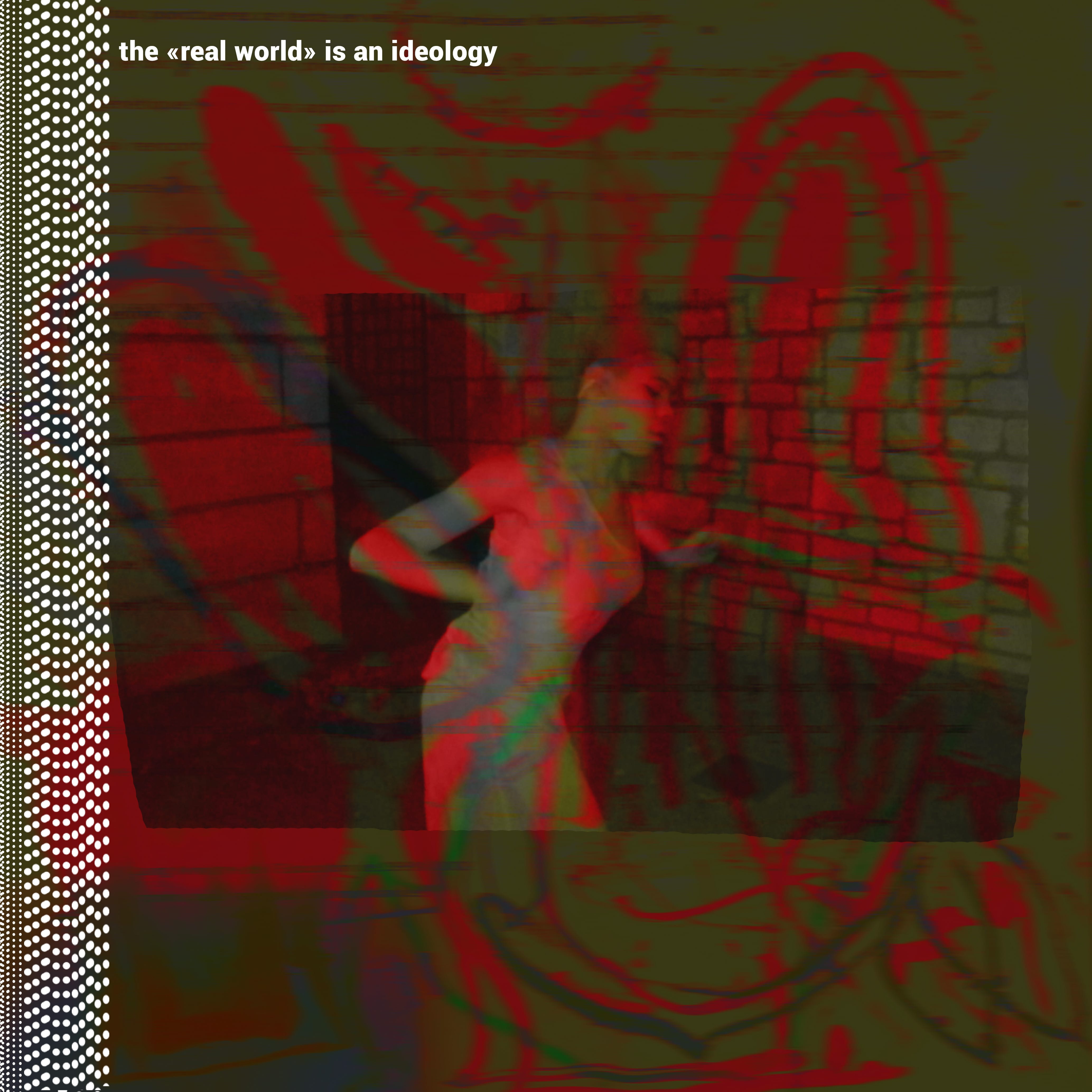

«Real World» Problems

Eden Tinto Collins’ and Giuliano Ponturo’s short film CoNEC (France 2019), and artist Amanda Melissa Baggs’ role in it, reminds Philipp Rhensius of his own childhood experiences. An essay about the epiphany that communication goes far beyond the verbal, and how the «real world» is often revealed as conformity.

→ Check all articles of this special

→ Download PDF with introduction and table of contents

As a child, I barely spoke. I was very shy and anxious – and a favorite foe of my class teacher, who was into mental and physical abuse. He would often ask me what one plus one was. He knew I knew the answer but that I wouldn’t dare to say it out loud. He would then either make fun of me, pull my ears, or force me to stand in a corner until the end of the class. The worst thing about it was not the humiliation, but being incapable of defending myself. I learned that if you can’t talk about it, it is not real. I was a boy stuck in his «own world», failing to reach out to the «real world».

Instead of making an effort to communicate with this «real world», I built my own realities, mostly with books and music. The mosh pit at a hardcore concert, or the dancefloor at a rave, was rarely based on language but on affect and a tacit knowledge that only required a shared experience. Thus, as a person for whom a guitar riff or a percussion pattern was more «real» than anything, I was barely understood.

Worlds Within Worlds

Today, I still live in my own worlds. Reading poetry or dancing to dubstep still feels more real than going to the supermarket. Yet, in the meantime, I compromised. I managed to dig holes into the «real world», and obeyed the functionality of language in order to make a living. As a white person living among a white majority, it was simple. I just adapted to the default mode of being a citizen.

