Needling Nostalgia: The Then and Now of Delhi’s Independent Music Scene

A personal essay in which the author interrogates the musical milieu of the past through the lens of the present. Through reflections, quotes, references to archival material, and a drift through memoryscapes, the author reflects upon the transitional entity of the music scene in the city of Delhi, which he has witnessed from the 2000s all the way till now, reflecting on what was «popular» or «headlining» at various points. The need to step out of nostalgia when thinking of musical communities of a bygone era underscores the essay as it draws upon other characters and people who enter, exit, and contribute to the scene that is always on the cusp of its next transformation.

In the early 2000s, the Delhi scene was a very small bubble defined by its counter-cultural positioning vis-à-vis the mainstream and perched on the shoulders of a fairly straight-forwardrock/metal sound that lumped various genres together. Live shows meant familiar faces, a sense of community/identity, and a shared sense of optimism over the potential of what was happening. Bands were still playing cover-heavy sets peppered with a smattering of their own songs (also referred to as «self comps») and I had just started dreaming of becoming a music journalist. In fact, the arrival of electronic rock or electronica or «guitar with laptop» was the dawn of something new and it still feels like two summers back.

This is why, of all the ways that time has curdled, saying «Linkin Park is classic rock» is the sourest: it places the music of our youth in the same pantheon as the music of our parents’ youth, which has rightfully turned members of what a friend called the «OG1 rock scene» into greying grumps. Put a bunch of us into a room and chances are that one might get stuck in a loop of reminiscing the good ‘ol days. Musical memories are related to knowing who we are, but nothing makes me grumpier than lingering too long in the hallways of reminiscence, largely because it comes in the way of appreciating a present that is markedly better in many ways.

The GIR Era Deep Freeze

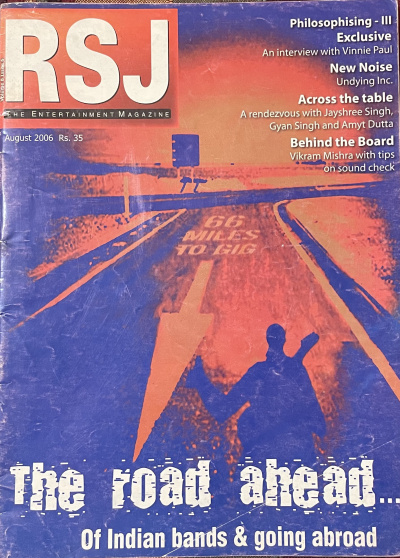

These good ‘ol days can largely be defined as the era of the late Amit Saigal, one of the earliest and most iconic patrons of the music scene, fondly called Papa Rock by us bright-eyed upstarts. He was the founder of Rock Street Journal, which began as an informal newsletter for bands and grew to become a magazine and events company that nurtured the scene. It sponsored college fests, coaxed pubs into hosting bands on certain nights, and organized its own rock festival (Great Indian Rock aka GIR), which was a gateway for cultural exchange between bands from India and Norway.

Along the way it bolstered a sense of legitimacy. I got my first job as a writer and editor, and soon enough, we were featuring bands from across the country on the cover. It laid down the groundwork for corporate patronage and encouraged many others to look at the independent music scene as more than a transitional phase between going to college and getting serious in life. But it didn’t prepare me for today, a time when every day is the 20th anniversary of something, which in turn seems to reinforce that at this point, memories are all we have. And as definitive as these memories are, they seem to suggest that things just stopped or froze there. But they didn’t, they just changed. And that’s not completely a bad thing.

The Digital Turn or Just Another Fad?

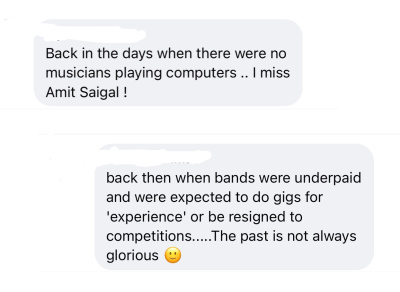

A lot of this division between then and now seems to (incorrectly) rest on an analog versus digital divide, which is owed to the sudden rise in the popularity of EDM2 as the new commercial pop sound of the 2010s. EDM elbowed out live bands with multiple instrumentalists from venues because promoters realized that the booking costs for EDM were lower (personnel and equipment costs dropped) and the crowds higher. This created a kind of antagonism towards any and all kinds of electronic music and discounted any craft or artistry associated with producing this music. The computer (or the laptop) was suddenly the enemy, and anyone who produced or performed electronic music was painted with the same brush of «button pusher». I don’t remember the exact year, but I do remember the often-heard words, «I thought the laptop was just another fad». Nothing summed up disappointment better than this phrase, but to constantly hark back to a time when «musicians didn’t play computers» really pisses me off on behalf of computers, because what computers did is much more than popularize dance music – they made music production accessible. In doing so, the computer also opened up the scene for a lot of musicians who were not making generic four-to-the-floor dance music or just pressing play on consoles.

