Colonialism is not over, it’s just less visible, especially in culture. As a curator of the Berlin-based label Global Pop First Wave focussing on non-Western pop music, Holger Lund sees himself entangled in neo- or post-colonial paradoxes. An essay about the dialectics of westernized local and global pop music and why its decolonization is inevitable.

«When you are decolonized, colonialism is not simply taken away from you. The essential subject of decolonization is a critical view on colonial patterns of thinking, colonial categories, colonial history of knowledge [...].» (Rassool 2017, 150, translation: H.L.)

«As a matter of fact we have a problem with our history and our memory, since these have been written by the conquerors and not by the colonized people. Generations of Cameroonians were told that their ancestors had been the Gauls, although that is completely wrong.» (Obolo 2017, 179, translation: H.L.)

Points of Departure

In this text I want to take a look at some of the mechanisms for constructing global pop music history and to question them from a decolonial point of view. To achieve this, I will examine some examples and case studies, specifically in regard to Turkish and Brazilian pop music history. There are two points of departure for the following notes on decolonizing pop music and rewriting global pop music history: one is my work with the vinyl record label Global Pop First Wave, the other the observation that colonialism is not over yet. Global Pop First Wave is a sublabel of Berlin-based Corvo Records. While Corvo Records publishes contemporary experimental music, Global Pop First Wave has a focus on music archeology with re-releases of historical non-Western, especially Turkish pop music.

To produce the re-releases, which are dealing with the so-called first wave of global pop music in the 1960s and 1970s in the form of compilations, I work with a worldwide network of record sellers, connoisseurs, and scholars. In addition, I am conducting research internationally in record shops and private archives as well as using databases on the internet. To produce the compilations, the original vinyl records have to be tracked down, retrieving information from the records sleeves and record labels, which often give important first hints about the music and its production. Then the original records are digitized, restored, and newly mastered in a mastering studio in Berlin, before being cut, again on analog vinyl, to be sent to a pressing plant.

As a curator, I try to give access to music that has been neglected, overlooked, or peripheralized, and my efforts are therefore part of an attempt to rewrite and redefine the canon of pop music. Depending on your perspective, the notion that colonialism is not over yet can be based either on a conviction that colonialism has never ended, or on the analysis of a neo- or para-colonial push observable today (Mbembe 2015, 229 and 244–245). Of course, it also depends on what we mean by the term colonialism. If we think of land grabbing, then we will find that there is indeed a process of massive land grabbing as a form of neo-colonization going on in Africa, escorted by armed police forces and initiated by multi-national agriculture organizations.

This process is described in the two documentaries Bauer unser (Robert Schabus, Germany 2017) and Dead Donkeys Fear No Hyenas (Joakim Demmer, Germany 2017). In the documentary The Revolution Won’t Be Televised (Rama Thiaw, Senegal 2016) we are told about the EU using corrupt African governments, installed with the aid of the Western world, to buy fishing licenses for the west coast of Africa, especially for the Senegalese waters. The EU is then selling these licenses to multi-national fishing companies, thus threatening the existence of thousands of local fishermen. Many of these people, cut from their means of subsistence, are turning into refugees, which are exploited as cheap labor forces in Europe. The film shows how this licensing policy produces the refugees.

The Politics of Entanglement

However, we can find the problem of (neo-)colonialism almost everywhere. For instance, if we have a look into the kitchen of the restaurant in the House of the World’s Cultures (HKW) in Berlin, an institution officially supporting a very critical discourse on colonialism, we will find the classic first-to third-world hierarchy: a white male director is in charge of the whole institution, a restaurateur of Turkish descent runs the restaurant, and many low-paid kitchen assistants of African descent are doing the dirty work. It seems to me that colonial structures are even more powerful here than the – thoroughly serious – dedication to a critical discourse on colonialism. What is the reason for this? Why does the critical discourse seem to have less power than conventional colonial structures in its own home of anti-colonial thinking? And how does that relate to my own work for the label Global Pop First Wave? I feel entangled in neo- or post-colonial paradoxes as well when it comes to Global Pop First Wave.

