As an anthropologist and urban planning researcher with specialties in music and sound, we have combined our backgrounds to examine the politics of reconstructing soundscapes in Rio de Janeiro. In anticipation of mega-sporting events, the state has begun to remake and re-sound significant areas of the city. We are thus interested in the sonic implications, explicit and implicit, which have not been focused on in the rush of federal, state, and municipal investments in transportation, housing, public security, and favela infrastructure. In particular, we investigate attacks – through police repression and legal restriction – on the symbolic locus of funk carioca, the most popular music produced and consumed in the favelas and suburbs, as experienced through ethnographic field work.

Although named after one of the originators of Bossa Nova and the composer of «The Girl From Ipanema», Rio de Janeiro’s Antonio Carlos Jobim International Airport’s most distinctive sound is its announcer's voice. Since the 1970s, recordings of a husky Brazilian woman’s voice have announced the arrival and departure times and gate numbers for flights at Rio de Janeiro’s international airport. Íris Lettieri's smoker’s voice hisses and purrs numbers, times, cities, «departing immediately» in the sexiest, breathiest Portuguese followed by English, which she claims not to speak. Rock songs have been made about her. Japanese businessmen, apparently, have lost their flights listening to her (McCarthy 2007). The voice, chosen to exude calmness, though unexpectedly exuding sensuality, is part of an emerging crafted auditory experience of Rio, which in 2010 received 1.6 million visitors.

With Lettieri ringing in the ears, the typical tourist leaves the confines of the airport for Rio. The taxi finally arrives in the usual dropping off points of the Zona Sul, probably Copacabana or Ipanema, where the city’s main concentration of hotels and beaches is located. The sounds of car engines, buses and public transit vans in traffic during the day fade to crashing ocean waves at night, urban to ocean. Hotel elevators pipe in a Bossa Nova groove, while groups of buskers play samba along the beachfront. The scene resembles the soundtrack of the 2011 animated movie Rio, which played on the airplane.

Between the airport and the hotel, observant visitors might notice something odd from their taxi heading down the Linha Vermelha highway. There is a continuous wall of flimsy-looking opaque plastic adorned with designs of little kid paintings: the statue of Christ the Redeemer, the Sugar Loaf mountain, a flower bouquet. These walls, called barreiras sonoras, sonic barriers, separate the highway from the favelas of Complexo do Maré. The non-touristic favelas of Zona Norte with brick and mortar square-like constructions, complete with blue water tanks on rooftops, greet all international visitors to Rio. The barriers are supposed to protect the favelas’ residents from the noise of the highway. They are interpreted, however, as «protecting» the highway from the sight of the favelas. Part of them has already been torn down. As a photographer explained at the Museum of Maré, «None of the scenes on the walls depict anything of their reality of Zona Norte». The walls have already been the subject of public opinion research in the Maré, and were a major topic of discussion at a September 2011 seminar entitled «Walls, Removal, and Urban Makeup» (URL accessed on 13.04.2012). The barriers fit Teresa Caldeira's critique of São Paulo as the «City of Walls» (2000). In Brazil, Caldeira contends, the beginning of democratization and the increasing spatial proximity between working class and elite has lead to urban building practices, which increasingly eliminate common spaces through proliferation of various barriers and «fortified enclaves». The sonic barriers also create an auditory form of exclusion.

These walls are part of the preparations being made for the influx of international visitors for the World Cup (2014) followed by the Olympics (2016). Indeed, the Olympics have a long history of justifying brutal urban renewal policies that displace the poor or otherwise undesired (Davis 2006, 106). Most recently, Beijing walled off or razed its hutongs; Capetown razed townships. In Rio and São Paulo, favelas have been the target, with numbers of forced evictions and demolitions increasing as new infrastructure is prepared. Already, the Special Rapporteur of the UN Human Rights Council on the right to adequate housing has expressed her concerns about this matter all over Brazil, especially in Rio (URL accessed on 13.04.2012). The Maré barreiras are enlightening, however, as an example of sound as the pretext for walling off Complexo do Maré from the eyes of the world. In its attempt to create invisibility, the sound barriers are the most visible marker of the fact that sound politics are an under-explored aspect of ongoing debates about how Rio de Janeiro is being remade physically and that transformation’s social, political, and economic consequences.

As an anthropologist and urban planning researcher with specialties in music and sound, we have drawn on our combined 28 months of ethnographic and urban sociological research between 2006-2011 to examine the politics of reconstructing soundscapes in Rio de Janeiro. We met initially through our mutual interest in and research on funk carioca («funk from Rio», a local electronic dance music) and crossed paths in New York, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. Between 2010 and 2011, we both lived in Rio de Janeiro. Alexandra Lippman was engaged in doctoral research on music, intellectual property, and technology and Gregory Scruggs was engaged in urban planning and development research as a Fulbright study/research grant recipient. During our research in Rio, the state began to remake and re-sound significant areas of the city in anticipation of mega-sporting events. We are thus interested in the sonic implications, explicit and implicit, which have not been focused on in the rush of federal, state, and municipal investments in transportation, housing, public security, and favela infrastructure. In particular, we investigate incursions – through police repression and legal restrictions – on the symbolic locus of funk carioca, the most popular music produced and consumed in the favelas and suburbs. Despite its national popularity and international underground appeal, this genre has sparked the most controversy and the most intense control measures even as it is firmly woven into the city’s overall soundscape.

