Taking cues from his interdisciplinary and research-based project Turbo Sud, visual artist and music producer Agostino Quaranta unearths the almost forgotten memories of electronic experiments made with pizzica pizzica, in the Southeast of Italy. In doing so, he questions the place of traditional folk music from the South of Italy within the current cultural landscape of the Peninsula, and opens up a place for debate on the possibilities of its modern re-enactments.

What is it really all about when we discuss the rhythmic and sonic history of South Italy? And what about its electronic counterpart? The music tradition of South Italy usually refers to dances and sound styles categorized under the umbrella of Tarantella. Nowadays mostly associated with folklore or revival enactments, these regional repertoires of rhythmic and melodic patterns only sporadically overlapped with the realm of electronic music. The micro-history of experiments is therefore devoid of much documentation and is often restricted to a number of very few and isolated songs which may be forgotten or slighted even by the people who produced them. According to my personal experience, there is only one historical instance of this musical overlap: the experiments informally coined tecnopizzica, techno-pizzica, or elettro-pizzica.

The Forgotten Story of Tecnopizzica

These experiments appeared between the 1990s and early 2000s in Salento, in a period when the rise of the Folk renaissance was accompanied by the spread of groups producing techno, hip hop, reggae, drum and bass, jungle, and dub music. Some of the aforementioned sounds were likely sung in dialect, creating circumstances where they could co-exist with folk performances, sometimes influencing each other, or even being blended together. Two main references of this puzzling climate were the French anthropologist Georges Lapassade and the Apulian sociologist Piero Fumarola. They researched and actively worked together for several years in bridging possible connections between the local rise of dancehall, club culture, raves, the recreational use of drugs, and the proximity of these themes to the rural traditions of Tarantism. Somehow they likely were even the ones who orchestrated the whole foundation of tecnopizzica.

One of the earliest and most interesting experiments with the use of traditional rhythms is a rare track titled «Transpizzica» (1995) by Pierpaolo De Giorgi e i Tamburellisti di Torre Paduli and arranged by Gino Ingrosso. The song (unfortunately it is not online) is a milestone, combining local drumming with a celestial synth pad reminiscent of the Tangerine Dream era. Just a few years later, in 1998, the album Elettrocontaminazioni Meridiane by Cesare Dell’Anna, Daniele Durante, and Andrea Sammartino was released thanks to the contribution of the cornerstone of Salento’s rural music, Uccio Aloisi, and the high-sounding name of the contemporary revival scene, Antonio Castrignanò. This is interesting to bear in mind since the mixture of technological and traditional elements was not that well-received by the Salento mainstream audience of folk music, as I have noticed talking both with fans and artists. Another band that sometimes embraced the technological conversation around pizzica’s rhythmic heritage is Nidi D’Arac, a group founded in Rome in 1995 by the musician Alessandro Coppola. «Nella Rete» (2001) is definitely the most glaring example of a cyberpunk pizzica pizzica made by the group.

Intellectual Utopia or Isolated Events?

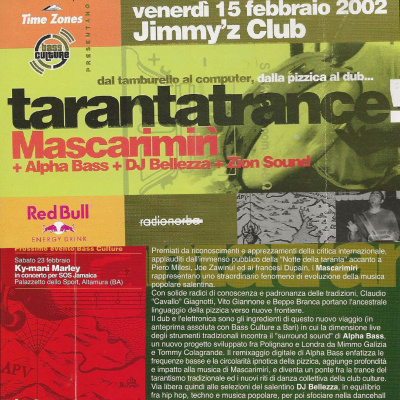

Between 1997 and 1998, experiments by different artists, including the internationally renowned group Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino, were performed live in squatted social centers around Italy. Other public demonstrations were made on some occasions by the Reggae collective Sud Sound System, singing in dialect side by side with some tambourine players. Otherwise, in 1999 a live version of tecnopizzica was even broadcast on the Italian commercial pay TV channel, TELE+. Following this timeline of now-forgotten events, the last live performance of tecnopizzica I could trace was organized in Bari at Jimmy’z club, in 2002, in collaboration with Red Bull.

The main themes of that night, as reported on the flyer, were music performances ranging «from the tambourine to computers, from pizzica to dub» by Mascarimirì, Alpha Bass, DJ Bellezza, and others. The event was lined up from a collaboration consolidated by Mascarimirì with Alpha Bass for the release of the album Taranta Trance in 2000; the album contains an awesome track titled «Trancedelic», which is probably one of my favorite tracks ever made within this context. The third guest of that gig, Dj Bellezza, is a deejay and music producer who produced two very beautiful unreleased experiments with tecnopizzica in 2003. In parallel with his music production, Bellezza has been busying himself for the past eight years with the construction of two DIY MIDI-triggered frame-drum tambourines.

