In her videoclip «Pata Pata» Nigerian singer Temi DollFace makes fun of women who escape from their stuck relationship by throwing themselves into consumption, creating their own bubble of materialist desires. By advertising fantasy products, DollFace encourages them to finally break up. In her clip (dir. by James Slater) she refers to Nigeria in the 1970’s: A time, where the economic boom introduced the possibility of material prosperity. Was the relationship between the government and the Nigerian public similarly damaged as the partnership of the woman in the clip?

The tangible signs of progress and abundance ratified [Nigeria’s] new prosperity with visible evidence, producing a national dramaturgy of appearances and representations that beckoned toward modernity and brought it into being. Or so it seemed. In what became the magical realism of Nigerian modernity, the signs of development were equated with its substance.

(Apter 2005, 41; emphasis added)

In her delightfully retro-styled video for «Pata Pata», Temi DollFace bats her eyelashes and hawks whimsical household products designed to aid women whose romantic relationships have gone stale. At the same time, she declares «it’s over, pata pata» (completely) with her own significant other. While the song’s commentary on fizzled-out romance is both relatable and relevant, the stylistic and musical references to 1970’s Nigeria can also spell out a critique of the oil-driven development of the Nigerian nation-state. Like lovers who refuse to acknowledge problems in their relationship, the Nigerian state’s dependence on oil revenue silently exacerbates the economic and political challenges its people face. The commodity fetishism on display in «Pata Pata» parodies the commodity fetishism, real and symbolic, of Nigerian governance.

Temi DollFace begins Pata Pata with a provocative question: «Pour me a drink and I’ll tell you a lie, baby, what would you like to hear? That I’m in love with you and all the things you do? You know that wouldn’t be sincere.» The speaker in the song has had it with her partner: the relationship is boring, «the thrill is gone,» the speaker is fed up with the trouble her partner has given her («I dey tire for your wahala»), and she «can no longer compromise.» Though they have been stuck for some time, the speaker has hesitated to approach her partner because «I don’t wanna make you cry.» She sarcastically offers, «We can go on pretending, baby it’s all right,» but she realizes that «it’s over (over pata pata).» By the end of the song, the speaker is sure that she wants to end the relationship, altering the lyrics slightly: «I’ll tell you a lie, baby, what would you like to hear? We can go on pretending…» In other words, it has become a lie to say that the speaker can continue the masquerade of the relationship.

