Dard I Door

Bassist Reza Askari and poet Tanasgol Sabbagh will meet in June 2022 in Berlin as part of Klangteppich (Festival for music of the Iranian diaspora). Their performance Dard I Door addresses their different family histories, connected with their shared Iranian descent. In this prelude to the Berlin performance, Tanasgol weaves experience, memory, and narrative into one another, switching language between English and German, allowing uncertainty about what is actually said and what is imagined.

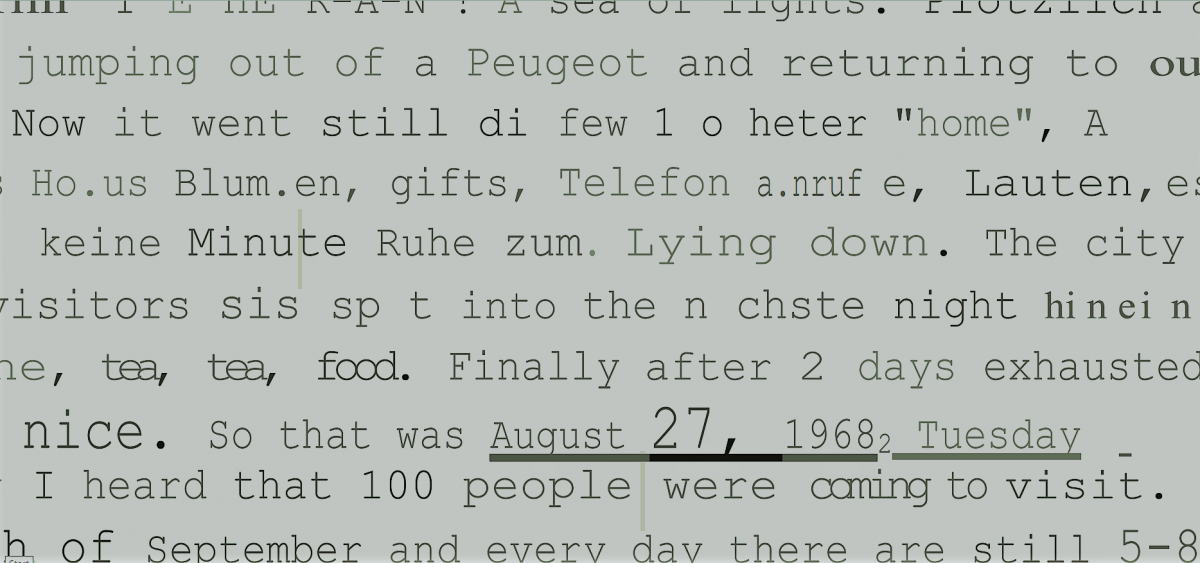

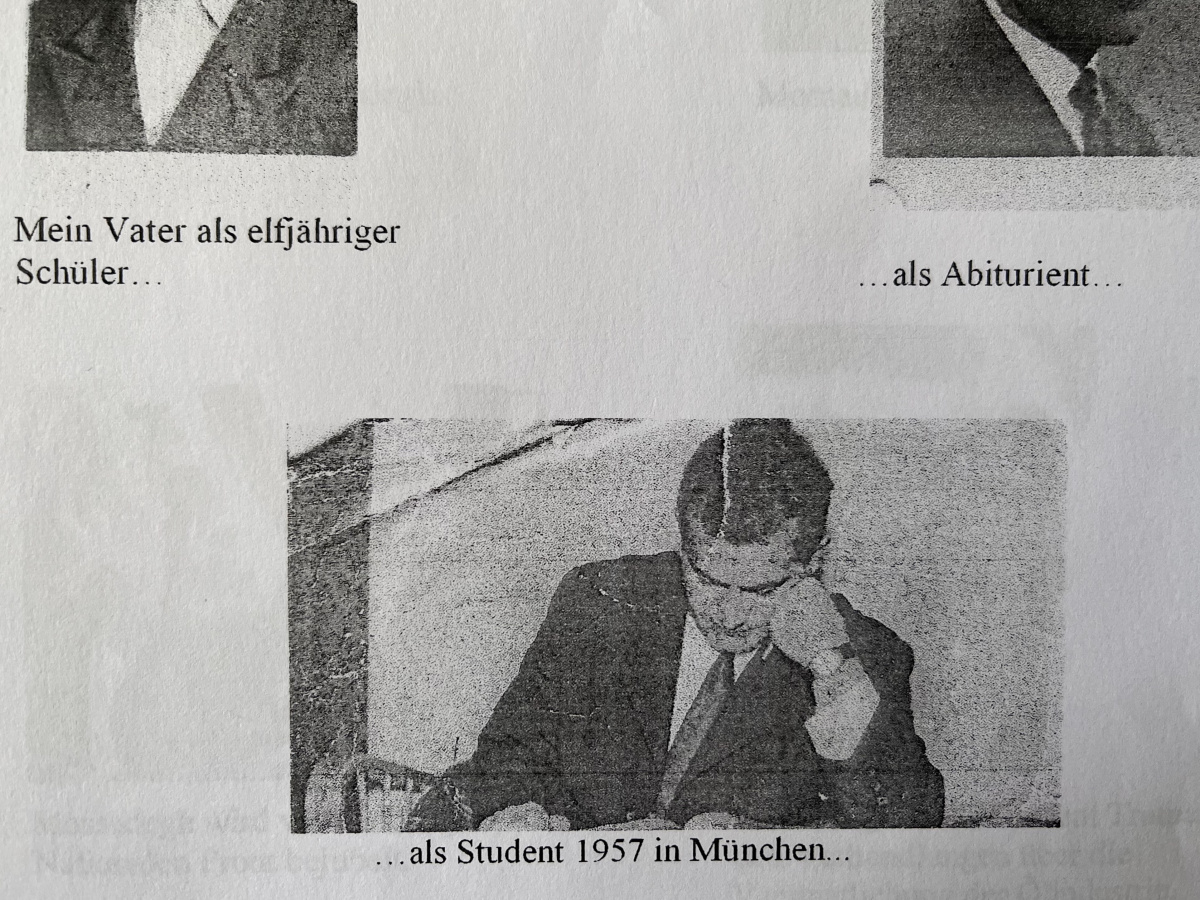

Reza Askari’s father left Iran as an active supporter of Mohammad Mossadegh1 in the late 1950s, and began studying medicine in Germany. Tanasgol’s family took part in the protests and struggle against the Shah’s regime in the 1970s, and fled to Germany and Canada in the years after the revolution. The performance at the Klangteppich festival aims to create a dialogue between experienced pain and narrated grief by using poetry and music, by retelling and inventing stories.

There must be a way of tying together what my eyes can hold: I can see myself learning that there is an end to things, while a flight attendant explains how that bag should be used, and my mother using it: Hunched over, her veil coming loose. I see the flight attendant looking for a pill. I sometimes see them nervous, I see them calm sometimes, sometimes I see my one year old sister crying, someone must have held her, I can’t see myself.

I don’t necessarily remember us in the physical order of things, like in a dream, I know we are there, and if I want to, my imagination morphs the idea of the flight attendant, the idea of my mother into flesh.

I don’t remember seeing those bags on my more recent flights. I have stopped noticing them, now I only remember them missing. I can see my mother, twenty-five years old, my sister, one, our matching dresses.

I can’t see myself.

There must be a way of tying together what my mind can hold, what my eyes can hold is plenty, I don’t need to ask. I only gather pieces of information falling out of anecdotes, as if a truth only counts, when you stumble upon it. I only gather what they leave.

The dresses our neighbor had tailored for the occasion, my boyish face, my father’s face in mine, twenty-five years ago, bodies moving.

Das geschneiderte Kleid, mein Jungengesicht und eine Erinnerung, die mir jahrelang erzählt wird: Wie ich mich vor der Abreise von den Verwandten wegdrehe, dass sie mich nicht weinen sehen. Wie ich lüge und sage, dass mir bloss etwas ins Auge geflogen sei. Wie ich sie zum Lachen bringe. Es wurde mir so oft erzählt, dass ich mich erinnere.