Sonic Casualties in the War for Rio

Over more than the last decade, funk carioca, which is referred to simply as funk, has become the most commonly heard music in Rio de Janeiro (Medeiros 2006, 99-100), vastly outpacing bossa nove and samba, the former is confined to tourist areas and the latter tends to follow a Carnival schedule. It is a largely youth soundtrack for personal consumption but especially for dancing when performed live. The basic, identifiable beat of funk – tamborzão («big drum») with its heavy Candomblé drums beatboxed or sampled via an MPC – can be heard in television advertisements for fast food, commercial jingles broadcast from storefronts, cell phone ringtones, beachfront car trunks, nightclubs of all stripes, and at traditional cultural events – such as Festas Junina («June Parties», a celebration of Brazilian rural culture) – over 1,000 kilometers from Rio de Janeiro. It also has gained currency abroad under the name «baile funk» through Internet-based dissemination, especially blogs, and a handful of independent record labels, club nights, and DJs, MCs, and producers who are based in cities outside Brazil. Since its inception, funk has undergone several cycles of national popularity, and it has become a commonplace to report that middle- and upper-class youth, not just favela youth, are listening to funk (Yúdice 2003, 129; Herschmann 2005, 114; Albuqerque 2007, 20-23). Originator DJ Marlboro played a birthday party for the son of Rio’s governor in 2008, and later that year former president Luiz Inácio «Lula» da Silva posed for a photo with the immensely popular all-female funk ensemble Gaiola das Popozudas (Philips 2009).

More recently, on August 30, 2011, artists celebrated on national radio the second anniversary of a state law declaring, «Funk é cultura (Funk is culture)» (URL accessed on 13.04.2012). The law was proposed in August 2008 and approved in September 2009. It is significant for its legal defense of funk as «a cultural and musical movement of popular character» that should not be treated any differently from other similar manifestations of popular culture, such as samba. Samba school rehearsals typically go well into the night and their non-amplified drum corps are very loud, although in residential neighborhoods like Vila Isabel, new rules regulate how late rehearsals can run. Placing funk on par with samba, Brazil’s national music since its coronation in the 1930s is a legal certification of a critical claim scholars have made for many years (Vianna 1988, Essinger 2005) and is a de jure, if not a de facto, recognition of funk’s similar trajectory to samba, from persecution to popularity. The law also lauds funk as one of the few cultural forms that leads to mixing between social groups, and samba has historically been seen as a keeper of social peace (Yúdice 2003, 112).

The law also specifically challenges legal discrimination against funk’s live performance, citing as justification for the legislative bill «laws that criminalize bailes and impede the staging of shows by judicial order or by will of the owners of venues» (Law Nº 1671). This legal protection is complemented by anti-discrimination claims – that funk should not be subject to prejudice – and a specific order that the Secretary of Culture, or similar public offices, should be the government’s representative agents toward the funk industry. The unwritten reference here is that the state’s security apparatus should not be the arm of the government interacting with funk, as has been the case historically. In doing so, the law endorses the argument made by George Yúdice in his seminal article on the style, «The Funkification of Rio», that the music serves as an effort by favelados (people living in favelas) «to clear a space of their own» and that «funk’s cultural politics [belong] in the terrain of conflicting public spheres» (Yúdice 2003, 130-132).