Alienation, Advertisement and Alerts

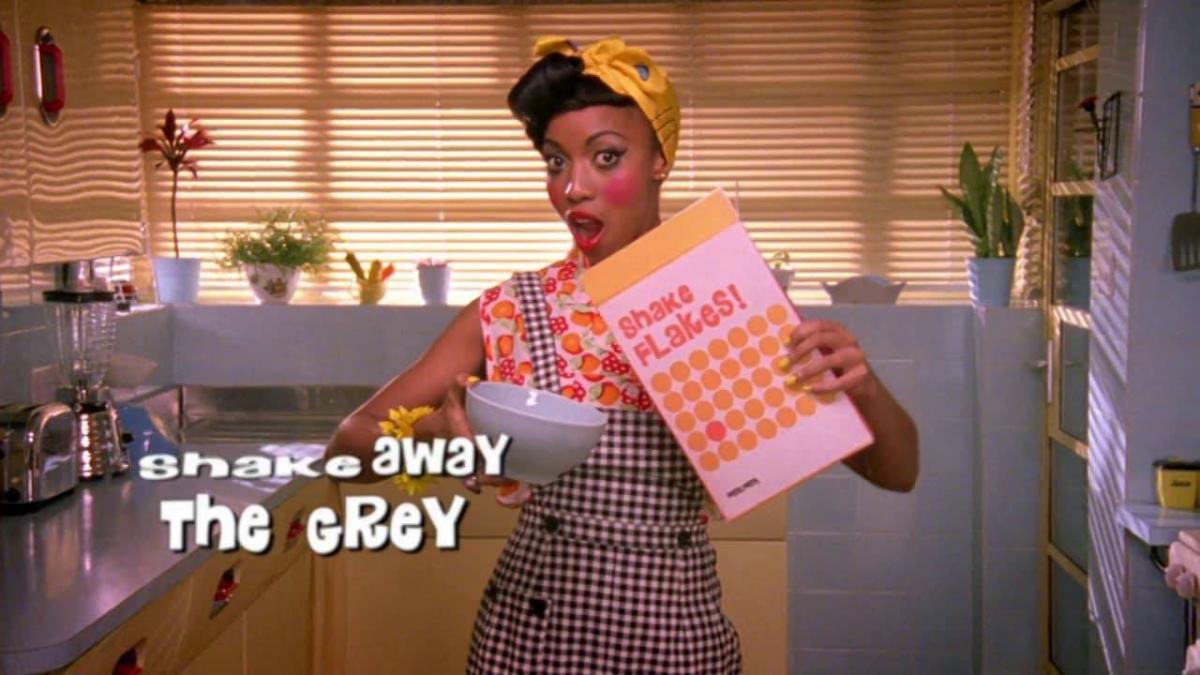

The music video for «Pata Pata» addresses not the speaker’s partner but rather women who find themselves in similar situations. Using a series of advertisements for Pata Pata brand products, Temi DollFace encourages women to respond to their relationship problems directly instead of letting them fester. The video advertises eleven products, ranging from washing powder («e dey commot all doti stain, including de man sef» – it gets out all the dirty stains, including even the man himself) and shampoo («Wash dat man commot for your hair» – wash that man out of your hair) to the Patavac (a vacuum cleaner that «sucks up bad vibes») and the Pata Pata Getaway Car («Make your move, pack your bags, it’s over»). Some of the products are typical household items that have been repurposed for dealing with relationship problems, such as the Pata Pata Knife, which pledges to «cut off your wahala sharp-sharp» (cut off your troubles immediately). Other products are new inventions specifically for dealing with stuck relationships: the Pata Pata Bedsplitter is for women whose partners no longer satisfy them sexually, and the 5D television offers «escape to a new world» beyond that of the relationship. Throughout the video, Temi DollFace and her dancers entice viewers to participate in the Pata Pata Dance, which comes with its own tutorial in three volumes and includes the popular Azonto moves.

As Derica Shields astutely points out (see post at Okayafrica.com), Pata Pata’s music video uses these mini-advertisements to poke fun at materialist desires for instant gratification by way of consumer products. The Pata Pata Knife claims to be sharp, but as far as Temi DollFace shows us, it can only cut a banana. Thus, the video humorously reminds us that material objects can only go so far (that is to say, not far at all) in helping navigate the complexities of human relationships. In Pata Pata, the speaker’s relationship has become a bubble with no interior substance, in which the partners deceive each other and themselves into believing that «it’s all right;» similarly, the Pata Pata products become a bubble in which the consumer can deceive herself that her relationship problems can be resolved completely and immediately with face cream or «Shake Flakes» cereal. Instantaneous solutions appear attractive, but closer examination reveals that they do not hold up under the demands of complicated human problems.

