New Delhi at 33.33 RPM

Music archivist, record collector, and selector DJ Nishant Mittal, also known as Digging in India, carefully picks out vinyl records from his collection and narrates the tales that they hold about the capital of India, New Delhi. Nishant compiles this photo series by carrying five specific records from his record collection to historical landmarks in the city, through which he documents their intertwined stories.

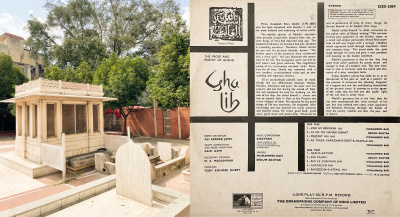

Various Artists: Ghalib – Portrait of a Genius

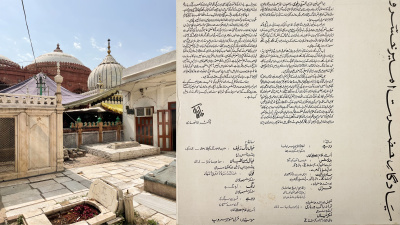

Mazar-e-Ghalib, Nizamuddin, New Delhi

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib (1797–1869), born in Agra, India, was a poet in Urdu and Persian languages. Ghalib is considered to be one of the greatest literary figures of the Urdu language. He spent most of his life in Delhi and this is where much of his work was written.

Portrait of a Genius was an album released in 1968 on India’s His Master’s Voice label. The album is a coming together of legendary artists from diverse fields who combined magisterial creative forces to create this masterpiece. The sleeve notes are written by Ali Sardar Jafri and narration is done by Kaifi Azmi. Ghalib’s poetry has been sung masterfully by Begum Akhtar and Mohammed Rafi, and music has been composed by Khayyam.

On a blazing hot summer noon I took this record out from my collection and photographed it at Mazar-e-Ghalib – the tomb of Ghalib. The building next to the tomb is Ghalib Academy – a museum, art gallery, and library dedicated to Ghalib. A short walk away is «Ghalib Kabab Corner», where you find the most exquisite mutton kebabs – a meat preparation, minced and cooked with spices and condiments that has multiple variations across the Middle East, West, and South Asia.

I have digitized my favorite track from this record: «Ye Na Thi Hamari Qismat» by Begum Akhtar. The «Mallika-e-Ghazal» (queen of ghazals) sings the poetry of Ghalib, a match made in heaven. Agha Shahid Ali, the New Delhi born poet wrote this as a tribute to the singer Begum Akhtar in 1974 after her passing (Gupta 2021):

Do your fingers still scale the hungry

Bhairavi, or simply the muddy shroud?

Ghazal, that death-sustaining widow,

sobs in dingy archives, hooked to you.

She wears her grief, a moon-soaked white,

corners the sky into disbelief.

You’ve finally polished catastrophe,

the note you seasoned with decades

of Ghalib, Mir, Faiz:

I innovate on a noteless raga.

Various Artists: The Multifaceted Genius of Ameer Khusrau

Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah, Nizamuddin, New Delhi

Time for yet another record and another landmark. After I leave Mazar-e-Ghalib, I make my way to Hazrat Nizamuddin Dargah, which is the Sufi saint Khwaja Nizamuddin Auliya’s dargah. A dargah is a shrine or tomb built over the grave of a revered religious figure, often a Sufi saint or a dervish. This dargah complex has more than 70 graves, including that of Abu’l Hasan Yamin ud-Din Khusrau (1253–1325 AD), better known as Amir Khusrau or Ameer Khusrau, who was the spiritual disciple of Saint Nizamuddin.

Ameer Khusrau was a Sufi singer, musician, poet, and scholar who lived during the period of the Delhi Sultanate. He was a mystic and a spiritual disciple of Hazrat Nizamuddin of Delhi, India. He wrote poetry primarily in Persian, but also in Hindavi.

Khusrau is said to be the one responsible for introducing the ghazal style of song in India, and is also considered to be the founder of qawwali. Both are popular genres in India and Pakistan.