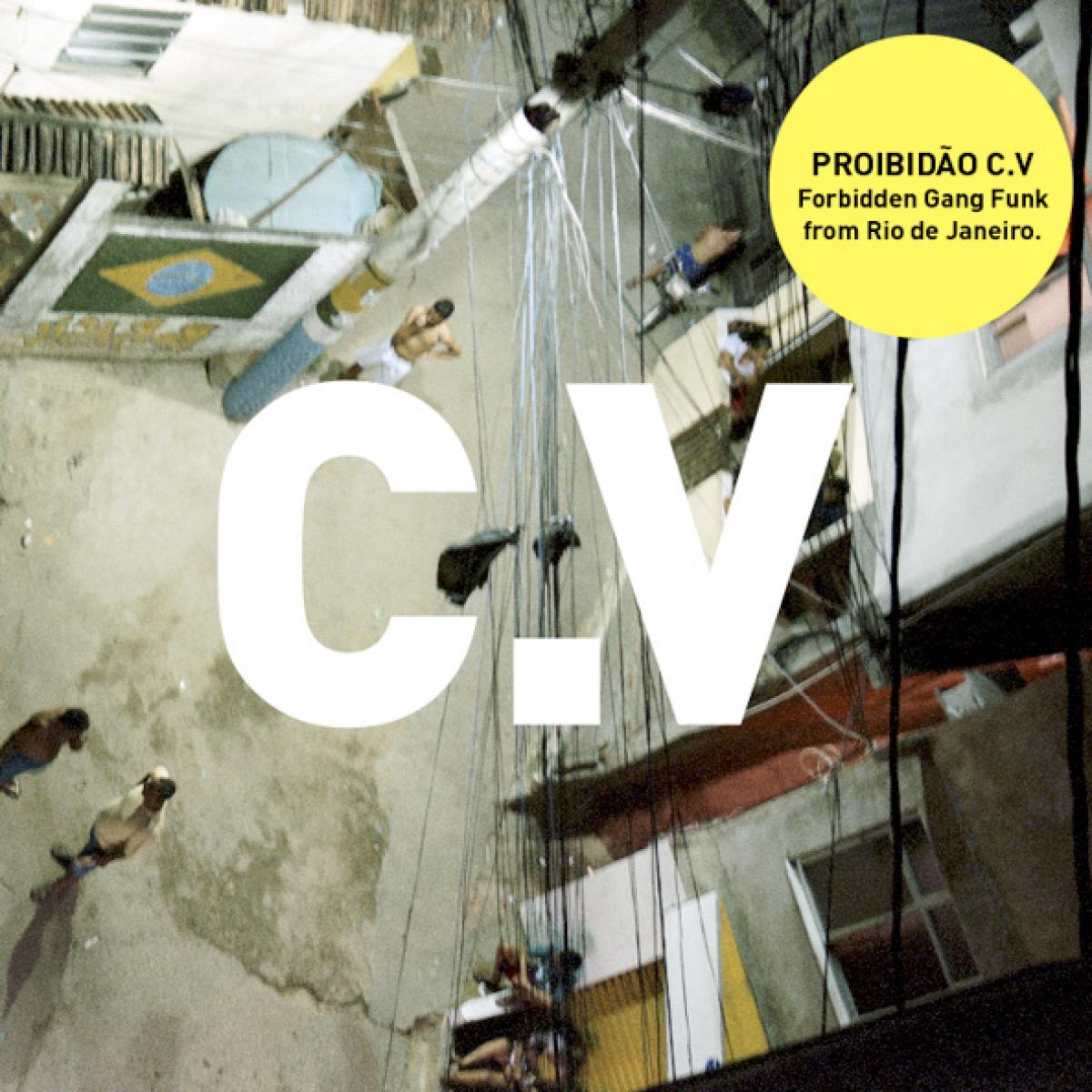

Funk thus exists in a paradox. It is, on the one hand, an essential and largely inoffensive component of Rio’s, and indeed Brazil’s, sonic landscape that has some degree of legal protection and positive social benefits. However, funk is clearly a plural music, whose different lyrical and musical sub-genres – light, pop, melody, putaria with its sexy, double entendre lyrics, and «gangster» proibidão with lyrics about violence and criminal factions– receive vastly different social and political treatment. In particular, funk performed live in favelas, a format which has often had a tenuous relationship with the law, has become the recent target of police programs that seek to bring favelas under the control of the state. For two decades, favela performances have been funk’s symbolic locus, as indicated through lyrical content (Sneed 2006; Lopes 2011) if not its most economically lucrative site of production, performance, or consumption (FGV 2008). But these hotly contested urban spaces are undergoing rapid change in advance of the city’s mega-sporting events that is creating new dimensions as funkification comes up against the specter of pacification.

While a constellation of federal, state, and local policies are in the process of remaking the physical and social landscape of Rio, the Unidade de Polícia Pacificadora (Police Pacification Units, or UPP) is the most publicized and most relevant for funk. The UPP is run by the Secretary of Security of the State of Rio de Janeiro, which is the entity responsible for the Military Police of the State of Rio de Janeiro. It began in 2008 and is currently present in 18 favelas, most of which are concentrated in the Zona Sul, Centro, and Tijuca, the wealthiest areas of the city. The Complexo do Alemão, a large complex of favelas that was invaded by the national army on November 25, 2010, will soon receive UPP but continues to be occupied by soldiers. The UPP’s goal is to evict the narco-traffic regime in favelas through overwhelming force and then to maintain a permanent police presence to ensure that public acts of drug trafficking do not take place. The general consensus is that drug trafficking continues behind closed doors.

The arrival of the UPP in favelas located in areas of economic and touristic value has also entailed the demise of bailes da comunidade, or community bailes funk sometimes financially supported by – and musically allied with – the narco-traffic regime. The state, through several laws and police actions, has long treated funk as an apology for crime and bailes funk as criminal events, as the «funk is culture» law addresses. The first baile to return to a pacified favela began in the Zona Sul favela of Ladeira dos Tabajaras. Reopening the baile was such a contested event that the weekend before the baile began, the police said that they received noise complaints, when there was not even a baile yet.

Several other pacified bailes have sprung up under strict sound and time controls – namely, lower than normal volumes and a closing hour of 2 a.m. on weekends and 10 pm to midnight on weeknights. Nightclubs in the formal city are not restricted and will generally run as late as they have patrons, easily ending at 7 a.m. When police cut the sound system at the Turano favela on August 14, 2011 because it continued after hours, the angered public responded with rocks, sticks, bottles, cans, and, possibly, Molotov cocktails, prompting a violent confrontation with police (URL accessed on 13.04.2012). Restrictions over volume and timing have become a new flashpoint between police and favela residents as the state’s forces of order attempt to impose control over the sonic manifestation of favela culture.

