Since hip hop’s birth, samples of politicized words have resonated across genres, be it punk anti-establishment, jaunty new-wave experimentations, or EDM’s uplifting calls for unity. We even find producers quoting samples that plainly go against their values, and those of dance music as a whole. In doing so, they can reclaim, stylize, and expose a message to their own agenda. In the following examples, writer and event planner Lola Baraldi traces out music that gives political words a new meaning through distortion, cutting and pasting, amplification, and camouflage. These approaches, Baraldi argues, break out from traditional modes of social commentary and denunciation, often taking the shape of danceable satire.

Mockery

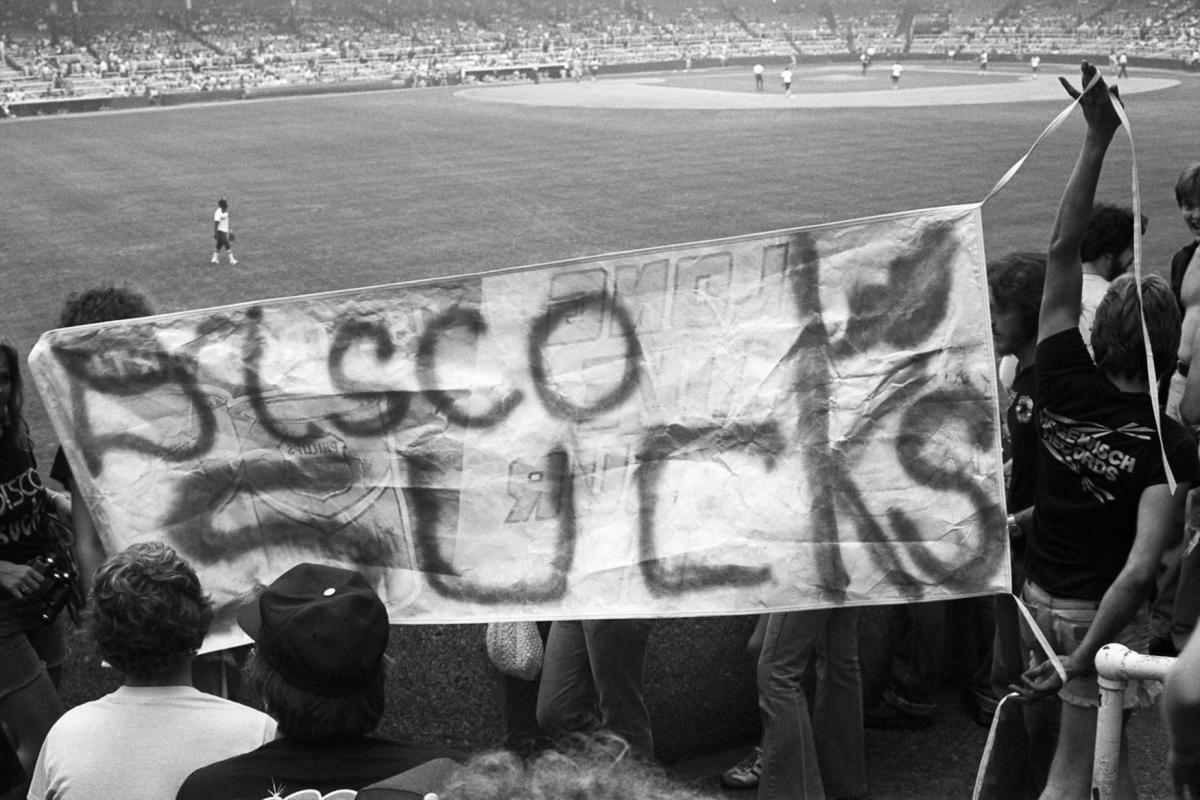

Al Kent’s «Disco Sex» starts unexpectedly. «Why did they get all hyper?» questions a woman between TV static noise cuts. «Well they wanted to blow up all the disco records, they don’t like ‘em», answers a matter of fact tone. The exchange is followed by broadcasts covering the infamous Disco Demolition Night of 1979. The intro reaches its crescendo when anti-disco spokesperson Steve Dahl blares out «Disco sucks»; jeers are picked up by the crowd in unison, before they set thousands of black music records on fire. The sound bite fades into a drum shuffle, a muffled funk bass, and other signs of an unmistakable disco-house track.

Why would the founder of a label called Million Dollar Disco begin a song celebrating a broad range of black music genres by recounting this discriminatory event? Dark comic irony comes to mind. Kent enlists cheery music to remind us of the contradiction between a destructive call to action and a genre that only ever celebrated unity and inclusion.

Electronic music’s wide range of available effects to inflate, distort, veil, and contrast a message give the producer a transformative range of interpretive tools. Danceability allows this departure from the original context to be playful – even when the message is sobering.

Re-Contextualization

Video further extends parody and commentary. In «Destroy Rock n’ Roll», Mylo samples Church Universal and Triumphant’s «Invocation for Judgement Against and Destruction of Rock Music». From Duran Duran to Tina Turner, the mantra condemns artists held responsible for «perverted movements of the body». The sample finds itself overlapped onto a groovy house beat, in a music video where Mylo casually stencils the names and portraits of the accused. In this new setting, the listing and its inclusion of several non-rock and roll and mispronounced artists takes a turn for the ridicule.

