great composers’ orchestra music, therefore they sought to include other noises and to create new instruments. To them, music was supposed to resemble the realities of modern life. Fascinated by war and its weaponry, many of the Futurists sided with Mussolini’s fascist regime. For some observers, the Futurists were simply a reactionary fascist group; however, for others, they seeded the ideas for many innovations to come.

From Rural to Urban Sounds of the Middle East

Tarek Atoui is well familiarized with Luigi Russolo and the other heroes of the musical avant-garde from Europe and was more than happy to share his MP3 and WAV files with me. In a hotel lobby in Amman we wired our laptops together, and I copied them all – tracks from Karlheinz Stockhausen, from Musique Concrète pioneers like Pierre Schaefer, Luc Ferrari, and Iannis Xenakis, who was of Greek decent. Xenakis, like many others throughout time and in different fields was fascinated by the sounds, melodies, rhythms and noises of the Orient.

On a side note, please listen to the Javanese Gamelan of Debussy, and to the later Orient hallucinations of the US-American jazz and pop avant-garde: the Beat Generation in the 1950s and the psychedelic rock and hippie movement in the 1960s. Psychedelic rock was hip in the Arab World as well. In Beirut alone nearly 200 bands performed psychedelic rock concerts and laid the foundation for the subcultural music scene in Lebanon. Listen to such composers as Bartok and Kodaly from Eastern Europe and Russia as well. For them, non-Western was often rural; however, to Tarek Atoui non-Western is urban. This is one of the many reasons why he belongs to the new, truly transformational avant-garde.

Nonetheless, Bartok and Kodaly influenced an entire generation of musicians and composers in Lebanon, the Rahbani Brothers and Fairuz, Zaki Nassif, Tawfik Sukkar, Tawfik al-Basha and others. From the 1950s onwards, supported by the radio stations Radio Lebanon and al-Sharq al-Adna and by the Christian political establishment, they created what is often referred to as Lebanese music. This style of music took elements from village music, removed some of the harsh sounding instruments, introduced European harmonies and made it accessible to the Beiruti bourgeoisie (Manguy, 1969; Weinrich, 2006; Stone, 2008; Asmar, 2001, 2004, 2005).

In 2005, Atoui returned to Beirut for the first time for a period of one week, during which time I met him in a fashionable bar in Hamra. Atoui had heard that musically, Beirut was on the move. Mazen Kerbaj, Sharif and Christine Sehnaoui began experimenting with free improvised music in the end of the 1990s and the scene had grown quite steadily, and was now ready. In terms of quality, musical pioneers such as the German saxophonist Peter Brötzmann were no longer that far away. In fact, I found Brötzmann’s album “Machine Gun – Automatic Gun for Fast and Continuous Firing” and a selection of free jazz and free improvisation music from Europe and the United States in the apartment of the trumpet player Mazen Kerbaj in East Beirut.