The UPP is an essential strategy in Rio’s security preparation for the World Cup and the Olympics, and fits the prophecy quoted in Mike Davis' Planet of Slums that the cities «of the Third World – especially their slum outskirts – will be the distinctive battlespace of the twenty-first century» (2006, 199-206). Recent conflicts over bailes are subsequent illustrations of how the «politics of frequency» occur «against the backdrop of a creeping military urbanism» (Goodman 2010, xv). Funk and other representations of «global ghettotech»:

Generate bass ecologies within underdeveloped zones of megalopian systems. As such, they have cultivated, with Jamaican sound system culture as the prototype or abstract machine, a diagram of affective mobilization with bass materialist foundation (Goodman 2010, 175).

Appropriately, mobile mega-soundsystems have traveled. Dick Hebdige, in his history of Caribbean music, writes of Jamaican sound systems in England with bass so numbingly amplified it brings «cool joy, a sedative high. Ice in the spine. No pain.» (1987, 90). Sonjah Stanley Niaah takes up this history with her analysis of dancehall's «performance geography». This geography «is built on an understanding that acts of performance are linked across space through ritual, dance movement, production and consumption practices, as well as the movement of aural and visual images» (Niaah 2010, 33). Moreover, Niaah frequently refers to dancehall’s repression by the state, especially attempts to silence the music through legal restrictions such as Jamaica’s 1997 Noise Abatement Act, as a way of limiting the cultural expression of poor Jamaicans.

The lineage is thus clear that funk, despite its different socio-political context (Jamaica and Brazil) though with underlying diasporic «Black Atlantic» (Gilroy 1991, 1996) histories, manifests the power and the threat of bass culture in its articulation and repression. Funk’s vibrational force as it resonates throughout the juxtaposed built environment of Rio has an affective quality, in other words it influences both the mood of favelados enjoying the baile – experiencing the joy and pleasure of the bass-driven live experience – and that of the formal city that complains about the noise. Indeed, excessive noise as a legal justification for shutting down bailes goes back to the 1990s and the Lei de Silêncio («Law of Silence», 1977) (Herschmann 2005, 108). More recently, a state law in Rio that was ultimately repealed threw bureaucratic roadblocks in the way of bailes by demanding an unreasonable and impractical procedure to receive permission from the police to host a baile (URL accessed on 13.04.2012). Such rules may have impacted bailes in the formal sector, but for as long as favelas remained extralegal spaces, where the law does not necessarily apply, the events could continue unrestricted. It is only recently that the state has succeeded, through the pacification program, in physically occupying favelas and sonically pacifying them as well. For despite a law that promotes funk as culture, the word pacification, with its denotation of quelling or quieting, has finally put bailes in several high-profile favelas on lock down. It is a concern that funkeiros have not taken lightly, from proibidão that shouts «UPP filho da puta (UPP sons of bitches)» blasted live along the three sound system gauntlet of the now-pacified Mangueira baile (URL accessed on 13.04.2012), to the plaintive song by MC Tovi.

Não Entra Aqui UPP

Todas as favelas

Sempre tivemos lazer

Quem mora aqui sabe

Entende o que eu vou dizer

Tudo dando certo

Mais eu tô esperto

Não quero essa coisa de UPP

Dentro das favelas

Morador vive legal

Com muita humildade

Mas temos potencial

Estamos unidos

Canta aí comigo

O baile tá cheio e tá legal

Eu tô revoltado com Sérgio Cabral

Sem o baile aqui não vai ficar legal

Mas pra aqui ficar tranquilo

Eu já sei o que eu vou fazer

O jeito é não entrar aqui a UPP

O jeito é não entrar aqui a UPP

Se você quer saber o que vai acontecer

Primeiro vocês entram depois vou te dizer.