The concern to decolonize pop music – meant as a detachment from colonial structures of power, thought, and judgment relating to pop music – is pushed forward mainly by writers in the U.S. and Europe, where the crucial centers of power and decision-making are located, even for the post- and decolonial discourse. For an example, let us look at Peruvian psychedelic music of the 1970s. Only after the Brooklyn-based label Barbès Records had begun to re-release several records from this genre in 2004, Peruvians in Peru started appreciating their own psychedelic music of the past, according to the motto: if the Brooklyn hipster tags this music as cool and re-releases it, it really has to be cool. Hence this kind of music is now played again at parties and clubs in Peru by Peruvians. The defining fact is that the archeological workup and revaluation of the genre is passing through Brooklyn hipsterism.

For Turkish pop music of the 1960s and 1970s, the procedure is about the same. From the «Californian Stones Throw podcast #12, Turkish Funk Mix» (2006), up to the compilation series Saz Beat Vols. 1–3 (2013–2017) on Global Pop First Wave, as well as the frisky use of Turkish samples for hip hop beats in the U.S. (Oh No, Dr. No’s Oxperiment 2007) or in Sweden (Rikard Skizz Bizzi, Ur Funktion 2, 2016), Western engagement caused a new wave of admiration for historical Turkish pop music both inside and outside of Türkiye. This admiration also led to the foundation of new Turkish music labels by Turkish people, both inside and outside the country, often doing archeological work such as Volga Coban’s Arşivplak (translates as «archival records»; since 2012) and Ercan Demirel’s Ironhand Records (since 2016). These labels cope with the task of working through and re-archiving Turkish pop music history, which had been deleted by the coup and the following military dictatorship in the 1980s. An important step to do so in the future is the re-establishing of a Turkish pressing plant in Türkiye with Nova in 2019. Similar models of re-archiving are offered by the Nigerian label Odion Livingstone run by the producer and musician Odion Iruoje and dedicated to Nigerian pop music of the 1960s to the 1980s, or the Ugandan label Nyege Nyege Tapes, which focuses on Ugandan pop music both contemporary and historical (Odion Livinstone 2019, Discogs 2019a; Discogs 2019b).

«There’s a Whole World to Discover»

Let us take a deeper look at this process of rediscovery in the case of Brazilian pop music. DJane Mafalda from the label Melodies International recently asked the Brazilian DJ and producer Tahira how he had begun collecting Brazilian pop music. This is what he answered:

I’ve been buying records since the 90s. It’s funny how it all started, as it was actually because of a foreigner. I’ve always been a music fan but I didn’t have much of an affinity with Brazilian music. I was a fan of American music, Jazz, Soul. I didn’t have a connection with Brazilian music because on the radio here they played a lot of Pagode, a very Pop Samba which I didn’t like much and so that was my reference of Brazilian music at the time. In the beginning of the internet, I was part of an Acid Jazz mailing list that was big in Europe, but that here in Brazil no one knew about it. They found out I was Brazilian and someone asked me: «Ah, you’re a Brazilian. I’m a fanatic, I love Brazilian music and I’m looking for some records, I’m a collector. Do you think you could help me find them?» So I agreed: «I don’t know much about it, but I can have a look.» He made a list with 20 titles and I started looking. At the time there wasn’t really a digging culture here like there was in Europe and the U.S., I found a lot of those records and they got me curious. «What does this guy want, what is it?», he had asked for Banda Black Rio, Azymuth, Batudaca, Fantástica, many Jazz, Funk and Soul records.

I looked for these records, found some and I listened to them I was amazed! It was completely different from the Brazilian music I knew from the radio. […] I felt silly about what he showed me. That’s when I thought, «There’s a whole world to discover here.» That’s when I started collecting and searching for Brazilian music. It was from this moment and it was because of a foreigner. […] In the 90s, Brazilian radio wasn’t very good. Brazil was dominated by Rock, there was only national Rock and commercial Samba (Pagode) playing. There was no way for you to know unless you were a researcher, there wasn’t a way of having access […]. Thank god someone from abroad showed me and I followed him […]. [sic!] (Mafalda 2018).

With this quote in mind, we can see the barriers which hindered access to Brazilian pop music history: a restrictive and non-historical radio program as the main means of music distribution, coupled with a lack of historical pop music education. Similar developments can be noticed for Türkiye (military coup, 1980) and Iran (religious and military coup, 1978/79), where the new governments blocked all previously existing pop music. In Brazil, the military dictatorship ended in 1985.

