«I’ve Never Considered Myself a Futurist»

The musician Ata Ebtekar, aka Sote, is helping to build an experimental music scene from Iran and Iranians abroad: contemporary music that engages with tropes of the past. On the occasion of his performance «Parallel Persia» at the music festival «Donaueschinger Musiktage», which is dedicated to adventurous music since its founding in 1921, Norient asked how much this music might tell about the future.

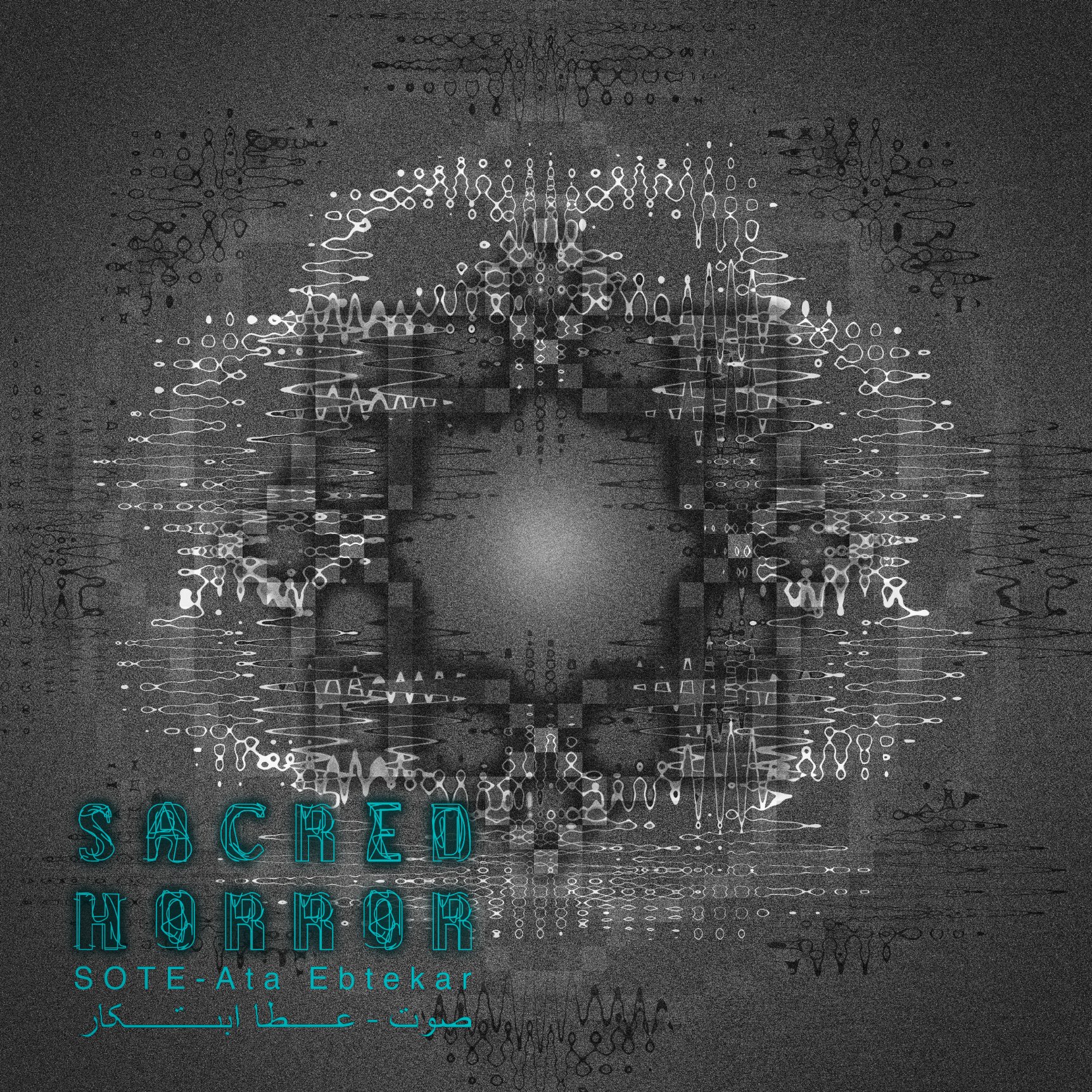

Born to Iranian parents and raised in Germany and the U.S., Ata Ebtekar spent most of his life outside of Iran before taking an interest in Persian music and releasing the compilation Persian Electronic Music 1966–2006. This year his label «Zabte Sote» released four albums by fellow Iranian producers from Tehran and abroad, featuring instrumental electronic music that has found a niche for itself within the complex cultural landscape of Iran.