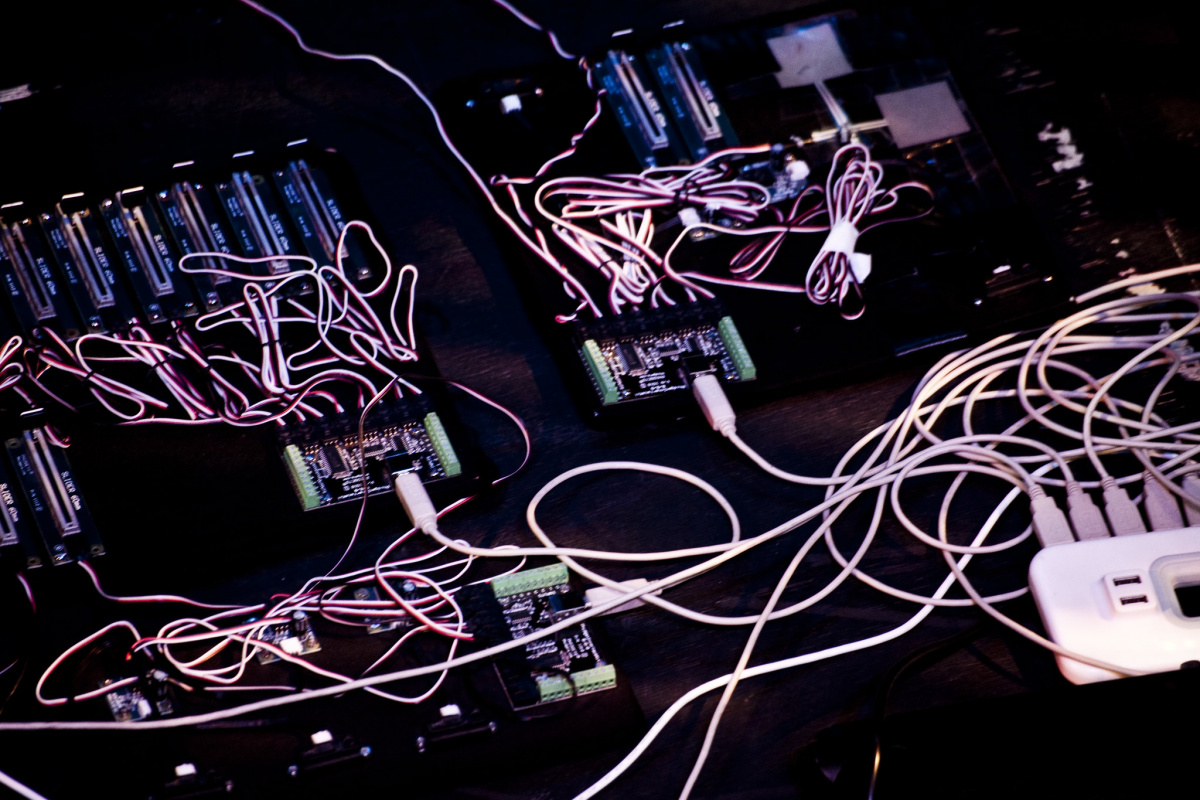

In Beirut, Atoui wanted to discover this scene and the up-and-coming subscenes like post-rock with an experimental touch (Scrambled Eggs), noise to grindcore (Xardas), electro-acoustic works (Cynthia Zaven) and glitch. To do so, Atoui returned to Beirut in 2006 for three months. He organized two workshops and presented MAX/MSP to many of the upcoming musicians in Beirut. It is with this software that Atoui creates his highly complex mixtures of digital soundscapes, abstract beats and noises. He also held children’s workshops in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, during which he taught children to record and film sounds and images from their local surroundings and to edit the video and sounds into collages.

In addition to the workshops, Atoui performed regularly. In his performances, he created soundscapes full of ruptures, cuts and contrasts, and mashups of intense noises, digital frequencies and samples from different sources including field recordings, voices (Arabic, English, Chinese, etc.) media files (from radio and TV), popular music (Arabic strings, Chinese opera, etc.), war sounds and much more. Listeners receive the sounds in different qualities (lo-fi to hi-fi) and compressions (MP3 to Wave), and Atoui adds reverb, distortion and other effects to the mix. The resulting sounds are then sent to the left and right channels and to the foreground and background of the speakers. It is from these performances that we find many reasons to include Atoui within the new avant-garde of the 21st century. His music is not intellectual and stiff, but rather switches within seconds between old categories of high and pop-culture, and while a bit more extreme, it is similar to pop-avant-garde streams in the United States.

Atoui does focus on his performance as much as on the finished piece of music. He spends a lot of his time developing what some call «psychological» interfaces. These interfaces enable interaction in real-time between him as a musician and his laptop. On stage, he ‘plays’ his laptop like a famous rock guitarist plays his guitar. To do so he uses self-built controls to steer his software. At first, Atoui stands still while his music plunges through chaos, with noise and rhythmic structures originating from all possible directions. Then his body starts to move, as he introduces breakbeats. Hardcore drum’n’bass begin structuring the soundscape encapsulating beats from the well-known canon of popular music and club culture. On YouTube one can see Atoui in action – sometimes he performs without a shirt, and the sweat on his body shows the intensity of his music. Russolo and some members of the old European avant-garde would have a fit if they saw these hedonistic performances.

Music resembles the structures of the society in which an artist lives – as several ethnomusicologists argue at times (Blacking, 1976; Erlmann, 2005). Tarek Atoui lives in an increasingly digitized and transnational society where his musical samples derive from here and there and from the past and the present. While his mixes and mashups are full of breaks and ruptures, his life is fairly chaotic as well. It is possible to reach Atoui via Skype, Facebook and email, but never via landline. Since 2005, he has lived without a permanent place of residence. He travels from job to job, performing well-paid events in art universities in Europe, poorly paid gigs in small music venues and giving lectures and organizing workshops in the Middle East funded by an international art and development NGO. Recently, he has spent his time performing and working in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates. He must constantly negotiate between his own artistic visions and the diverse demands of his various hosts as he moves between the worlds of art, theater, dance and music. Switching between contexts of this sort resembles those from the pop avant-garde born in the United States, or rather, as some have called it, experimental music from non-musicians who were educated at universities of art. These non-musicians have more freedom than the musicians who are stuck in the large institutions of the music world (Kahn, 2001, 104).