Artists gain a form of control when they displace a message’s meaning beyond the intended scope, interpretation, and space of diffusion. By de-contextualizing and embedding it into their own worldview, artists disrupt the original message’s source of power. Mylo’s re-appropriation of the New Age Church’s words into his own audio-visual packaging transforms the denunciation into an upbeat parody.

Collage and Commentary

This power of de-contextualization through sampling can help the artist regain a sense of ownership on a narrative in which they have a deeply rooted stake. Felix Laband took ten years to assemble Deaf Safari, an eclectic album surveying South Africa’s complex past and present: «When people think of Africa (…) they see it as a colonial safari adventure. People think there’s lions running around the street and all that. So [the album] is a comment on that, the unreality of the reality of Africa», he specified on Popsicle TV (2016).

Deaf Safari imaginatively assembles documentaries, speeches, kwaito music, chain gang work songs, church sermons, and activist American folk. The loops, edits, and sound collages support Laband’s role as a citizen exploring historical and emotional narratives. The snippets of life weaved into the album vary in seriousness, from playful to poignant, or ambient to political, as seen in the song «Ding Dong Thing». In an Al-Jazeera interview, when prompted about corruption accusation cases threatening his upcoming campaign, South Africa’s ex-president Jacob Zuma articulates «as you know there’s been almost a ding dong thing in this case (…) it is unprecedented that a person has been pursued, the way Zuma has been pursued» – referring to the legal back and forth (Al Jazeera 2008). Laband’s track «Ding Dong Thing» takes the saying and applies a filter and pitch change, isolating and unrooting it into a peaceful track. Suddenly, a world leader’s juvenile choice of words to unpack allegations of deeply-rooted corruption becomes quizzical. The message is dissonant and disrupted, its inconsistencies softly highlighted.

Comic Juxtaposition

Comic juxtaposition, an elaborate form of satire, gains a seamless home within the possibilities of sampling. Some of the most easily findable songs that sample politicians are recordings of American or British conservatives, slapped onto basslines. The words become ironically integrated into a sound that historically has been progressive. Some artists take it further through re-arranging political words to express a story they find truer, or funnier.

Hip hop mashup artists Steinski & The Mass Media kick off the theatrics of «It’s Up to You (The Television Mix 1991)» with George H. W. Bush announcing the deployment of troops in Iraq and Kuwait. The speech is immediately layered onto the familiar two-note riff of Buffalo Springfield’s «For What It’s Worth», a protest song legacy. Bush’s speech is edited into a funky call and response rhythm, his words cut and pasted together:

I am certain our cause is just – a gallon of gas,

I am certain our cause is moral – loss of life – and

I am certain our cause is right – big money, money.

Then comes a «new world order» drawl, comical in its stretched effect. This slicing and matching help debunk what Steinski & The Mass Media read between the lines. The track’s upbeat nature juxtaposed with words that carried such bloody ends flirts with the grotesque, another feature of satire.

Framing Activism

When the original context of a message is accepted and preserved by the artist, music helps diffuse it’s reach. Taking words that are already satirical and framing them with a fitting sound is a resourceful way to expand their power. The producer’s chosen role here is to amplify a voice and its revindications by deepening the mood around it.

In «Jalel Brick Rrumi», Tunisian artist Deena Abdelwahed throws down social critique amidst a frenzy of electric oud and industrial rolls. Emboldened by repression, the track features biting sarcasm from Jalel Brick, a Tunisian cyberactivist known for his blunt online cursing of the authorities.

Deena Abdelwahed mixes Brick’s unedited, raw words into the track’s foreground, while associating him with Persian wordsmith Rumi in the title. Distortion occurs not in the sound bite itself, but in the harsh noises that frame it. Satire is present in content over style, as an extension of activism.

Mind and Matter

When both style and content voice a denunciation, it makes for a singular channelling of frustrations. Reactions to Brexit have seen their fair share of representation throughout UK dance music, from the frantic, high-BPM tracks of Yuri Suzuki’s «Acid Brexit» to Perc’s textured Bitter Music EP.

In Bitter Music’s first track, «Exit», we can hear David Cameron’s resignation speech in the background. His words are faint, buried in morose and crunching soundscapes. This form of sound design evokes a wish to block out what is undeniably a political reality.

Power in Production

Ultimately, satire through sampling is not meant to be the strongest means of activism. Acts like Underground Resistance demonstrate that wordless techno can be the most powerful of political commentaries. The militant Detroit collective has a long history of rejecting commercial and societal norms, without resorting to reclaiming someone else’s message, but rather magnifying their own.

Yet there is power in re-appropriating a message to a new source, tone and space, even without intention or guarantee that all listeners will understand the process of disruption. The constrained yet explorative structures of dance music allow for a distinct play between subtlety, groove, and revindication. Words and mood woven into the producer’s own patchwork of perception can redirect a certain point of view towards an audience it wasn’t intended for, and give the artist ownership of a narrative that concerns them. If not a political shift, this can surely push critical thinking through alternative and sonic storytelling.