Eu disse ÔÔÔÔ acabo o K.Ô

Don’t Enter Here UPP

All the favelas

Always had plenty of fun

Whoever lives here knows

Understands what I am gonna say

Everything was working out

I’m smart about it

I don’t want this UPP thing

Inside the favelas

The residents were cool

Very humble

But full of potential

We’re united

Sing with me now

The baile is packed and it’s hot

I’m disgusted with Sergio Cabral

Without the baile, it won’t be cool here

But around here it’s chill

I already know what I’m going to do

The way to go is no UPP enters here

The way to go is no UPP enters here

If you want to know what’s going to happen

First come in then I’ll tell you what’s up

I said oh oh oh oh it’s over KO

By addressing residents of favelas, MC Tovi expresses an attitude that «we» know best, affirming Yúdice’s assertion of funkification, of claiming a space of their own «inside the favelas» and appealing to a notion of favela unity against the UPP. The UPP appears immensely popular among the middle and upper classes, and the mainstream media is a relentless promoter of pacification. Public opinion polls funded by the mainstream media also claim that the vast majority of residents in pacified favelas are in favor of pacification. However, the funk song presented here – whether or not it is representative of a substantial portion of favelados – posits funk as a counter-dialogue to the pro-pacification discourse, reminding any who will listen that there is a guaranteed casualty for funkeiros with the arrival of UPP. As such, for 20-odd years, the baile funk has existed as an audible experience in the affluent Rio soundscape, its wavelengths crossing the social and economic boundaries of favelas and wealthy neighborhoods. The recent state control of these cultural events, however, has relegated bailes funk to the urban periphery, where they first flourished in the 1970s and 1980s. Historically, then, one can interpret the baile funk’s presence in the Zona Sul, Centro, and Tijuca as a temporary incursion into privileged territory, which recent socio-political changes have rendered obsolete the physical links that made funk an audible reminder of the exuberant existence of Rio’s urban poor.

What Does Pacification Sound Like?

by Gregory Scruggs

The following is based on Scruggs’ experiences on August 19 and 26, 2011.

The Friday night baile in Cantagalo, the one that I have most attended since my first trip to Rio, presents a sample portrait of the pacified baile. Cantagalo is located between Ipanema and Copacabana, with access via windy Rua Saint Romain, a couple of pedestrian staircases, or the new elevator, a major federal infrastructure project that opened in 2010. Traditionally, I have climbed the staircase, a vertical portal from the gridded, high-rise city below to the irregular built environment of favelas. On Friday nights, the transition from formal to informal city is more than visual, as the bass from the baile funk further up the hill is audible as one ascends the stairs, the sound waves ricocheting through the dense agglomeration of houses and funneled down the staircase between a wall of apartment buildings before dissipating in the wider street below. Indeed, the lack of that sound used to be an indicator of something amiss, such as the time two teenagers, likely lookouts, told me that there was no baile that night «because of the war».

Under pacified auspices, the bass is once again inaudible even as one continues to ascend the road that leads to the quadra, an open-air gymnasium where the samba school rehearses and other communities events, baile included, take place. The sense of restriction was palpable, starting on the formal street far below, when out of curiosity I inquired about the baile to the two pacification police officers who were stationed at the entrance to the road that ascends into Cantagalo. They asserted that, yes, the baile would end at 2 a.m., the uncharacteristically early closing time that I had heard of from various sources. Upon arrival in front of the quadra, the street vendors who usually conducted a brisk business in beer, caipirinhas, cigarettes, energy drinks, and grilled meat skewers were nowhere in sight. Whether this was a function of the UPP or simply a market response to diminished clientele was unclear, but it was nevertheless an indication that the excitement and exuberance of the Cantagalo baile had been reduced.

To enter the baile, previously free for all – a community baile – I had to pay R$ 5 ($3 USD). The baile used to be free because the local faction paid for the event, but with the arrival of the UPP, the highly organized drug trade has been dismantled and subsequently funding for the baile must come from attendees themselves. I speculate that the baile organizers have less funding to work with as a result because there was only one sound system present, rather than the usual two – and during Carnival of 2008, a third sound system played in the street. Moreover, the soundsystem that played, Piratão («Big Pirate») had generally inferior equipment with garbled sound quality, worse than the usually raw aesthetics of live funk. They positioned their speakers to form a wall along the side of the quadra facing away from the street, which minimized the amount of sound carried outward to Cantagalo and neighboring Ipanema, as did the greatly reduced volume. Previously, I was accustomed to pounding bass that rattled through my ribcage, especially when standing right in front of the imposing wall of speakers. Bailes were always a «feelingful» experience, where music was more than just heard. It was felt, and it created emotions – excitement, awe, joy, arousal – accordingly, an embodiment of the affective nature inherent in Goodman’s politics of frequency.

At the pacified Cantagalo baile, the sound restraints appeared to have a spillover effect on the crowd, which was noticeably younger – early teens and tweens – than in previous visits. By contrast, the next night I attended the Boqueirão baile, which takes place in the formal city near the domestic airport in a large warehouse space, and is not subject to the sound or legal restrictions of Cantagalo. It was loud in the way I am used to, a ringing in your ears that lasts through the next day, and packed with an 18+ crowd.

The Piratão DJ logically steered away from proibidão as the UPP police would not have tolerated such a public challenge to their authority, and the resulting track selection was heavy on putaria. Some sonic signifiers, like gun shot samples, remained despite their association with criminal factions, and patrons pointed their index fingers in the air, mimicking pistols. Moreover, a popular proibidão MC, Menor do Chapa, was slated to perform that night. A local MC, serving as a hype man, kept promising that Menor do Chapa was on his way as the clock ticked closer to 2 a.m. With five minutes to spare, he emerged on stage and belted through a very quick medley, including the chorus to one of his big hits, «Vida Louca» (Crazy Life), which in some versions recounts the history of the Comando Vermelho gang. He sang a more generalized version with no reference to specific gangs, and after five minutes of breakneck singing departed. The DJ put on a closing track as the house lights were turned on. The patrons exited swiftly and in an orderly fashion, and a police car ascended the hill shortly thereafter, but officers did not enter the activated space of the baile.