Tahira’s example points to the fact that some real research energy (and the methods to do research) would have been necessary to gain any knowledge. The lack of what he calls «digging culture» is also important. Digging culture is part of a countermovement against the physical vanishing of music during the course of music media history (cd, mp3, streaming). It is connected to Western «retromania», as described by Simon Reynolds (2009), to Western audiophile listening culture, as well as to a Western beat-making culture. In many countries worldwide, non-Western music on vinyl was regarded as worthless and generally outdated.

The turning point for Tahira was the European foreigner he mentions who – ironically – led him to the same styles of music, that is Jazz and Soul music, he favored already. So, the estimation and revaluation of Brazilian music that developed in Tahira – as an example for a Brazilian music lover – was triggered by someone from outside of Brazil belonging to the Western world. Tahira summarizes: «recognition came from outside» (Slater 2018). And Caio Beraldo explains it in a similar way: «[…] gringos have been interested in the ‹B side› of Brazilian music, way before Brazilian people, and you have got to respect that in a way» (ibid.).

A «whole world to discover» – that is how Tahira calls it. And indeed, it still remains a «whole world to discover». Brazil was put on the music-digging map drawn by Western vinyl collectors in around 2000. For about ten years, there has been a continuous stream of re-releases of historical Brazilian pop music on vinyl, first made outside, then inside Brazil. A very important step was made 2016 with the establishing of the pressing plant Vinil Brasil, «a factory made by musicians and music lovers for the use of musicians and music lovers», (ibid.) which allows Brazilians «staking a claim to their own music once again».

The Westernized Approach to Brazilian Music

Even trends are recognizable, such as the Brazilian Disco-Boogie music of the 1980s, which has been re-released continuously for about five years, and predictions for trends can be made, e.g. for Brazilian hip hop of the 1990s. As yet, there are just very few re-releases of the latter, but they will come for sure since the national hip hop scene of the time was totally under the radar globally, with labels like TNT, Kasakata and Zimbabwe, and the dainty and dirty music of formations such as Comando D.M.C., Baseado Nas Ruas, DF Movimento, P.MC Poetas de Rua, Duck Jam e Nação Hio Hop, and Geração Rap, to name but a few. And still the mechanism is the same: already, collectors from outside Brazil are demanding more and more Brazilian hip hop of the 1990s, therefore setting the focus on a genre that the Brazilians themselves still tend to neglect or even regard as irrelevant (especially as a genre related to the favelas). Everything will follow the usual pattern, Western collectors will draw the map and set the agenda for re-releases, the Brazilians will follow, re-thinking and revaluating their own music history and joining in with re-releasing their own historical pop music.

Another example for the effects of a specifically Westernized approach to Brazilian music is given to us by Rodrigo Plaça. He is a young Brazilian record dealer in São Paulo, making a living out of it. What is special about him? He has no physical store of his own, instead he digs in record stores all over the country, from Salvador to Porto Alegre. One of his many working places is the huge Casarão do Vinil in São Paulo (images 1 to 3).

He sells his findings via the internet (e.g. on discogs) to customers in Brazil and all over the world. The specific point is that, according to his own story, he has trained himself to be able to listen to Brazilian music with «Western ears», keeping in mind what Western people would like or search for in Brazilian music. He is doing this so well that his «Western ears» are his business model. At the same time, he is connected to Brazilian DJs and producers like Millos Kaiser, one half of the Brazilian duo Selvagem, who recently published the compilation Onda de Amor (2018) for Soundway Records in London (image 4). Thus, Rodrigo’s work feeds into Kaiser’s work, which is described in a promotional text as follows:

The release also covers a decade that has been intentionally forgotten and brushed aside by many in the country. Onda De Amor is a release that is loaded with smooth grooves, bubbling bass, glistening synthesisers, funk strutting guitar lines and sheen of production that undeniably marks it of its time. For Kaiser this compilation is about reintroducing music during a period of reappraisal, catching a new wave and hoping contemporary listeners will ride it with him. «The idea is to do justice to these songs. Songs that combine all the right ingredients that should have put them on radio playlists when I was growing up or at least in the cases of more adventurous DJs» (HHV 2018).

