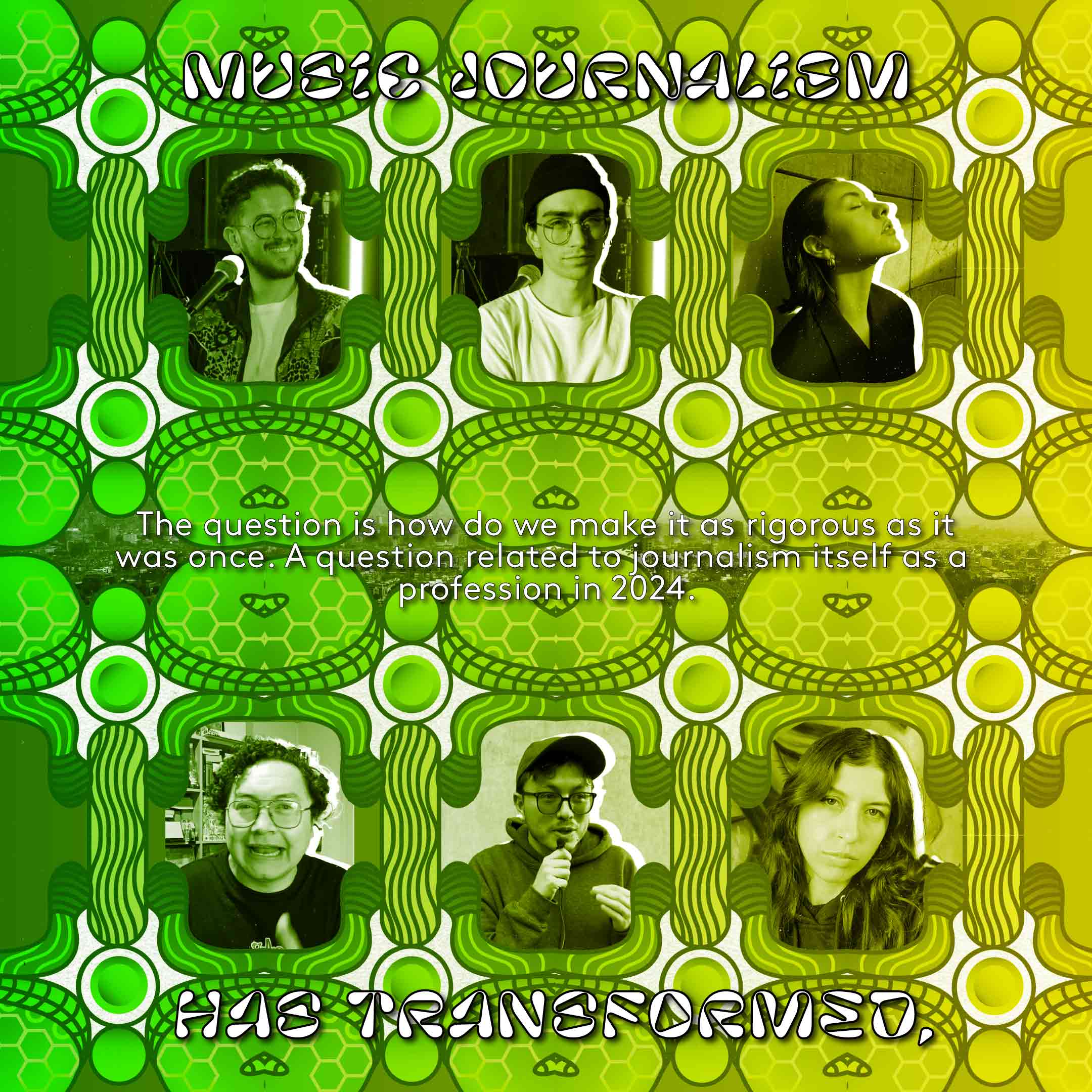

Bogotá’s Music Journalism: An Era of Reconstruction

With platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube blurring the line between journalists and content creators, some communicators adapt to fast-paced digital dynamics, while others uphold long-form reporting. Bogotá’s music journalism, once thriving, now faces a gap due to a lack of specialized journalists. This void allows content creators to reach new audiences with innovative coverage, but without the rigor of traditional media outlets.

encuentre una versión en español de este texto aquí

In Bogotá, as in many other parts of the world, music journalism is in crisis. Long before the waves of layoffs in key media outlets in the global North such as Bandcamp or Pitchfork, Bogotá-based media outlets that were leading the way in the independent music scene during the 2010’s, like Revista Metrónomo, Cartel Urbano, the local franchise of VICE, and Revista Arcadia, had already closed or were operating irregularly with a reduced editorial staff. This harsh reality led music journalists to distance themselves from the profession or seek new ways to practice, considering the limited space in traditional media for music journalism in Colombia.