Watching the short film CoNEC by the Black French artist Eden Tinto Collins and Giuliano Ponturo, I was reminded that my quasi-outcast life is a privilege: It is chosen, not assigned. Collins’ film is based on the video essay In My Language by the artist Amanda Melissa Baggs, a genderless nonverbal person with autism. In the film, Baggs plays with the knob of a drawer or rubs their hand against a book. Later, a synthesized voice claims that Baggs’ language is not about designing words or symbols, but «being in a constant conversation with every aspect of my environment».

Communication Beyond Words

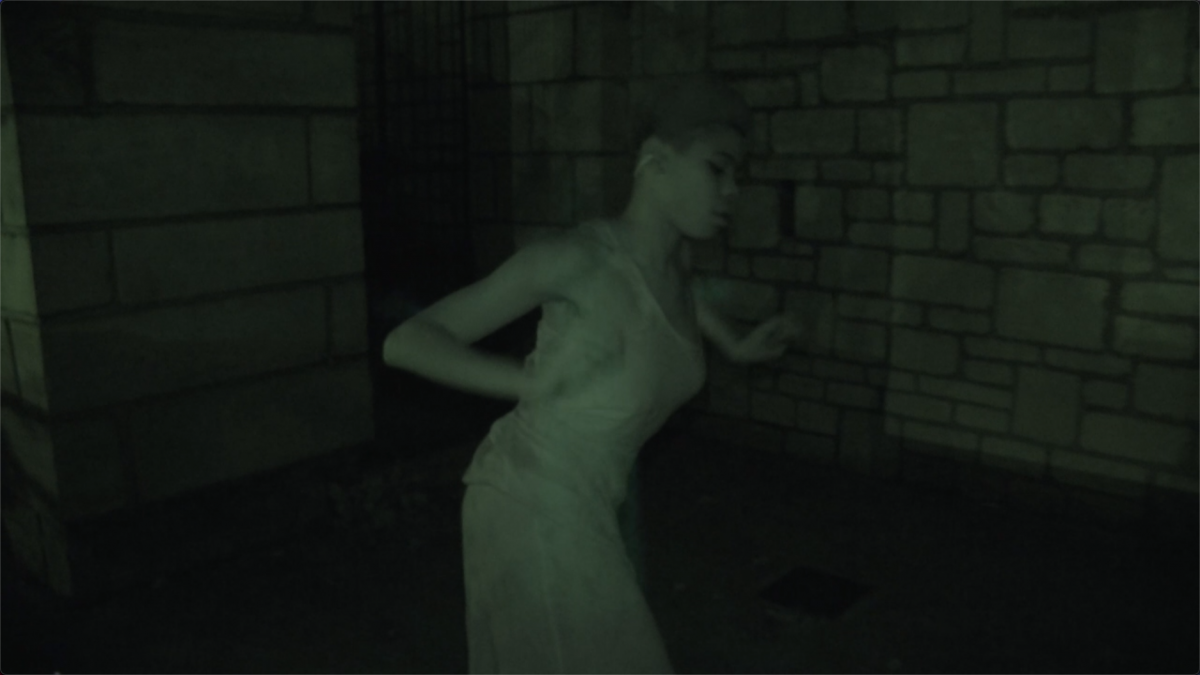

While Baggs refers to nonverbal people, Collins and Ponturo applies the issue of not being heard to the context of being a Black person among a white majority. Collins, filmed through a night-vision device which conjures an uncanny aura, finishes with one of Baggs’ core claims: «It is only when I type something in your language that you refer to me as having communication.»

As somebody whose outcast life is chosen, not inherited, I don’t equate my life to those of marginalized groups or people like Baggs. But keeping in mind my temporary mutism in primary school, I can at least comprehend a life that is driven by something beyond words.

Baggs’ famous video lays bare a very recent political problem: The need to recognize people individually, not universally, to meet a basic condition for justice. But there’s more at stake than this judicial issue. As Baggs’ way of world-making is barely understood by most people, Baggs is not just excluded from participation but also from enriching the world with different forms of being and doing. Silencing other people’s communication is an attempt to defend a world that is prefabricated and based on representation, against one that is in a constant state of becoming.

Intuitive Cognition

Baggs’ mode of making sense of the world seems alien to the «real world» because it is based on a different, more intuitive cognition rather than an intellectual one. By highlighting the need «to type something in your language» in order to be intelligible, Baggs exposes the limitations of verbal language, and the ways it makes the world smaller than it could be. Baggs reminds us that the words one uses are often like an automatic consultation of some previously, carefully defined space of possibility. Tell me what one plus one is, and you will have a happy life.

Sometimes, I feel I was intuitively doing the right thing by not reacting to my teacher’s provocations. By refusing to recite that one plus one equals two, I saved myself from the «real world’s» lack of imagination. With their relentless activism, Melissa Baggs reminds us that the «real world» is actually an ideology. And its worst enemy is that which doesn’t have a word yet.

The short film «CoNEC» by Eden Tinto Collins and Giuliano Ponturo was screened at this year’s online edition of the Norient Film Festival 2021 as part of the F.r.iction Show by Eden Tinto Collins and Gystère. See full program here.

This text is part of Norient’s essay publication «Nothing Sounds the Way It Looks», published in 2021 as part of the Norient Film Festival 2021.

Bibliographic Record: Rhensius, Philipp. 2021. «Editorial: NFF 2021 Essay Collection.» In Nothing Sounds the Way It Looks, edited by Philipp Rhensius and Lisa Blanning (NFF Essay Collection 2021). Bern: Norient. (Link).

Biography

Links

Published on January 30, 2021

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topics

On new cultural implications of Meme Music, and how commnunication is more and more a result of power relations disguised in social networks.

What is «Treble Culture»? How does what one hears affect what one sees?

Snap