Having an ear for «hits that never were» – or, perhaps better, hits that were not allowed to become, due to the restrictive music policy of the radio – is exactly what Rodrigo’s work is about. He is re-writing music history by helping to prepare releases like Onda de Amor, promoting a fresh view on a part of Brazilian music history for Brazilians as well as an international audience, given the fact that Soundway Records operates from London and distributes worldwide.

How to Decolonize Pop Music?

The following questions remain crucial for music history writing – and crucial as well for decolonizing pop music: where, how, and by whom is a revaluation of historical pop music undertaken? Especially of non-Western historical pop music? Who can initiate a new appreciation? Who owns and administrates the archives? Who is writing the canon, who the history – and based on what? The crucial power and decision-making centers for pop music discourse are still located in the U.S. and Europe.

Let us have a closer look at an example. Despite of several Turkish publications about the pop music history of Türkiye (Erkal and Yillar 2014), with a first one titled Türk Pop Müziği Sanatçilari Ansiklopedisi published as early as 1978, the first prevalent international pop music history of Türkiye in English is Daniel Spicer’s The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion: Anadolu Psych 1965–1980 (2018). Spicer is a music journalist and editor of the well-known British music magazine Wire. The decisiveness of his book has to do with the discursive position of the writer, with the fact that it is written in English, commonly and globally used as an academic language due to its colonial history, and that there has been practically no book about the subject in English published until now in Türkiye or from a Turkish scholar. Thus, Türkiye has hardly participated in the global pop music discourse – which is mainly held in English or in French.

According to Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung’s position – developed in his Berlin-based project space Savvy Contemporary, where he recently reclaimed a genuine African physics – a truly extensive approach to decolonizing pop music should not only deal with writing a non-Western pop music history, but with doing it in an appropriate way – for example, when writing a genuinely African pop music history one should proceed from an African perspective, working off their own musical past and evaluating it. Being a non-African and living in Europe, I myself can do something like this only in a very limited way, nonetheless I can support such a pathway. This text itself is hopefully a kind of support.

Coming back to questions of evaluation, which are always at the same time questions of hierarchy and power: who is writing the history of global pop music? Primarily it is the Western world with its institutional agents such as journalists, editors, scholars, as well as label owners with their re-releases, and collectors buying original and/or re-released records. So how does Western pop music history evaluate non-Western pop music? In general, not very well – at best as exotic, if it is not ignored. Simon Reynolds in Retromania (2009) as well as Diedrich Diederichsen in Über Popmusik (2014), two seminal publications on pop music from recent years, tend to conclude that non-Western pop music has the «right» intentions but is realizing them badly by merely copying Western pop music with doubtful equipment, doubtful recording processes, and doubtful musical quality. Later on, Simon Reynolds continued to attack the value of non-Western pop music in his article on «Xenomania» (Reynolds 2013), using a rather colonial vocabulary: «[…] what all these exotic dance genres share is impurity: they are bastard and creole children […]» (ibid.).

Unquestioned benchmarks from a Western perspective remain mainly white, male Western pop musicians like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Elvis Presley, etc. Non-Western pop music is compared to their music and easily dismissed: it seems far from the original regarding central aspects of pop music – such as the vocals (if in English at all), music graphics on the sleeves, fashion, etc. – in all a weak copy of Western originals. Again Reynolds sets the agenda of putting down non-Western pop music when he calls it «heavily influenced» by Western pop music, following «the template laid down by their British and American arena-touring models as closely as possible.» As a result, non-Western pop music «provides a distorted mirror image of Western pop: in other words, a slightly askew, exotic-but-ultimately-familiar version of things we already love» (ibid.).

Eurocentric Devaluation

This point of view, which only registers the borrowing and copying from Western originals, serves to devaluate non-Western pop music and generates a colonial way of music history writing with music divided into first-class Western pop music and second-class non-Western pop music. This division reflects, and conforms to, the greater dividing project of colonialism: classifying people into first-class Western people and second-class non-Western people. In doing so, the hierarchical and classificatory project of missionary work is continued, as explained and critically outlined by Jean-Marie Teno in his documentary Le malentendu colonial (Cameroon, France, Germany 2004). As Teno shows, certain rights are demanded and claims are staked by the colonial project of classification, positions are defined and evaluations are made, which then, no wonder, always favor the superior class and disadvantage the inferior.