Soundsoviel Mark pro Minute Fernanruf für dieselbe Szene aus immer anderen Tantenmündern: Eine bald Fünfjährige weint, weil sie weiss, dass sie geht, eine bald Fünfjährige dreht sich weg, sie habe bloss Sand im Auge. Eine bald Fünfjährige geht. Auch so endet Liebe: Ein Bild so häufig beschwören, bis es nur ein Bild ist.

Ich habe den Sand dann behalten.

I kept that sand.

Es muss einen Weg geben, zu verbinden, was ich nebeneinander denken kann: Reza und ich sprechen über Zoom über die unterschiedlichen Hintergründe unserer Leben. Über unsere Familien.

Reza hat mir das Paper zugeschickt, das er zum Schulabschluss über das Leben seines Vaters in Deutschland geschrieben hatte. Über die politische Lage Irans in den 1950er und 1960er Jahren.

In den Fussnoten schreibt er:

Nach Rücksprache mit meinem Vater.

Laut einer Aussage meines Vaters.

Er schreibt:

Da mein Vater aus persönlichen Beweggründen davon Abstand nimmt, die damals geschehenen Ereignisse zu schildern, ist mir die Möglichkeit nicht gegeben, nähere Informationen bezüglich –

In den Fussnoten schreibt er: Mein Vater.

You laughed at your father’s funeral.

You were the only one of you there.

Your family had left Iran in the years before: Your siblings fled, your parents followed, your father was sick. You were the youngest, you haven’t caused enough to leave, so you stayed.

When your father died in Winnipeg you laughed in Sāri2, at the funeral held in his honor. You laughed so hard, you had to hide your face in your black chādor, your failed attempts at suppressing laughter, looking as though you were weeping. You laughed so hard, there were tears streaming down your face. A few years later, you took S and me, and left.

Reza sagt: Seit er tot ist, ist mein Vater mein bester Freund.

Wir planen unsere Performance im Juni, ich mache mir Notizen, die ich später nicht wieder finde. Ich sage: Unsere Familien kamen aus unterschiedlichen Richtungen auf denselben Feind zu. Wären sie dich in Deutschland begegnet, hätten sie sich so lange an ihre Sprache geklammert, bis sie klar gemacht hätte, wie weit sie voneinander weg standen.

Ich frage ihn nicht, warum er über seinen Vater geschrieben hat. Ich frage ihn nicht, wie es ihm gelungen ist.

There is a sound recording on my phone.

I’ve recorded my mother and her sister fighting. I named it dard-e moshtarak, mutual pain, after a poem by Shamlu3. She visited us last Christmas, and they had a fight.

In this fight my mother is 7 and my aunt is 17, and it is 1979.

In this fight, the years pass, and my mother is 13, and her sister is 23.

In this fight, two generations try to trace back history, and my mother is 17, and my mother is 20 and my mother is 25, and my mother is in Germany and my aunt lives in Canada, and a political issue becomes a family issue, and it is all true, and each one of them is right, and each one of them is wrong, and my mother is 50 years old, and I turn on my phone and I record all of it, and it is Christmas, not that it matters, and they’re both exhausted, and there is my cousin and I, stroking our mothers’ arms on the sofa, each of us translating accusation into love.

I never listen to that recording.

There must be a way of tying together, of mending something.

There must be a way of letting go.

This text is part of the Norient Special «Klangteppich: Voices from the Iranian Diaspora and Beyond», published in the run-up to «Klangteppich: Festival for music of the Iranian diaspora IV». The Special was curated and edited by Franziska Buhre. More on the projects and artists can be found here.

Klangteppich IV is funded by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation). Funded by the Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media) and the Co-Financing Fund Berlin.

Biography

Shop

Published on May 19, 2022

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topic

What happens, when artists move from one to another country? For example, when an Arab artist replaces the big tractors in her the village with big jeeps of the West.

Special

Snap