One of Delhi’s biggest exports, Skyharbor – a prog-metal band with transatlantic members – was kickstarted by a bedroom producer. Keshav Dhar, the founding member, started writing and recording djent (a subgenre of metal), which blew up over the internet and attracted a lot of interest from musicians across the world. Soon, Marty Friedman (ex-Megadeth) reached out to him for a collaboration, an epochal moment for a scene where many idolized Megadeth. Keshav had arrived.

But it didn’t stop there, Skyharbor was to soon become a five-member touring outfit with multiple shows and stints across Europe and America. It was a step forward from cultural exchange programs, and a quick Google search will tell you that they have played some big stages across the world. In fact, as I type this, Peter Cat Recording Co., just completed their tour of America and announced their dates for Europe; an Instagram notification on my phone is suggesting that I watch two bands, Crocsak and Time Throttle. I can assure you that the laptop has enabled each of these bands to record or perform their music in one way or the other.

How Many Exposures Does It Take to Pay the Rent?

In its nascent stages, the scene wasn’t really a viable option if you were looking to get serious about a career. Bands barely made any money, were often asked to play for «exposure» (a common joke that implied that getting seen was more important than getting paid), and many musicians had to quit making music or just work with film music directors. Today, the number of musicians who believe they can survive by sticking to their sound or carving their own path is a sizable number.

At its youngest, the scene was an affirmation of our anglicized tastes and gave us an identity;along the way, it has also nurtured careers, from producers and managers to touring/production support. In fact, one of Delhi’s most interesting exports is a bilingual metal band called Bloodywood. The band has played only 14 shows in India but has played close to a hundred shows worldwide, including Japan. Their mix of Punjabi, Hindi, and English with Indian instruments and heavy metal chugs is unapologetic, and they have a rabid global following. What they don’t have is side jobs or main jobs; they’re just one band amongst many others who are not afraid to test the waters of being full-time musicians.

This Is Not a Throwback

The scene is now many scenes, and much like the rest of India, hip hop has gained prominence. A close look at 2022’s list of releases compiled by journalist Amit Gurbaxani (Indian Music Charts Podcast) reveals that 36 out of 82 releases from Delhi in 2022 were hip hop. That is 43.9 percent of all releases. The hip hop scene in Delhi is conspicuously Hindi, and thus, significantly different from the rock scene. In keeping with the roots of the genre, it has embraced within its folds themes of socio-political justice. Hip hop as we’d known it earlier was largely co-opted by Bollywood, and the Punjabi rap scene was basically about churning out party anthems that were themed along the lines of bling, girls, and machismo. Today, hip hop is far more exciting than that and includes varying perspectives and demographics, and much like metal, is the voice of angst and assertion. The music scene of the early 2000s was about finding a space – albeit well-defined and self-conscious – outside the narrow fit of the mainstream. In 2023, it is a space that is far more comfortable with its evolving identity.

I’d be lying if I said that I don’t miss some of the bands I loved and heard. I miss them even more because many of their songs hadn’t been recorded for posterity. Perhaps, if we had more songs, we wouldn’t have to relive those moments at the expense of the present. And yet, even that feels so transitory now. Over the past two weeks, I’ve found myself at three different gigs – one metal, the other blues, and the third reminiscent of 1980s synthpop – and to label each of these gigs as a «throwback» is a denial of the present that contains much more than one kind of sound or aesthetic.

So much of this is the future that I had longed for during the good ‘ol days (and a lifetime of security and stability as a music writer but I guess this will do for now) that reminiscing the past constantly feels like betraying my younger self who just wanted the scene to grow in a way that nourishes and includes. I was never going to be the main character; at best, I’d be almost famous.

This essay is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Delhi», curated and edited by Suvani Suri.

Project Assistance: Geetanjali Kalta

Graphics/Visual Design: Upendra Vaddadi, Neelansh Mittra

Audio Production: Abhishek Mathur

Video Production: Ammar

Biography

Shop

Published on September 29, 2023

Last updated on February 21, 2024

Topics

Digitization means empowerment: for niche musicians, queer artists and native aliens that connect online to create safe spaces.

From the music format «78 rpm», the melancholic echoes of a dubbed out rave night in London, and parodic mockings of «perfect house wifes» by female Nigerian pop musicians.

From Korean visual kei to Brazilian rasterinha, or the dangers of suddenly rising to fame at a young age.

Special

Snap