Although these closures are due to various factors, they are mainly attributed to a lack of funding and have been ongoing since at least 2016, when Revista Metrónomo stopped publishing, leaving a gap in coverage that was once a reference point during the days when the Bogotá alternative scene was finding new ground. This was thanks to the work of independent collectives like Noise Noise and Discos La Modelo, the emergence of a new wave of artists including N. Hardem, Nicolás y los Fumadores, or Las Yumbeñas, and the rise of Páramo Presenta, the production company behind the Festival Estéreo Picnic – the Colombian version of Lollapalooza – which brought artists like The Strokes, Gorillaz, or Tame Impala to the country for the first time.

Bogota’s Music Journalism in the TikTok Era

One of the journalists who has strived to find a place amidst the crisis is Sebastián Narváez, former editor of Noisey, the music-focused media outlet of the now-defunct VICE magazine that was based in Bogotá until its closure in 2019. Fearing a lack of opportunities in established media and with a significant name in the local music scene behind him, Narváez founded Sudakas, a podcast featuring in-depth interviews with various South American artists. «People are increasingly less likely to visit and read content on media outlets, and social media has become the main platform to access information. So, it becomes an exercise in adaptation, betraying tradition a bit, and creating formats that respond to what our generation is consuming and the platforms they use», says Narváez.

With Sudakas, Narváez won the prestigious Simón Bolívar National Journalism Award in 2020, an achievement that felt like a collective victory for a group of music journalists hit by the crisis and often ignored in these awards. The prize money would also be the starting point from which Narváez tried to make the project economically sustainable. Other strategies have been to open a Patreon1, sell merchandise, collaborate on projects with social organizations, or work with brands like Jägermeister, which funded one of the seasons of Sudakas. However, it has still not been enough to be able to live off the project.

Also focusing on social media, though not necessarily through the lens of journalism, other platforms based entirely on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube have emerged in recent years focused solely on music creation. The most recognized and possibly the leading figure in the city is El Enemigo, a key platform for the promotion of local music that has been operating since 2014.

«I deeply regret the lack of traditional music media, especially because as a profession, there are reflections that need to be made through newsrooms. I do believe that it is also true that there is a misunderstanding that the world of social media implies certain advantages, conditions to which we have to adapt rather than simply rejecting», says Juan Diego Barrera, part of El Enemigo and a journalist who has worked on short formats mainly designed for TikTok.

This channel has transcended the local album reviews with which it made a name for itself, and today it covers festivals, opens discussions about the local scene, and profiles independent artists who are left out of the radar of entertainment journalism, which is more guided by the number of plays on Spotify and the work of press agencies. At this moment, El Enemigo’s main source of income is sponsored content with brands that advertise on their content. It is important to note that TikTok still does not allow monetization with content in Colombia, which for Barrera is one of the major barriers to sustaining their work on social media. «Achieving the economic sustainability of having a team of four people hired with a decent salary is still a long way off», he says.

At this point, it is important to mention the projects of Sara Sofía Rojas, a journalist and content creator who is the face of Suena Suena – a media outlet dedicated to telling short stories about Latin music on Instagram – and, where she showcases her work as a DJ and tells stories about that musical genre on the same social network. «I used to write about music in a general way, but when I started working on TikTok, I decided to focus on salsa, and that’s how I was able to reach a niche with which I have been able to grow», says Sara Sofía.

In the past, she was hired in the culture section of Publimetro, a traditional media outlet where she experienced the pressure of producing eight notes a day. «Now I am my own editor, so I talk about what I feel like and not what I don’t feel like, which would turn out very badly anyway». Suena Suena’s financing goal is to have content sponsored by major record labels, creating in-depth content with some of their artists. Until the completion of this report, only Warner Music had contacted them, and it was for one specific video. Meanwhile, the rest of Sara Sofía’s work within this platform, which already has 65K+ followers between TikTok and Instagram, remains unpaid.

