In the digital era we perceive modular synthesizers as elusive chimeras of a pre-networked, authentic past. The legendary «Donaueschinger Musiktage» offer in its 2018 edition a different perspective. In the commissioned pieces, the composers Marcus Schmickler and Florian Hecker take the sounds from the past to the now.

The «unearthing» of technology that was once considered cutting edge, and later obsolete, is gaining new momentum. In the electronic music world this has taken on an almost esoteric dimension: old analogue and modular synthesizers are seen as more authentic or pure. They have become elusive chimeras, objects of reverence and desire. Simultaneously, a strange psychological projection is at work: we consider the digital sound as more fickle and untrustworthy than the analogue one, even though the digital sound is more precise and more detailed. On the contrary, the digital makes us even more aware of the old hardware: its presence a form of survival, its absence a form of loss. We are captivated by the sheer existence of a physical object that was built to last, and can therefore be revitalized. Especially in the current era, when most of the physical objects we interact with are unstable and ever-changing, made to break, and made to be replaced. These machines embody the condition of how technology coordinates with our lives. Working with analogue hardware today is not only a form of «pilgrimage», it is also an opportunity to escape into a realm of a non-connected world, where singular objects alone can produce amazing and structured sound. For the musician Robert Lippok, who recently had a residency at the Electronic Music Studio at Radio Belgrade, the use of the revitalized EMS Synthesizer 100 was a «monastic experience», through which our networked reality of clouds of metadata was suspended. This raises the question of a different experience of time and (work) space.

Machines Start Talking

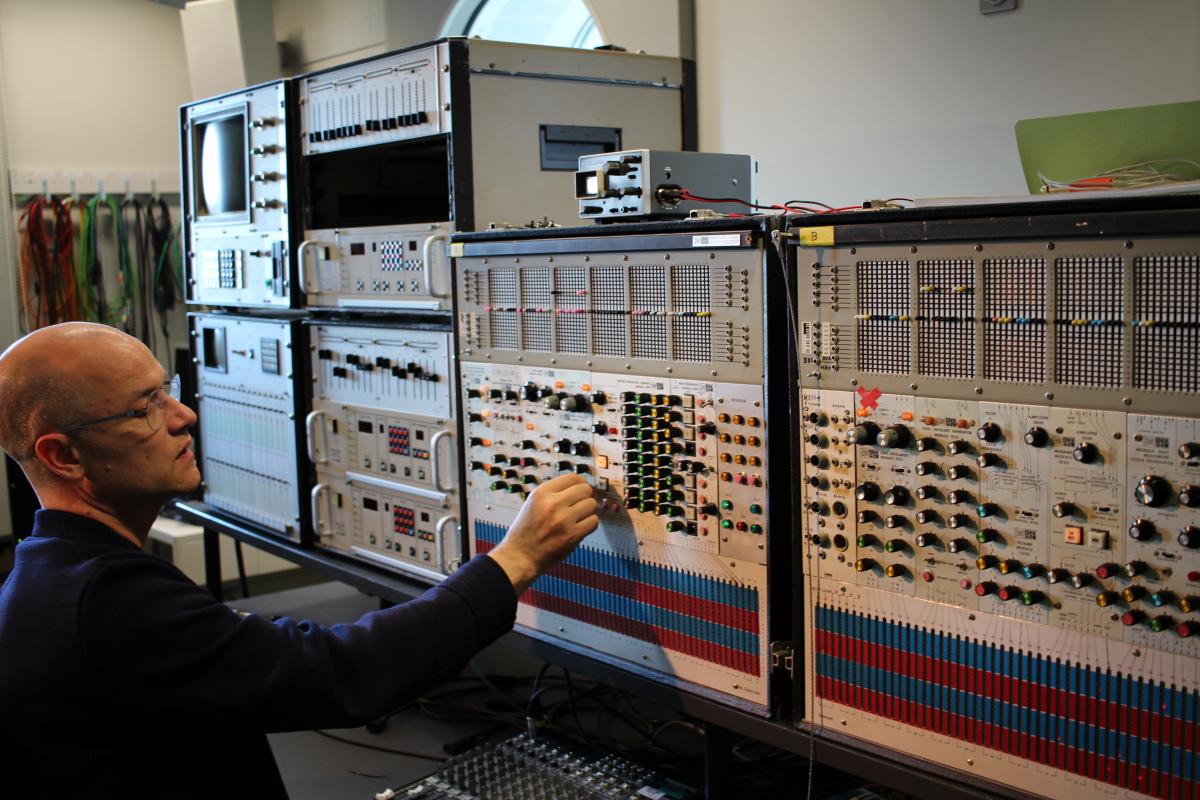

For the 2018 edition of the Donaueschinger Musiktage, the SWR Experimentalmusik Studio Freiburg, one of the pivotal European insitutions of electroacoustic music, offered an interesting perspective on this trend. Many important works of electronic music were created there. On October 20th they have showcased two commissioned works by Florian Hecker and Marcus Schmickler, along with a new work by Enno Poppe as a tribute to the legendary studio. These works, according to the program, will «let famous Freiburg machines speak for themselves». The studio would sound itself in the alignment with current aesthetic ideals of electroacoustic sound. Both Schmickler and Hecker are respected sound artists and composers who combine their knowledge of electroacoustic music with an in-depth theoretical approach and detailed conceptual framework. For his piece «Neues Werk für Elektronik» Florian Hecker uses a «Frei Systemtechnik Filterbank», a digital vocoder, and a filter bank to frame the instrumentation as the central protagonist on stage. The first production stage involved working with above mentioned devices in Freiburg, while the second combined this input with «contemporary models of analysis, abstraction, description and further resynthesis of algorithmically generated sound». In other words, Hecker decomposed the past.

New Sound Politics

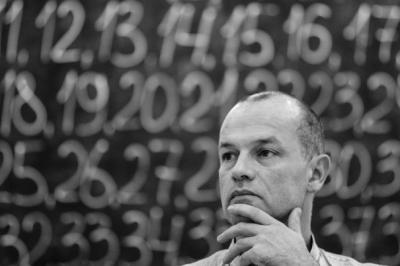

As Marcus Schmickler told Norient in his piece «Sky Dice / Mapping the Studio für Computer und ARP Synthesizer», the studio serves as an acoustic model as well as a model for the sonic representation of historical connections between hardware. In the short span of the piece he uses impulse responses of the empty studio as an acoustic fingerprint. There is a no-input feedback loop which make devices «produce sound by being fed into each other without an external signal». It allows for «the hardware to project on itself without composing an input, without my subjective projection onto the hardware. It sings on its own», Schmickler said. The third level of «mapping» was made by «a sonification of a few circuit-diagrams and some other relevant data produced in the history of the studio». This model raises several questions: Should historical hardware be untouched? Do we have to be reverent or does every musical instrument need eager ears to make it sound and sing? As the philosopher Alfred Sohn-Rethel writes in his 1920 text «The Ideal of the Broken Down: On the Neapolitan Approach to Things Technical», a musician takes control of the machines not only by «studying the manuals or learning how to use them, but by discovering his own body inside the machine». Sometimes machines need to break down so that we can fix them, and this process of incorporation could be a gateway for a new politics of sounds to emerge: one that would understand that harvesting data or having technical expertise is as important as the time spent between man and machine, such as in the historical studio of old. The concerts of Florian Hecker and Marcus Schmickler at Donaueschinger Musiktage promise this. By maintaining the historic machines, they create music that is highly contemporary while not rejecting the technological qualities of a non-connected, pre-networked time.