Paying Reverence to Fela Kuti

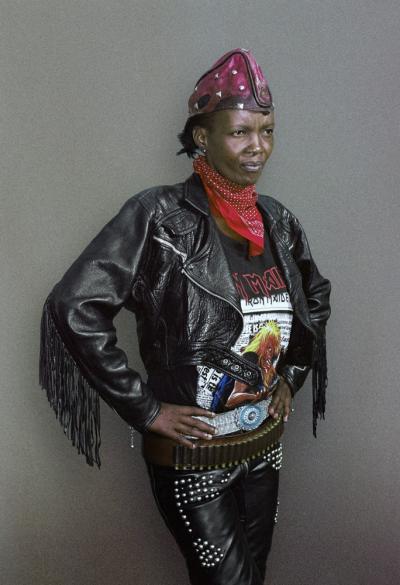

In addition to its Western retro-styling, «Pata Pata» contains a number of references to Nigeria in the 1970’s, a period of rapid modernization (according to the standards of the colonial powers) and economic boom. Those references include the «pata pata» choral response throughout the song that sounds like a sample from one of Fela Kuti’s tracks (for example, here starting from 0:33), and the elaborately costumed dancers whose face paint and accessories resemble Fela’s Kalakuta Queens (backup dancers/singers/wives).

Fela’s influence can also be heard in Temi DollFace’s Pidgin lyrics – Fela’s Afrobeat was some of the first popular music in Nigeria to intentionally use Pidgin. This allowed him to broadcast his messages across the newly independent, linguistically diverse nation. When we turn our attention to the 1970’s Nigeria referenced by these elements – call and response, costuming, and language – we find that a strikingly analogous bubble was forming around the strained relationship between the government and the Nigerian public. As in «Pata Pata», consumer products masked the strain of this relationship.

Damaged Relationship with the Government

The modernizing bubble promised all the comforts that the colonial powers enjoyed – provided on the slippery surface of petrodollars and petronaira (Apter 2005). Following the discovery of oil in southeastern Nigeria, the government joined OPEC and enjoyed the benefits of high oil prices (even as Americans went through a recession). The initial spectacle generated by Nigerian oil was that of economic takeoff…based not on the accumulation of surplus value…but on a specific form of excess – one of oil rents and revenues that underwrote the importation of staples and luxury goods, as well as various white elephant projects that produced only negative returns (Apter 2005, 14).

Although oil money introduced the possibility of material prosperity, Nigerian consumers bought consumer products from abroad, and the Nigerian economy leaned heavily on oil rather than developing a manufacturing sector that could sustain the economy through fluctuations in the price of oil. The consumer goods dangled the possibilities of immediate gratification before Nigerians’ eyes: Apter writes of the popularity of a Korean-manufactured television («The picture’s so real – you’re part of the action») and the Polaroid camera, the «instant picture camera that produced push-button images of tomorrow’s world electronically and automatically ‘before your eyes» (Apter 2005, 41). The presence of such modern appliances built up an illusion that the Nigerian economy could sustain this level of consumption, and that the nation-state, renting out its single resource, would remain politically and economically viable. «The magic of Nigeria’s oil-fueled modernity, like the self-developing Polaroid picture, was instant, effortless, and above all spectacular,» Apter concludes (Apter 2005, 42).

However, the influx of petrodollars and the renting-out of the nation’s only resource to oil companies led to a body politic driven by dubiously-elected leaders (and dictators) distributing spoils to ethnic, religious, and geographic clienteles. As the nation-state centralized, the oil money was consolidated at the federal level and trickled down at all levels of government. Added to the political instability of successive dictatorships and coups, endemic corruption eroded the trust of the Nigerian public in the government. This continues today – the Nigerian economy and government are still dependent on oil, and people have little faith in the ability of the state to provide for its citizens.

Just like the speaker’s relationship in «Pata Pata», the relationship between the people and the government is substance-less and for show only – and, as in «Pata Pata», consumer products cannot bring about instantaneous repairs. Pata Pata’s critique is especially relevant in light of the increasing urgency of Boko Haram’s advances in the northern part of the country, as well as the impending (and just-postponed) 2015 elections, which pit the ineffectual incumbent President Goodluck Jonathan against former military dictator General Muhammadu Buhari. However, popping the increasingly perilous bubble with «it’s over,» as Temi DollFace does, is not an option. In the absence of a Pata Pata Getaway Car for (most) Nigerians to escape the damage done by their troubled government, the problem of the bubble will have to be solved independent of quick material fixes.