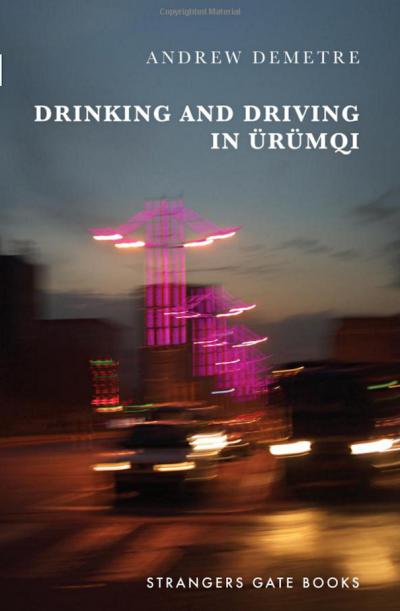

Radio Discostan’s Arshia Haq interviews travel writer and monologist Andrew Demetre on his travel memoir Drinking and Driving in Ürümqi and his project Radio XUAR. Radio XUAR delivers a live freeform musical journey to Xinjiang Province, Far Western China, presenting rare and hard to find Uyghur music ranging from the deeply traditional, to rock, U-pop, neo-psychedelic, opera, hip-hop, the rich musical landscapes in between, plus behind the music stories and legends about Uyghur musical artists’ struggle to squeeze their expression through the filters of the CPC (Communist Party of China). Read also a small excerpt from Andrews travelogue below.

«Aziz’s Land Cruiser was a superior ride – a Shangrila on wheels. Outside it was as tough as a tank, but once inside, it gave you the impression of being in a high-tech marshmallow. It was a welcome relief from the tiny, unsafe-at-any-speed, street-scraping tin can Rihangül’s family and I had been careening around in over the last few weeks – the music cranked, seven people distracted by song, not one eye on the road, no airbags (too expensive), not one seat belt fastened (bad luck), fueled by propane (the tank was bolted down right behind me), chance, and prayers, playing chicken with the hordes of offensive drivers jamming the city’s network of roads and uncontrolled intersections, and dodging everything in sight from coal trucks, buses, taxis, bicycles, bean readers (Xinjiang-style fortune-tellers), schoolchildren, police, and the swarms of rickety tuk-tuk contraptions carting loads of jiggling, unsuspecting, deliciously fat-assed sheep to their demise.

Our current vehicle was not that ride, and it turned the usual unhinged experience of driving in Ürümqi into a pleasure: quiet, powerful, pampering you in its slick leather interior with buttery, body-gripping seats, and protecting you with multiple airbags and a bump-eating suspension (as opposed to a bone-on-bone, nonexistent one) behind tinted – I assumed – bulletproof glass. The SUV’s state-of-the-art surround sound system pumped out Uyghur Pop. The ubiquitous local genre juxtaposed ancient instruments with cutting-edge electronic ones and had its own Vegas-like star system replete with flashy, ’70s Elvis-inspired silk and polyester stage costumes. U-pop blasted from every cd shop, and it had grown on me – an unrepentant pop-hater – with its frenetic mix of earthy tradition and synthesized modernity. Dramatic, heartfelt, unaware of its own nostalgia, the music was kitsch but not old-fashioned, and its lyrics writhed with love or sadness, seldom stewed with anger or revenge, never spoke of revolution, and throbbed with arresting beats below the soulful, tight-lipped cries of its singers. It was what remained after more traditional forms, often viewed as rebellious, were consumed and digested by the Party’s censors. Buoyed by U-pop, the four of us floated untouchable across Ürümqi’s cutthroat traffic in our low-altitude Kevlar blimp.

I glanced around at the telling faces of my hosts. Ahmat, Aziz, and Rihangül were Uyghurs, the indigenous people of the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria, a people with deep, centuries-old, Buddhist-then-Muslim roots in the Turkic soils of the region, alongside other Central Asian peoples – Kazakhs, Tatars, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Kyrgyz. The Uyghurs had unified under the pressures of history, military campaigns, territorial feuds, and more recently, land grabs, demolitions of their homes, disparate hiring practices, racial profiling, and disappearances – among sundry other oppressions perpetrated by the Han-dominated Communist Party and its Beijing-controlled police state. They tolerated the encroachment of the modern Han hordes from the east on their own ancient land, as it was renamed and reinvented out from under them by Beijing as Xinjiang, the «New Dominion». I sensed Aziz, Ahmat, and Rihangül had in one way or another suffered under the weight of that jagged, bloody history. It was the fiber holding the Xinjiang Uyghurs together, and I already felt it winding around my hubristic sense of individuality. An evocative breath captured the essence of this suffering: a deep, resolved exhalation I had in recent days dubbed ‹the Uyghur sigh.› I heard Uyghur sighs everywhere.»