This changing relationship between the state and favelas is exhibited through both hard and soft power. The Friday following the pacified baile, I attended the UPP Social Forum, a community meeting organized by the Instituto Pereira Passos, the urban planning arm of the Rio city government. The presentation at the Forum explained how the UPP Social is a municipal program with two objectives: «to assist with pacification by helping to legitimize it» and «to guarantee access to goods and services equal to the formal city». The forum was scheduled to begin at 10 a.m., and by 8 a.m., reminders were made over the community announcement system, a network of loudspeakers that pipes messages into the homes of Cantagalo residents. Pre-UPP, the announcements included notifications for funerals of local members of the criminal faction.

The forum took place in the quadra, the very same physical space where the pacified baile occurs every Friday and Saturday. Indeed, the Piratão sound system was in its usual spot along the wall. In the morning daylight, however, a very different amplified experience took place. City officials, together with community leaders, made short speeches on microphones broadcast over two standalone speakers atop stands. They stood on the main floor space of the quadra, rather than on the second floor balcony/stage, where funk sound systems locate their DJs and MCs. The contrast was striking in its illustration of how the same space can be activated for different uses, from the reserved, buttoned-down presentations that occurred in the morning to the loud, messy party that would start later that night. Most significant was the symbolism inherent in this contrast, the bureaucrat having supplanted the MC and the treble of tiny portable speakers having supplanted the bass of the sound system. While both MC and sound system would perform later that night, the state's daytime presence in the quadra was further evidence that a fundamental social dynamic had changed in favelas, and that funk culture was going to change as well.

Imprisoning Voices: A Second Wave of Pacification of the Favela

by Alexandra Lippman

The following is based on Lippman’s experience on December 23, 2010.

On November 2010, in preparation for pacfication, the police along with several army tanks invaded the favelas of Villa Cruzeiro and Morro de Alemão. The two-day «war» enthralled Rio. Globo’s live coverage of police shooting, barricades of cars burning, finally of dozens of young men escaping on foot and by motorcycle into the forest near the favela streamed into televisions in bars, shops, mobile phones, and cars. After the end of the «war», I heard – and overheard – many Cariocas grumble that the police must be corrupt because the lack of significant arrests. About a month after this «war», five MCs from those very areas were very publically arrested. Globo’s report showed a blurry cell phone video off YouTube of MC Ticão and MC Frank singing about how FB, the former dono (owner) of Alemão was hiding out in rival faction Rocinha. The report cut to an armed blond police woman – heavy makeup, perfect hair, cargo khakis – banging her fist on an anonymous-looking apartment door, shouting «Open up. This is the police!» MCs Frank and Ticão stood, tattooed and shirtless, blinking away sleep. The reporter’s voice intoned that the MCs were brothers and lived in the same apartment building. The camera zoomed in on a little table in MC Frank’s bedroom with a gold watch, a ring, and a few gold chains.

The female police deputy accused the MCs of engaging in cyber-crimes by using the Internet to share their proibidão funk, forming a gang (with the other MCs), associating with traffickers, and doing «marketing» (using the English word) for drugs and criminal factions.

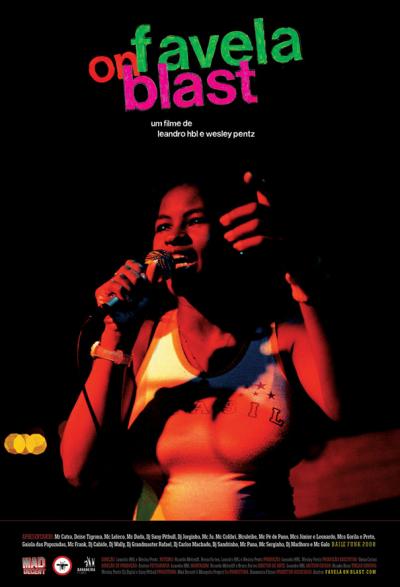

Another MC, Galo of Rocinha – one of the first to sing funk carioca in 1992 – had been arrested earlier that day on a different charge. He had been caught in a traffic blitz with a charge for marijuana possession from 1998. His case should have been unrelated to the other four MCs but was lumped into the same report. Globo dove into YouTube to show a video of Galo singing «light» proibidão in Leandro HBL and Wesley «Diplo» Pentz’s documentary Favela on Blast (2008). Globo had not contacted either director for permission to use the clip.

Two weeks after the arrest, MC Leonardo, the president of APAFUNK, organized a visit to the jailed MCs. I rode in a car along with two journalists and several funk musicians to the jail. «Men to the right. Women to the left», a jail guard’s voice boomed. Lines of women and men, whose dark skin colors and rubber Havaiana flip-flops suggested their working class status, stretched into the yard. The women stood against the building, men along the outer wall. Because of our connections, we skipped the line and walked up a staircase.

A woman and a man in gray uniforms sat behind a desk at the top of the stairs. Visitors at the beginning of the line dropped their mobile phones in a basket filled with other phones. I had heard about prisoners organizing invasions on rival territories via mobile phones. Maybe the phones were collected to prevent their being smuggled. The male guard directed us to leave our bags on the chair but to take our cameras or voice recorders. I grabbed my camera and my recording Livescribe pen.