Just like Ebtekar with his own music, Rojin Sharafi, Ixual, and Temp-Illusion are operating widely without beat structures, but rather with a flow of sounds and textures that draws from Iran’s musical history, utilizing microtonality and classical instruments, tunings, scales, and rhythms, which have been densely processed and blended with a wide range of synthetic sounds. The most bladerunnered1 soundscapes come from Nima Aghiani’s album Convergence Zone. It has the track titles to match: «Automaton», «Humachine», and, even more ambiguous: «Submit/Defy». The album is «about that moment of impact, of clash, of mergence; the acceptance or the rejection of instruments, machines and devices as an expansion to one's body».

Even though the composer is based in Paris, it is tempting to listen to the album as a prototype for musical science-fiction from Iran. As a narrative genre, sci-fi plays such a marginal role in Iranian mainstream culture that it has to share space with its sister-genre fantasy, both subsumed under SFF. However, writer Mina Talebli reports that with the success of the «Harry Potter»-Series and the ongoing popularity of Ursula K. Le Guin, SFF literature is maturing from its earlier reputation as a «white men» thing. According to an article by Somayeh Karami, the number of original works by Iranian authors is still small, but growing.

Acidentally Futurist?

As Ebtekar almost accidentally started his career with a one-off release on the futurist label Warp, he is a good source to ask about the role of science-fiction and futurism within the small experimental music scene in Tehran. But in his return email he hesitates to take up the thread. «I’ve never considered myself a futurist», he answers, probably thinking of Marinetti and the Italian movement more than of Autechre and Aphex Twin, «as futurism comes with a set of rules and concepts that I find limiting. As an example, I’ve always respected culture and folklore. I think that it’s essential to know tradition, and when it comes in a healthy dosage, it can be very valuable. Rejection of history is arrogant and pretentious.»

His research in classical modes and their synthetic deconstruction might rule out any notion of futurism, and definitely provides enough material to keep him busy and grounded in the present, as well as the re-constructed past. In this way he contributes to the historical turn in music that Simon Reynolds portrayed in his book, Retromania. Ebtekar recounts:

In the early 2000’s I started to investigate electronic music composition without conventional beats. At the same time, I was listening to [a] considerable amount of Iranian classical music, which by the way, can come from lots of purist aesthetics. I felt it was time to deconstruct this beautiful tradition and create my own reality of what Iranian music could be in the present time or possibly the future. All these concepts are just about having fun with ideas. The important thing is the outcome of the music composition and the experience of listening to something new within an electronic music framework. The beauty of sound synthesis in music composition is vital.

Sound Is Central

Apparently careful not to fuel exaggerated expectations, Ebtekar plays down the role of specific narratives or intentions, and rather emphasizes the sheer sonic aspects of his work. But he admits that «Iranians are going through some very difficult times at the moment. They have actually been going through lots of ups and downs in the past few decades. It’s only logical for experimental artists to play with dystopia and utopia in various shapes and forms».

While in Western mainstream culture the most optimistic futurism has made way for future angst, science-fiction simultaneously remains a source of ideas for blockbuster movies. Nevertheless, it is still an attractive option for regarding the present from a future angle. With long literary and musical traditions that constantly transform to match with the present, and young Iranians’ undeniable desire to synchronize with global cultural trends, it will be interesting to observe what Iranian artists create. For this, «Zabte Sote» seems to provide a viable channel.

- 1. That’s an actual word! Coined by William Gibson in one of his recent novels.

Norient is media partner of Donaueschinger Musiktage 2019.

Biography

Links

Published on November 14, 2019

Last updated on May 18, 2021

Topics

Snap