Other new references in this ecosystem are Álvaro Villa’s Cadencia Podcast and Nicolás Rodríguez’s El Caído Reviews. Anyone who goes to shows of independent bands in Bogotá or closely follows any of these artists has surely seen Álvaro’s or Nicolás’s faces on TikToks or Instagram reels. Neither is a professional journalist, and with content based on reviews, interviews, and concert recommendations, they have turned their platforms into important megaphones for the dissemination of the Bogotá scene.

«The constant reduction in the attention spans of people consuming increasingly shorter videos or resisting reading moderately ‹long› texts has put many of the more classic formats of written journalism in crisis», says Álvaro about the reason why some audiences may be turning to the Cadencia Podcast. Nicolás has a similar opinion and is emphatic in saying that in his search to find a formula that would make his content go viral, he discovered that the quick format of platforms like TikTok was becoming the ideal medium to talk about independent music. For both, there is already validation from the audiences, although there are still sectors within the music industry that do not consider them as media.

Another issue they both face, similarly to the other projects previously mentioned, is the difficulty in financing themselves. As media outlets that remain active in the cultural agenda, both Cadencia and El Caído Reviews sell customized advertising for concerts in the independent scene. «There are some bands that want to buy a review or a positive comment about their work», says Álvaro, who prefers to remain true to his audience rather than sell a positive opinion for a few pesos. Nicolás stays within the same ethical line but says that selling advertising for 150,000 pesos per event is not enough money to be sustainable. «We are doomed», he says with a laugh.

«Concerts Insiders»: The New Darlings of Audiences and Showbiz

This discussion about what is and what is not a media outlet could also be extended to the universe of concert «insiders»: X profiles like @Juanjo_guerrero, @Miguel_G_1_1, @Pogotaconcerts, and the most recognized, @musictrendscol, which appeared in 2017 and today is reaching the numbers of X followers of Shock, probably Colombia’s longest-running music-focused media outlet. This recent phenomenon is based on attracting audiences by providing scoops on mega-concerts, which production companies like Ocesa, Páramo Presenta, or TBL Live turn to in order to increase excitement around their announcements and amplify the communication of the concerts they are selling. There is no certainty about the economic deals between production companies and these types of platforms, although they have been questioned for acting as mere channels of promotion.

Although several music journalists, including the author of this piece, have criticized the way MUSICTRENDS attracts audiences based on rumors they hear or see on the internet, the most infamous moment came in July 2023 when Primavera Sound Bogotá, in its first edition, announced that specific platform as a media partner. As a quick note: MUSICTRENDS is the largest concert promotion platform in Colombia, and with the post-pandemic reactivation, it has become the go-to source for audiences to stay updated on the live show scene.

This alliance with Primavera Sound was purely based on audience metrics and ultimately did not work out, as the festival was rescheduled in the form of two smaller arena dates that kept only a small part of the lineup amid criticism for the poor use of its communication channels. Narváez explains this phenomenon by saying that «after the closure of specialized music and culture media outlets, many initiatives by music enthusiasts have emerged that do not have the knowledge and rigor that journalism brings to certain topics. Pages like that are based on information that has not been verified or is based on speculation».

Along the same lines is Nathalia Guerrero, who was part of the editorial team of THUMP Colombia, the electronic music-focused media outlet of the now-defunct VICE. Nathalia is one of those who have abandoned this side of the profession after the closure of some specialized newsrooms and in search of better job opportunities within journalism. For her, music journalism has always been a crisis within the general crisis of journalism, which is based on labor precariousness and the lack of spaces to practice. She emphasizes that this lack of spaces is not completely covered by the work of projects based on social media:

«The lack of spaces has been supplanted by content creators and social media platforms that, although they act as cultural journalism, cannot be completely called that. There are blogs, reviews, vox populi at events, and for me, that is part of the ecosystem of native content about music, but it is not the same as journalism. In this era, all content is designed to be digestible and to comply with short digital consumption, which is eroding research, one of the foundations of cultural journalism. The saddest part is that the few music journalism platforms that remain are embracing this trend in search of more traffic.»

Content Creators in the Media Realm

One of these platforms is Shock, founded in 1995 within the Caracol Medios conglomerate, which has had to transition from print to digital and more recently to the realm of social media. Today, they present most of their work via TikTok and Instagram reels, which is why, in addition to journalists, they have expanded their network of contributors to influencers and content creators. According to David Chaka, the editor-in-chief, this decision led to over seven million views for their video content last year in some specific months. It is a natural need to reach new audiences where «perhaps massiveness, for us, consists of a formula that combines music journalism with entertainment».