I walked into a schoolroom with desks, a white board and childlike paintings on the walls. The MCs sat at the desks. MC Leonardo, the president of APAFunk, introduced the two Brazilian journalists as people who were working for a human rights publication. Leonardo also told the MCs that he had invited the press to a debate earlier that day.

Leonardo began interviewing the MCs, asking what was happening to them, how they were feeling, what they thought of the jail. MC Smith, a short, 24 year old, white MC with Tupac’s name tattooed twice on his right forearm began to talk. «With this political game that’s happening in Brazil now, we could expect to be jailed.» He compared his singing about violence in favelas to how Bahian axé singer Ivete Sangalo sings about Carnaval because in Bahia, Carnaval is celebrated year round. He then said, «I live in a favela that was taken by the state... one of the world’s most dangerous. I live in a favela with a high risk of violence and a base in criminality.... I’ll sing what I live and what I think. That’s freedom of expression. And it’s not only me. It’s all of us.» As he began to explain why he thought they had been arrested, the other voices in the room erupted at once into debate and agreement.

The noise probably caused a prison guard in a gray jumpsuit to burst through the door demanding our cameras and audio recorders. The two Brazilian journalists left the room for a few minutes to turn over their camera and Zoom audio recorder. When I had entered the room, I had not wanted to stand in the front of the classroom. So, I had squeezed past the desks to sit at one of the desks near MC Galo. Being the farthest from the door saved me (and my camera) from the guard’s notice.

Although everyone’s mouths had clapped shut with the guard’s arrival, soon after he left, the MCs began clapping and singing together. MC Galo sang slightly before everyone else, leading the other MCs. I began filming with my point-and-shoot camera. Lyrics begged for «protection from God. We live as if we’re in Colombia / Rocinha is like Babylon.» Galo laughed, «This is old school proibidão.» He began another song,

Liberdade meu irmão, paz e amor. É isso nada essa vida tem valor, Liberdade meu irmão isso o nada essa vida tem valor. É uma hora, um mes, um ano.... Eles estão condenados. É por isso que eu canto. (Freedom, my brother, peace and love. Nothing else in this life has value. Freedom my brother, nothing else in this life has value. It’s an hour, a month, a year they’re condemned. And this is why I sing.)

The guard burst through the door again. «Gimme your camera!» he shouted. The MCs broke off their singing. «Meeting’s over. You’re not allowed to sing», he barked, «We need to delete this». Leonardo and I hustled out of the room after the guard to an office next door. I felt myself shaking. «Delete the photos!» the guard repeated. Leonardo tried to soothe the situation by repeating that I was not a journalist.

Neither of the two guards knew how to use the camera. I deleted some of my photos. Back in the schoolroom, Leonardo told them that he was waiting for the call about when they would be freed. The MCs filed out of the room. A few gave me a kiss on the cheek or strong hug. On the night of Christmas Eve, after three weeks in jail, the MCs walked out of jail.

This arrest had been a result of the police invasion of a major complex of favelas, Morro de Alemão and Vila Cruzeiro. The publicized arrest had been a media spectacle, a dramatization of police triumphing over a criminal faction and a heavy-fisted message that the new powers of state indeed had arrived and did wield power within the recently claimed territories. The MCs – the famous voices singing of police and criminal violence – had stood in for actual members of the local Comando Vermelho criminal faction. The reports by Globo could be interpreted as media wars: an attack by the world’s fourth largest commercial network on the highly popular, independent media produced in tiny home studios in Rio’s suburbs and favelas.

Conclusion: Amplify vs. Pacify

The future soundscapes of Rio may be headed towards containment, pacified spaces, and quieter, volume controlled nights. Eliminating the baile da comunidade – or at least in its present guise – is a component of the urban redevelopment project to create a proper soundscape appropriate for a growing, global city in a country that is ambitious to become a world superpower. It is also the continuation of European, particularly Parisian, urban planning that has long had an influence on Rio (Almandoz 2002). Bourgeois social attitudes indicate that loud sonic events such as bailes simply do not happen in refined cities. The long history of strictly enforced sound ordinances in European (and some American) municipalities (Schafer 1977) is an unfortunate model for such a sonorously rich city as Rio (Labelle 2010, 51-55).

These changes, however, were not met without resistance. A group of MCs, DJs and event producers recently planned the first ever Rio Parada Funk that took place on October 30, 2011 (URL accessed on 13.04.2012). This parade was the first funk event to receive significant funding from the state, in this case the Secretary of Culture. 10 sound systems, 50 DJs, and 40 MCs were to transform the most culturally symbolic avenue downtown, Rio Branco, into the largest baile funk ever. More than two decades ago the famous samba parade moved from Avenida Rio Branco to the Sambódromo, a former city street consecrated for the performance and designed to perfectly accommodate media, tourism, and entertainment interest (Castro 2003). Use of Avenida Rio Branco for the Parada would have symbolically placed funk in the same trajectory as samba, from criminalized, poor Afro-Brazilian music to national rhythm. Funkeiros also were laying claims on rights to public space in the city by taking over one of the most prestigious corridors of the formal city.