Another possibility is that the non-Western elements of non-Western pop music become an exotic value, to be savored like part of a special dish, just like you are willing to accept curry in a curry dish as a welcome change to the domestic cuisine. And not to forget the projecting Orientalist gaze in the sense of Edward Saïd, with all its yearnings and fears, mystifying the non-Western elements. Yet, we should also not forget the depth of ignorance on this topic. One can devaluate whole continents and their musical productions by simply ignoring them. Condor, the airline, has done so with their maps of musical styles and deeply Eurocentric non-sense comments like: «Depuis les années 1990, la majorité des genres musicaux s’est développé en Europe.» It is interesting to cast a closer look at Condor’s mapping of the musical world, where the U.S. and Europe are the leading continents, full of inventions of musical styles, whereas Asia, for example, has obviously big parts with no musical invention at all, or where merely non-styles such as Karaoke are mentioned.

The Turning Point

So far we have not discussed the actual positions and intentions of non-Western musicians. In the 1960s and 1970s many of them were indeed fascinated by the new electrified and electronic pop music of the Western world. The electrification of music served as a symbol of the modernity they were longing to be a part of. However, the musicians did not follow a simple borrowing or copying approach to Western music, but a hybridizing one. They combined numerous elements of their own musical culture – such as language, lyrics, composition, instruments, rhythms, harmonies, and melodies – with elements of Western pop music to forge something new, a common thread, which transcended their traditional music culture as well as Western pop music: hybrid pop. Prime examples for mixing and combining traditional indigenous musical structures with global Western musical structures are genres like Anatolian Rock or Ghanaian Highlife. Their hybrid pop points to a specifically non-Western modernity, a multi-local position of another modernity. Hybrid pop allows musicians as well as listeners to participate and identify with global modernity without losing their local, regional, or national identity.