While Khusrau could bravely stand the loss of his mother and youthful brother (1299 AD) and continue to compose poetry, he could not bear the loss of his spiritual mentor, the 92 year old Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia. He burst out with only one doha and later the same year, followed in the footsteps of his Master to the heavenly abode.

(Excerpt taken from the liner notes on the sleeve of the record written by Dr Zoe Ansari.)

Khusrau and Hazrat Nizamuddin rest close to each other in the dargah complex, staying close even on the other side. I have digitized the doha1 «Nizamuddin Peer Auliya, Chakwa Chakwi Do Jane», written by Khusrau for his mentor Nizamuddin, and sung by the Indian classical vocalist Ustad Ghulam Mustafa Khan on this record.

Sharan Rani: Sarod Solo

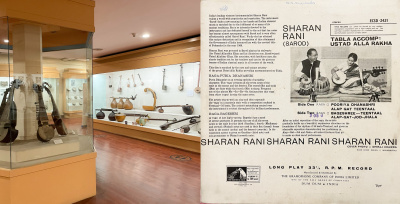

Sharan Rani Gallery of Musical Instruments, National Museum, Janpath, New Delhi

The sun has now started to fade and I catch an auto-rickshaw to make my way to the National Museum in Janpath, New Delhi. Founded on August 15, 1949, the museum has one of the largest collections in the country, housing over two lakh artifacts that embody the vast and layered artistic and cultural histories of the subcontinent.

My visit focused on the museum’s Sharan Rani Gallery of Musical Instrumentals. Sharan Rani, also known as the «Queen of Sarod», was an Indian classical sarod player and music scholar. Born in 1929 in Delhi to a conservative Hindu family of well-known businessmen and educators, Sharan Rani learned to play the sarod from the master musician Allauddin Khan and his son Ali Akbar Khan.

During her lifetime, Sharan Rani collected over four hundred obscure and rare musical instruments with a vision to build a collection that would help the future generations learn about the rich musical heritage of the country. Rani donated her entire collection to the museum in three installments – first in 1980, then in 1982 and 2003. I exit the National Museum silently applauding Sharan Rani’s vision and commitment to collecting, having discovered and learned about instruments that I had no encounter with previously.

The Beatles: Abbey Road

Rikhi Ram Musical Instruments, Connaught Place, New Delhi

Now it’s time to catch another auto-rickshaw to make my way to the next landmark, the iconic Rikhi Ram musical instruments shop in Connaught Place, the central market built during colonial rule.

A lot is known, written, and talked about The Beatles’ spiritual journey in Rishikesh during February 1968, but not many are aware that the Beatles had made another stop in India two years prior on July 7, 1966. After touring all across Japan and the Philippines, on their way back to England the Beatles stopped in New Delhi for a day. The band had hoped for an easy day of sightseeing in the capital city, but they were greeted by over 600 manic fans at the airport and their hotel, eager to catch a glimpse of the fab four. This was Beatlemania at its peak!

During their day-long stay in Delhi, they explored and bought classical music instruments specific to the region from Rikhi Ram, a music aficionado and owner of the music shop located in Connaught Place. After their pitstop, the band flew back to England the next day with a few eclectic instruments added to their arsenal.

George Harrison in his autobiography would later say:

«Before the tour was planned, I had an arrangement made that on the return journey from the Philippines to London I would stop off in India, because I wanted to go and check it out and buy a good sitar. I had asked Neil [Aspinall, tour manager] if he would come with me, because I didn’t want to be in India on my own. He agreed, and we had booked for the two of us to get off in Delhi.

Somewhere between leaving London and going through Germany and Japan to the Philippines, one by one the others had all said, ‹I think I’ll come, too›. But we got to Delhi and, after the experience in the Philippines, the others didn’t want to know. They didn’t want another foreign country – they wanted to go home.

I was feeling a little bit like that myself; I could have gone home. But I was in Delhi, and as I had made the decision to get off there I thought, ‹Well, it will be OK. At least in India they don’t know The Beatles. We’ll slip into this nice ancient country, and have a bit of peace and quiet›.