DJ Grandmaster Raphael, one of the event’s organizers, said, «the Parada can become a yearly international attraction. Many tourists come to Rio because they want to hear funk, even more than samba». The Parada seems to share – yet flip – much of the logic behind the projects to re-sound the city in anticipation of Brazil’s emergence as a leading global superpower. Instead of pacifying the sounds of the favela, the Parada sought to amplify them.

But a week before the Parada – and after months of planning with the city government – the Institute for Historical Patrimony and National Art (IPHAN) informed the press – but not the Parada organizers – that they were going to block the event from happening on Rio Branco. Earlier, IPHAN had set a limit on the volume of the Parada, to which organizers had agreed. Yet the most popular street Carnival bloco, Cordão da Bola Preta, which last year had two million participants, has marched without sound limitation for years on the same route (Parada 2012). A popular newspaper, O Dia reported, «Iphan denies prejudice against funk and argues that the measure is to protect the listed buildings of Cinelândia, such as the Municipal Theatre, which will be open Sunday». In the second to last meeting prior to the Parada, the primary organizer asked for people to «avoid telling the press that there’s prejudice, that we’re persecuted. We’re not going to even see that people don’t like us». He and a several artists agreed that if they were to talk about being victims of prejudice, they would encourage the continuation of that discourse. Instead a DJ at the meeting suggested telling the press, «funk is equal to samba. We’re here to show that funk is culture».

Consequently, the Parada was then slated to move to Avenida Presidente Vargas, Centro’s largest monumental avenue, which has a less prestigious character as it is home to the city’s central bus and train stations, which are major hubs for commuters coming from working class neighborhoods and suburbs. It also runs east-west from Centro to the less affluent Zona Norte, whereas Rio Branco runs north-south to connect Centro with the more affluent Zona Sul. Two days later, the city government decided yet again to move the Parada. This final location, Largo da Carioca, an expansive plaza, was halfway between the original site on Avenida Rio Branco and Presidente Vargas. The new space might have been selected as an attempt to make a compromise for the Parada, but contributed to further conflicting reports on the event’s location just four days before the scheduled date.

Despite the frequent last-minute changes in venue, thousands of funkeiros filled the Largo da Carioca. Folha de São Paulo reported the Municipal Police’s estimate of 14,000 in attendance. More working-class publications O Dia and Meio-Dia reported that 100,000 attended the Parada. Ten sound systems with walls of between forty and one hundred stacked speakers rumbled funk’s increasingly localized history (Sansone 2003) for over eight hours. The first few hours began with DJs playing Miami bass, electro and American freestyle on vinyl and, in the case of one DJ, straight from YouTube. Then, DJs played montagens («montages» or medleys) on their MPCs, mixing North American roots with Afro-Brazilian drum rhythms, berimbau, and phrases (and gunshots) sampled from «bang bang» (Brazilian Western) movies. Halfway through, DJs played «laptop generation» songs, which are assembled on pirated software of FL Studio, Sound Forge and Acid, from loops exchanged over MSN. MCs, whose hits dated from 1990 to 2011, also sang on the ten stages. No fights were reported. A large sign near the main stage declared, «Funk is culture».

As the periphery becomes the center, what happens to the periphery? Will funk like samba became an «invented» national tradition (Vianna 1999; McCann 2004)? In meetings prior to the Parada, organizers stressed that DJs and MCs could not perform putaria, proibidão, or music that could cause fights such as soccer clubs' anthems. This kind of self-censorship might appear as a kind of whitewashing, an agreement to play funk that is appropriate for public (in the broadest sense) consumption. Yet, in the «headquarters of the myth of Brazilian racial democracy», funk continues to impose itself «as the creative voice of thousands of black, favela youth in the rhythm of a culture of mass» (Lopes 2011, 177, our translation). And the Parada’s organizers do assert the prominent role of funk in Rio’s soundscape through the use of public space, as civic performance carries symbolic weight (Peterson 2010), all the more so in the city of Carnival, a spectacular civic performance par excellence.

Plans for the sonic «pacification» of Rio cannot account for the unexpected actions and pushback by agents within the city. The success of Rio Parada Funk as a performance of «culture», a non-violent celebration, and power in numbers may influence the city’s discourse and actions towards bailes. Staging the largest ever baile in the center of the city indicates through enaction how funk itself has moved from the peripheries of Rio de Janeiro increasingly into the mainstream. As the Facebook page of the Rio Parada Funk boldly declared – since edited, but paraphrased here – the «batidão» (big beat) of funk has conquered even the rich youth living in beachfront gated condominiums, who cannot resist dancing when the beat drops. Even as the baile da comunidade no longer projects sound through the fortressed residences of the wealthy, funk is available in such a panoply of media that it still transgresses boundaries. Thus, although their symbolic locus in the favela is being threatened through pacification, funkeiros leveraged the mechanisms of citizenship to assert their right to the city by massively amplifying the history and current vibrancy of funk in the geographic and symbolic center of Rio de Janeiro.