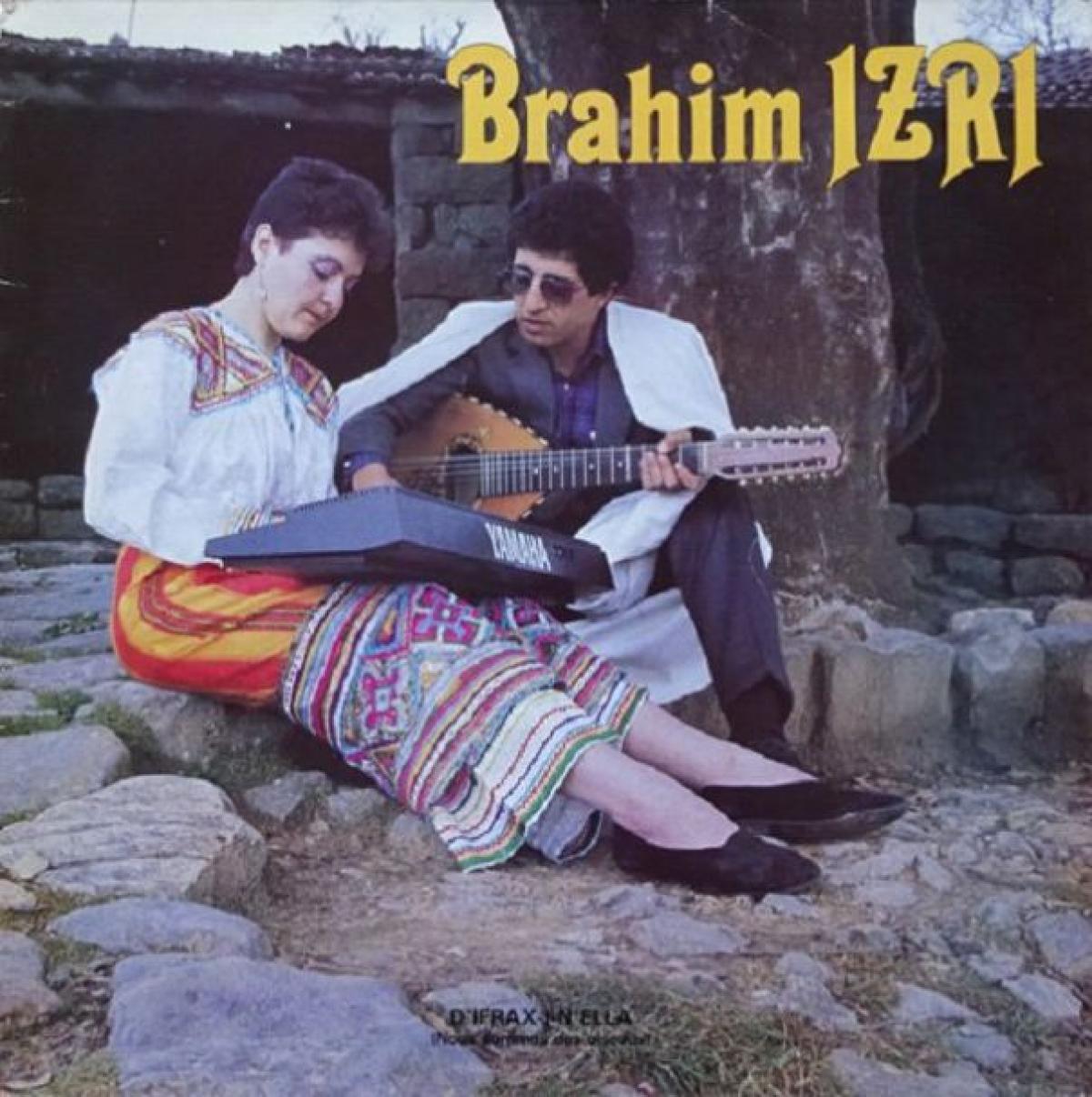

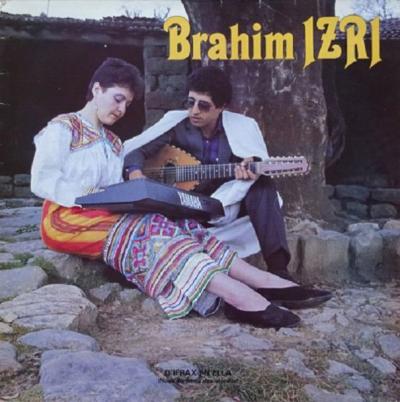

As an example, look at the sleeve for Brahim Izri’s record, D’Ifrax-I-N’Ella (1988, image 5). It announces what happens musically on the record by presenting the combination of modern urban and traditional rural clothing as well as the combination of modern synthesizer and traditional Algerian mandole. The record sleeve promises a kind of music that gives us both, by juxtaposition and by amalgamation: a «tradi-modern» music, including the Algerian past and transferring it to an Algerian modernity.

Modernities Can Differ

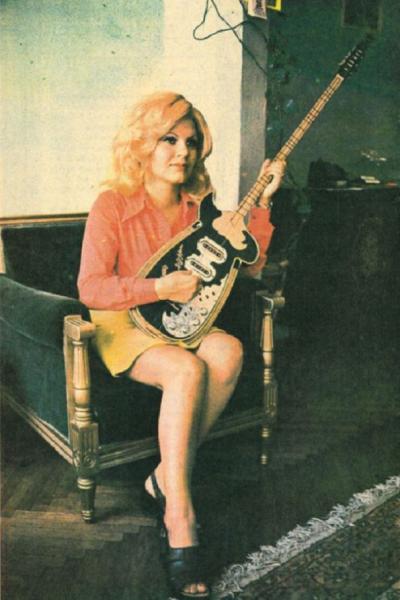

Another downright symbolic example is offered by the instrument featured on the already mentioned Saz Beat series on Global Pop First Wave. The saz is a traditional Oriental string instrument, by optics and sound in between a sitar, a lute, and a guitar. During the 1960s the saz was electrified by pioneering Anatolian rock musician Erkin Koray and pioneering Arabesk musician Orhan Gencebay (Baysal 2018) and subsequently played in a more Western way, like an electric guitar, using distortion and wah-wah effects. Listen, for example, to Cengiz Coskuner’s instrumental «Samsun’un Evleri» (1973) (omzbr 2016), re-released on the compilation Bosporus Bridges Vol. 3 by the Berlin-based label Black Pearl (2019).