For Santiago Cembrano, one of the most respected music journalists in Colombia (and an author of this publication as well – read his article on the evolution of hip hop in Bogotá), the problem of journalism falling into the hands of content creators has to do with immediacy and the end of some classic journalistic formats. «When the same media decide that the audience no longer wants long-form works because we can only think in terms of TikTok, they may be wasting the potential of journalists who have to start thinking about their work in that format», says Cembrano, who is also the author of three books on rap and logically declares himself against short formats as the only way to represent journalistic work.

What Once Was

One of the bastions of these investigative and extensive journalistic formats was Revista ARCADIA, a reference point in the profession that was reduced to a section of its main branch, Revista Semana, after bankers bought the brand in 2020. Beyond just focusing on artistic creation, ARCADIA was a reference in opening discussions related to government policies that directly affected art, and was especially critical of the «Economía Naranja», a concept of cultural marketing championed by Iván Duque, the right-wing politician who was president of Colombia between 2018 and 2022. Since then, the void left by that publication, which also served as a space where much of Colombian cultural journalism converged and asked questions, has not been filled. Felipe Sánchez, former web editor of ARCADIA, comments on what has been lost:

«Journalists and media outlets that have sought to continue that path, to resume the questions and discussions that were sustained there, constantly clash with the effects of that dispersion and atomization: fewer readers, less debate, disconnection between sector agents, difficulty in posing difficult questions, economic precariousness. The light that some feel thanks to the new map of independent journalists, content creators, bloggers, YouTubers, and independent TikTokers who want to cover the cultural sector in other ways is not enough. Without a center to organize around, without a common space like ARCADIA was for years, many run the risk of fading, repeating themselves, or not being able to move the conversation out of their niches.»

Inside Bogota’s Journalism Trade

Under Colombian law, journalism is not considered a profession but a trade. This means that it is not a requirement to have a university degree to practice. However, according to data from the National Higher Education Information System (SNIES), there were 26,000 students enrolled in the Communication Studies program in the country last year. The majority of these students are enrolled in universities with high-quality certificates such as Universidad Javeriana, Universidad Externado, and Universidad del Rosario, all located in Bogotá. Of these, only Universidad Javeriana offers a diploma in Journalism and Cultural Criticism. In Bogotá, cultural journalists are not trained in academia but in newsrooms, and as we have mentioned throughout this report, these are becoming increasingly scarce or do not have culture as a main focus.

For now, music journalism in Bogotá is still going, but still far from the power it once had. Beyond whether they meet the expectations of what many expect from cultural journalism, projects like Sudakas, SuenaSuena, El Enemigo, Cadencia Podcast, or El Caído Reviews do a thorough job of covering the music scene in the city. It is also a fact that they are far from being economically stable, operating more with heart than with pocket. Meanwhile, Shock and other traditional media outlets that publish about culture and have a financial base to operate, are therefore betting on social media dynamics to renew themselves and reach new audiences. In the process, they have relegated journalistic formats that in a way give legitimacy to this part of the trade, often overlooked amid the major discussions that take place in the media about politics or economy.

Music journalism has transformed, the question is how do we make it both as rigorous as it once was and also equipped with decent salaries, another long standing problem – a question related to journalism itself as a profession in 2024.

- 1. Patreon is a membership platform that allows creators to receive funding directly from their fans or patrons. By subscribing, patrons can access exclusive content, rewards, and experiences offered by the creators they support, helping artists, musicians, writers, and other creators to sustain their work financially.

This essay is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Bogotá», curated and edited by Luisa Uribe.

Biography

Eduardo Santos is a social media manager and cultural journalist. He has written for media outlets such as Cerosetenta, Noisey Colombia, Revista Arcadia, VICE, and Shock. He is the co-author of the book Nuevo Pop Chileno: el sonido de una generación en llamas and the bassist for the band Yo No La Tengo. Follow him on X or Instagram.

Published on August 22, 2024

Last updated on January 15, 2025

Topics

On new cultural implications of Meme Music, and how commnunication is more and more a result of power relations disguised in social networks.

What is conveyed or represented by a particular arrangement or sequence of things.

Special

Snap