The others were saying, ‹See you around, then – we’re going straight home›. Then the stewardess came down the plane and said, ‹Sorry, you’ve got to get off. We’ve sold your seats to London›, and she made them all leave the plane.

So we got off. It was night-time, and we were standing there waiting for our baggage, and then the biggest disappointment I had was a realization of the extent of the fame of The Beatles – because there were so many dark faces in the night behind a wire mesh fence, all shouting, ‹Beatles! Beatles!› and following us.

We got in the car and drove off, and they were all on little scooters, with the Sikhs in turbans all going, ‹Hi, Beatles, Beatles!› I thought, ‹Oh, no! Foxes have holes and birds have nests, but Beatles have nowhere to lay their heads›.»

(The Paul McCartney Project 2022)

I briefly explain my photo series concept to the third generation owner of the shop, Ajay Sharma, and ask his permission to click pictures of his shop. He graciously approves. I draw out my vintage copy of an Indian pressing of Abbey Road2 and photograph it. Two tracks from this album «Mean Mr. Mustard» and «Maxwell’s Silver Hammer» were written in Rishikesh in 1968. The store staff are repairing sitars while I am there clicking pictures, trying not to disturb them. Thanks to Mr. Ajay’s generous support, I get done soon and head off towards the next site.

S. Hazara Singh: Film Tunes on the Electric Guitar

Qutub Minar, Mehrauli, New Delhi

The main reason for me to purchase this record was the back sleeve that featured a suave looking Sikh gentleman holding a double neck steel guitar in front of the Qutub Minar, the quintessential historic marker of the city of Delhi.

Built in the early 13th century a few kilometers south of Delhi, the red sandstone tower of Qutb Minar is 72.5 meters high, tapering from 2.75 meters in diameter at its peak to 14.32 meters at its base, and alternating angular and rounded flutings. Qutbu’d-Din Aibak laid the foundation of Minar in 1199 AD for the use of the muezzin to give calls for prayer and raised the first storey, to which were added three more storeys by his successor and son-in-law, Shamsu’d-Din Iltutmish (1211–1236 AD).

How can you stumble upon such a record and not take it home with you? The music on the record is of a very common yet forgotten genre from the 1960s to the 1990s – instrumental versions of popular Hindi film music (Bollywood), which almost sounds like elevator music/Muzak. There have been many artists who released instrumental versions on the guitar such as Batuk Nandy, Sunil Ganguly, Charanjit Singh, Kazi Arindam, Van Shipley, Dipankar Sen Gupta, and Rajat Nandy, but no one comes close to the artistic finesse and swagger of S. Hazara Singh.

Hazara Singh was a studio musician working in troupes of various Indian music directors, but was most preferred by O.P. Nayyar. Even though you may not have heard Hazara Singh’s name, you most definitely have heard his music before. He most famously played the guitar on the iconic swinging Bollywood tune, «Mera Naam Chin Chin Chu».

The inclusion of the Qutub Minar on the sleeve remains a mystery to me: was Hazara Singh from Delhi? Did he love the Minar? Or was it just added for aesthetic purposes to keep the swagger intact? Guess we’ll never know!

- 1. A doha is a couplet consisting of two lines, each of 24 instants (maatras). The rules for distinguishing light and heavy syllables are slightly different from Sanskrit. Each line has 13 instants in the first part and 11 instants in the second. The first and third quarters of a doha have 13 instants, which must parse as 6-4-3.

- 2. Two tracks from this album, «Mean Mr. Mustard» and «Maxwell’s Silver Hammer», were written in Rishikesh in 1968.

List of References

This photo series is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Delhi», curated and edited by Suvani Suri.

Project Assistance: Geetanjali Kalta

Graphics/Visual Design: Upendra Vaddadi, Neelansh Mittra

Audio Production: Abhishek Mathur

Video Production: Ammar

Biography

Shop

Published on September 29, 2023

Last updated on November 02, 2023

Special

Snap