The composition of the tune relates to a Turkish folk song, provided with drums and electric bass as well as with two electrified sazes – one for rhythm, one for lead – played with a warm distortion and using the wah-wah pedal in a rock music style. Here both are included: electrified urban modernity and Anatolian rural culture, pointing toward an electrified rural-urban, different modernity. The electrified saz meant a lot to the musicians back in the days, even on record sleeves and promotional photography they proudly displayed this instrument, shifting it from an electrified rural modernity to an electrified urban modernity (images 6 and 7), and even to an electrified super-modern modernity by inventing new types of a double and a triple neck electric saz-guitar (images 8 and 9).

The compilation series The Trip. Psychedelic Music from the Hippie Trail Pts. 1–4 (2015–2016), released on Global Pop First Wave, offers further examples for different concepts of hybrid pop, a different mix ratio within the hybrid constructions. The greater the distance from Europe into Asia gets on the Hippie Trail, the higher the amount of non-Western, indigenous elements in the music. This is not only because of curatorial choices, but due to changes in the mix ratio of the music itself – not all of the time, of course, exceptions do exist. There also exists another construction form of hybrid pop, though, not as an amalgamation but rather a co-existence of the starting substances, like in Niama Makalou et African Soul Band’s Kognokoura Drissa Coulibaly (1980) (TheLasphere 2011). Elements from Malian music are placed beside Afro-American disco-funk, like two separated layers, so you can listen to the same song as a rather traditional song from Mali or as an up-do-date piece of disco-funk.

Finally, we should note that there are forms of hybrid pop existing in the Western world itself. Listen to the Spencer Davis Group and their song medley «Det war in Schöneberg/Mädel, Ruck Ruck Ruck» (1966). Here Anglo-American rock’n’roll is hybridized with the German treasury of songs. Hybrid pop music is not exclusive to non-Western pop music, although it is much more likely to be found there.

Vanishing Point: Combining Local and Global

If we return to the title of this text, the questions of decolonizing pop music and of rewriting global pop music history are closely connected: a decolonization of non-Western pop music can only be achieved with a new presentation of global pop music history as both pop music history and hybrid pop music history. This presentation would also need local perspectives on music history, for example an African, Arabic, Turkish, Brazilian, etc. pop music history.

In doing so, specific functions of pop music should be addressed critically to understand them. During the Nigerian Biafra Civil War (1967–70), for example, pop music was encouraged by the military forces to serve recruitment purposes as well as the musical promotion of an African modernity (Now-Again Records 2016, Alapatt and Ikonne 2016). In this case, pop music was militant music – just not that kind of Western military marches one would expect as official music to produce discipline. Sexualized funk and soul music was used as an official music to attract and seduce young people to join the military or for soldiers to stay in it and fight. Even here, in the realm of the military, there is another modernity to be glimpsed.

While currently global pop music history is being rewritten, this is still a fragmented effort. When you look for the bigger picture, global pop music histories are mostly either oriented toward structures and general principles, avoiding the local details, like Motti Regev’s Pop-Rock Music (2013), or publications are more oriented toward contemporary phenomena, like the Berne-based platform Norient.com. Other major attempts are British publication series like Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Global Music Series. Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture, and Routledge Global Popular Music Series (Horn and Shepherd 2003, Campbell and Wade 2003, Fabbri and Plastino 2013). Still I am sure that rewritings of global pop music history as pop music history and hybrid pop music history will appear soon. Why? The tendency of so many non-Western pop music archeological labels to extend to a global level, supported by important archives for traditional non-Western music like the Amar Foundation for Arab Music, as well as the approved musical qualities of original and re-released hybrid pop music can no longer be ignored.

Who Sets Ethical Standards?