Despite the presence of various examples of great electronic music tracks sampling the frame drums of pizzica pizzica, the majority of the musicians who made them never threw themselves headlong into these experimentations in a systematic way. Consequently, the name tecnopizzica and the concept of these experiments is still unknown even in Salento, the area where this sound should theoretically belong. But why? This is probably due to the absence of platforms, such as club nights or record labels fully invested in introducing a club music and technology-oriented narrative within the discourse of pizzica salentina. However, I believe that the reason can also be found in the academic discourses around so-called «neo-tarantism» prompted by Fumarola, Lapassade, and other intellectuals.

There are indeed many questions about this topic that are not easily answerable. For instance, despite the popularity of the revival, was the 1990s youth of Salento still maintaining a spontaneous and vivid link with the rural musical traditions and rites famously documented by Ernesto De Martino and Alan Lomax? If not, was the revival in Puglia heavily driven both by the new age trends and the intellectual and anthropological re-considerations of the phenomena? And what about tecnopizzica? Will it ever be revived? Or will it just remain an eccentric academic utopia and a quickly left-behind chapter of folk music from the Southeast of Italy?

Politics of the Folk Revival

«Will taranta ever reincarnate in something current and at the same time faithful to its history, thus expanding its catchment area, or is it destined to remain confined to the niche created by and for the taranta lovers themselves?». In 2016, this interesting question concludes an article by Sonia Garcia on Vice Italia (Garcia 2016). Her piece asked vital questions about authorship, authenticity, and identity concerning the contemporary Italian music industry. Furthermore, it was the first article in recent times to question the potential of the South Italian music traditions in the field of electronic music.

According to Garcia, Italian pop music has very little to do with the local musical ecosystem that has historically characterized the entire peninsula. Her interpretation of the current Italian music scene harkens back to Anglo-American influences, which she considers a result of standardized and profit-making market dynamics. On the other hand, the writer suggests that some traditions like pizzica pizzica (often mistakenly called taranta) from Salento may be powerful grounds for experimental and unprecedented tendencies in the branches of Italian electronic music, specially considering the problems related to many Italian producers who «rather have a much greater interest for exotic sounds such as African, Asian or South American rhythms» (ibid.).

The discourses around the music traditions of the whole Italian peninsula are often a byproduct of the cultural and political climate of the 1970s through the 1990s. This period can be seen as an experimental ground as well as a crucial moment for opening up a conversation about South Italian local identities, usually subject to stigmatization and backwardness. It created chances to give birth to some prolific and independent music scenes, while also contributing to develop regional cultural industries in areas which were hit by structural socio-economic issues.

However, the political philosopher Francescomaria Tedesco would argue that the revival movements, singling out that of pizzica salentina, have been driven by intellectual classes who most of the time ended up portraying Southern Italy through the lense of «Mediterraneism». Tedesco considers the latter as a performative cultural and political trend / ideology based on processes of self-orientalization, which prompts the simplistic and exotified idea of a sea and its enclosing territory as an atemporal and archaic Mediterranean land, crossroad of people, as well as gateway to the «Orient».

I would personally consider it wrong to put the whole mosaic of Southern Italian folklore, traditions, and their derivatives, under this blanket. However, I still believe that the perspective evidenced by Tedesco plays a crucial role in the way folklore was collectively reimagined in the last fifty years. One example is the criticism he makes about the heavy interdependence between «intellectual» folk music circles and ethnomusicologist practices. This dynamic effectively risks boxing folk music into an anthropological experiment, or creating bands which are mostly led by the intention of re-enacting ethnomusicologist research under the guise of «tradition».

Secondly, according to Camilla Hawthorn, who researched the concept of the Black Mediterranean, the widespread Italian academic rhetorics about the intercultural identity of the sea (the tendency that Tedesco similarly observes in some folk revival circles), even if driven by good intentions, can risk minimizing the dramatic militarization, border surveillance, racial violence, and the complications of contemporary diaspora ethics in Italy.

The whole idea of folklore in Italy, including the South Italian one, has often been inscribed in the slippery labels of «world» and «ethnic music», an outdated container which should undoubtedly be challenged due to its rooted ties to the notion of the «exotic» (Kalia 2019). This is probably why, even in the realm of folk music scenes, not unlike the mainstream Italian music industry, there is still the need to confront some issues of cultural appropriation (or improbable «contaminations» with traditional sounds from other parts of the world).