From Arabic Music to the Noises of War

What upsets Tarek Atoui and his musician colleagues in Beirut the most is when international art organizations, music lovers, and ethnomusicologists from the United States and Europe argue that their music sounds too Westernized. They often feel pressured to introduce more elements from Arabic music, a style they are often unfamiliar with for various reasons. For example, the European style teaching of Arabic music let many musicians flee away from this musical canon (Burkhalter, 2007, 2011; Racy, 2003; Touma, 1998). According to today’s musical avant-garde in Beirut the demand to introduce more Arabic music is simply dim-witted – and some of these artists have learned how to confront what they call the Orientalist demand.

Mazen Kerbaj opened this debate on the interrelation between music and the sounds of the Lebanese Civil War while being interviewed by a German journalist. «Maybe one hears the Lebanese Civil War in our playing, I told the journalist», Kerbaj told me during one of our interviews. «Sharif and Christine Sehnaoui, who sat next to me, almost burst into tears from laughter when they heard me say this.» Was Mazen Kerbaj’s answer simply a strategic move to answer the frequent questions about «authenticity» and «locality» that foreign journalists, international funders and scholars continue to ask? Or was it more? It is certainly an interesting answer to a challenging question: How are sounds heard during one’s childhood and youth translated into one’s later artistic expression? Indeed, the blubbering, jarring and clapping sounds that Kerbaj produces on his trumpet seem to resemble the sounds of rifles and helicopters. Is this more than just the imagination, or simply wishful thinking? If we seriously analyze the issue, it becomes clear. The surroundings in which one grew up have an impact on the music of a musician. However, this impact takes place on the deepest levels of musical creation, not necessarily on the surface. However, superficially, one could read these strategies of working with the sounds of war as a move not to «disappoint» international audiences. One could critically argue that the “exotic” flavor of the sounds of war replaces that of Arabic music. Particularly outside the field of music, many Lebanese artists who present their works internationally use memories, images and audio samples from the Civil War (or from the 2006 war between Israel and Hizbullah), some of which are hidden and others readily apparent. In doing so, they create a certain «locality» or even «authenticity». Atoui is extremely critical of these artistic strategies; however, he knows all too well that this topic is too complex to judge quickly and easily.

Some Beiruti musicians follow different paths to create local sound. Some follow the renewed transnational trend for psychedelic music, and the best of these work with psychedelic music from a perspective different from many of the musicians from Europe and the United States that work in the field. They are aware of what the samples they use represent within the Middle Eastern context, or at least, they understand the lyrics of the sampled song bytes.

Raed Yassin, a colleague of Tarek Atoui, manipulates sounds from Lebanese and Egyptian pop culture on his new label Annihaya. His pieces function on the aesthetical level primarily, as they become hidden audio-narratives that comment critically on social and political issues. In the worst case however, some of the Lebanese musicians do not know much about the psychedelic media samples they utilize, often because they grew up in the city within elite families, and thus pop culture from rural areas is rather foreign to them. I felt this strongly after the 2006 war, when many Lebanese video producers went to South Beirut and to southern Lebanon to film the destruction. Some of these artists were entering these areas for the first time, and in their short videos they often talked and behaved like tourists – thus, the gap between the avant-garde and the non-elite and rural-pop culture still exists today. Most of these Beiruti musicians studied in art schools, and not in the rather conservative National Lebanese Conservatory. Some of them grew up in huge villas as well.

In Jennifer Fox’s documentary film, Beirut – The Last Home Movie, we see Sharif Sehnaoui as a little boy. The film offers insight into the daily life of a well-off Lebanese family living in East Beirut. We see the family members working in the garden and cleaning the house, while we hear shooting and shelling nearby. To forget the harsh realities of war, the women depilate their legs, and the men compete in car races through the narrow streets of the Lebanese mountains. Often times, the family sits together in the shelter with friends from the neighborhood during heavy bombardments. Little Sharif and the other children have the attention of the whole family upon them, as they play games, watch animated cartoons and are allowed to stay up late. Everyone ignores even the loudest explosions. Imprisoned by the war, the family creates its own private world, in which they pretend to live an ordinary everyday life. Despite attempts to convince themselves and their children that everything is okay, in the end this strategy does not work, argues the Lebanese anthropologist Samir Khalaf. The war affected all the Lebanese, with even the rich and educated suffering from trauma. While one should not judge the elite for being better off, their experience should probably not be compared to the experiences of those from the poorer groups. «There is hardly a Lebanese today who was exempt from these atrocities either directly or vicariously as a mediated experience. Violence and terror touched virtually everyone.» (Khalaf 2002, 236) Among these elite musicians, some saw the death of family members or friends with their own eyes.