And so it comes to an ambivalent development: on the one hand, the musical qualities of historical hybrid pop music are fed into contemporary Western pop music, mostly via sampling in hip hop and Afro house. On the other hand, there is a new interest for non-Western pop music, in its countries of origin as well as in Western countries, which gives quite a few musicians the opportunity of a second career and quite a few musical styles a refreshment and continuation. Take, for example, The New Generation of Turkish Psychedelic (2016). Here Ercan Demirel, born in Türkiye, raised in Germany and Türkiye, and living in Germany now, has compiled contemporary Turkish (post-)psychedelic music for fans of historical Turkish psychedelic music worldwide. And even an American hip hop act like the Hispanic group Cypress Hill will go global today, as can be heard and seen in their current video «Band of Gypsies» (Cypress Hill 2018), which includes the Egyptian electro chaabi rappers Sadat and Alaa Fifty.

Most important of all, the globally approved qualities of hybrid pop music lead to a new self-image, a new identity in the non-Western world and its diaspora, as its respective musical past and culture is no longer regarded as something inferior, but as something that earns and receives recognition and appreciation on a global level. This process is pushed – which shows its ambivalences – by Western and non-Western groups with different aims and intentions. Ercan Demirel’s compilation The New Generation of Turkish Psychedelic is made from a completely different spirit than Cypress Hill’s «Band of Gypsies», and yet they both deliver contemporary hybrid pop.

Nonetheless it is the mentioned aspect of revaluation that is probably most important, at least as it concerns the decolonization of (non-Western) pop music. This is relevant even for the areas of pop music that present a problematic complexity, such as the use of pop music as militant music when Nigerian pop music developed in quality within an – ethically doubtful – military context. However, such complexities and contradictions have not been unknown in Western music history, if we just think of the war-loving Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his avant-garde circle of Futurists at the beginning of the 20th century. The Futurists would have been delighted – unfortunately – to see their music used as militant music. Anyhow, do we have the right (ethical) standards and a justified position to judge these aspects outside the Western world, when we have similar difficulties inside the Western world? Should there not be an African music ethics developed and assessed here?

The Cooperative Approach

Let us go back, once more, to Global Pop First Wave and my work for this label. At present, when it comes to decolonizing approaches, one can observe more and more cooperative working structures, including Western and non-Western partners on a preferably equal level. Tendencies to exclude Western people, especially white ones, like explicitly proposed in the South African web series The Foxy Five, are still the exception.

I regard the cooperative approach as the model for my own future decolonizing work for Global Pop First Wave and related curatorial and scholarly efforts. At present, my partner Cornelia Lund and I collaborate with the Turkish scholar and curator Banu Çiçek Tülü on the project «Hybrid Glamour – Turkish Pop Music Images. The Music and Its Communication Design: Record Covers, Photos & Posters & Ads in Magazines, Cinema Posters, Music Performances in Films & Clips 1960s – early 1980s». It is a scholarly-curatorial project, with an extended team that includes Mona Mahall and Asli Serbest as well as a wider Turkish community network with additional input from Murat Meriç, Erbatur Çavuşoğlu, Hilmi Tezgör, and many others.

With our independent media art and media design platform fluctuating images, Cornelia Lund and I are planning to extend our cooperation with African partners like the Senegalese platform for cultural production Wakh’Art in Dakar. Currently we are working on the exhibition project «Connecting Afro Futures. Fashion x Hair x Design», for which fluctuating images is cooperating with the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Applied Arts and Design) Berlin and Wakh’Art.

Because nothing is more important to us than mutual exchange to achieve a critical and self-reflexive decolonizing practice. Here we treasure the continuous dialog with Luiza Prado and Pedro Oliveira, two Brazilian agents of the international group Decolonizing Design. Their input is on a next level reflecting and criticizing decolonial discourse and the different interests involved in it. As every intellectual practice, decolonial thinking needs attentive revaluation itself.

How Does Streaming Affect the Future of Music?

And a last point: when we consider that streaming is the most influential way of hearing music today, new questions are turning up: «Will our digitally connected music world result in a globally informed pop monoculture, created at the whim of Western streaming companies?» (Pelly 2018, 32) the New York-based writer Liz Pelly asked recently. She points to the fact that music-streaming services produce a lack or even a loss of context, bringing historical and contemporary music to one and the same level, evening out the geographical differences: music from nowhere/anywhere and timeless/from any time. Music from the Non-Places of Marc Augés? Developing a historical sense becomes difficult here. But this annihilation of history concerns images as well as music, it concerns cultural production and its perception in general. Music history writing has to take this cultural practice in mind and has to deal with it – streaming history against music streaming.