From our first conversation, Tarek Atoui convinced me with his clear and cogent positions on these complex and delicate topics and questions. He tries hard not to mix his role as a musician with his role as a social actor and a human being. Within his music, he strays close to the European concept of creating art for art’s sake. Art for art itself is political, because it aims to inspire people to move beyond commercialism, propaganda, and in his case Orientalism, a necessity for not only Lebanon, but for the transnational music worlds as a whole. Atoui believes that artists can play a direct role in changing societies as well, thus why he works on social projects and in workshops. However, these are separated clearly from his artistic career.

For me, this again puts him within the ranks of the new avant-garde of the twenty-first century. This new avant-garde evolved outside the Euro-American world and it creates increasingly strong artistic and political positions. Artistically, it renders music that is between pop culture and music as art. The range of musical variety is wide. On one side of the extreme, we find styles like kudoro, kwaito, baile funk and nortec, which some scholars call global ghettotech (Marshall, 2009). These styles are to a certain extent an updated version of what Eshun calls afrofuturism (Eshun, 1999; Goodman, 2010). On the other extreme, we find artists working in such genres as free improvisation, musique concrète and glitch (Prior, 2008; Kraut, 2009). These artists deal with concepts like anti-Orientalism and alternative modernity, and they are as close to Futurism as they are to afrofuturism. Politically however, these musicians often do not believe in big political ideas anymore, and they often do not present direct politics in their music. The Lebanese musicians, for example, do not feel close to the leftist protest singers of the Lebanese Civil War, like Marcel Khalife, Khaled al-Habre or Ahmad Qaboor. If anything, they prefer the Lebanese singer and musician Philemon Wehbe who during the Civil War released a cassette with the song, «Lebanon, They Fucked You All».

In addition, the new avant-garde is no longer interested in the clear divisions between the so-called first and third world. They network and collaborate freely with musicians in Europe and the United States as equals. In my last Skype conversation with Atoui, one of his sentences really stuck with me. On my own network, www.norient.com, I perform the piece «Sonic Traces: From the Arab World», an audiovisual journey through sounds, music and noises from the Arab World. Three Swiss (including myself) play on stage, and sometimes a guest from the Arab World (for example, Raed Yassin) plays with us, whenever an organizer can afford the airfare. Tarek Atoui told me to contact Sharif Sehnaoui to perform at the 10th Irtijal Festival for Improvised Music in Beirut. We intend to do so, most likely in 2011; however, we are a bit worried. Three Swiss people talking to an Arab audience about music in the Arab World, Will this work? «Don’t worry», Atoui told me directly, «We create our music in transnational niche circles, beyond nationalities. You are one of us.»

Tarek Atoui and his colleagues in Beirut represent the new avant-garde of the 21st century. They challenge the Euro-and US-centric views of innovation in music, and are part of Music 2.0 niche networks. They create music in small studios, rather than in big radio studios like those from the earlier avant-garde. Their music speaks from a specific, non-Eurocentric position, and does not come with political or artistic manifestos. It is not Futurism, nor is it afrofuturism, and it is often unstable and not always clear in its focus. It is searching to find transnational artistic positions beyond Orientalism, consumerism and propaganda.

After a brilliant and moving concert with the Staalplaat Sound-System at the Transmediale Festival in Berlin in 2008, Atoui was very angry. «We fucked up, we lost control», he told me unhappily after the performance. This is what today’s world is about, I thought. We are surrounded by information, by war, by terror and by an enormous volume of media sources. One could argue that Atoui creates the soundtrack of the 21st century, which would fit with Anthony Storr’s idea that music is an attempt to «create sense out of chaos» (Storr, 1992). According to him, music is not an escape from «real» life, but rather a way of ordering human experience. At least Atoui and some of his Beiruti colleagues seem to come closer to the cry of the Pop Art generation: Art is life and life is art.