Remembering Ishrat Meenai

A composition that opens a window to Jamia’s past through its echoes in the present. Jamia Millia Islamia, a central university in Delhi, celebrated its centenary year in 2020. The author introduces a conversation between different generations in his family to delve into and construct the sonic memory of Jamia, a part of the city that he calls home.

Prelude

Located close to the state border, in Southeast Delhi, Jamia refers to the institution Jamia Millia Islamia (National Muslim University). Established in Aligarh in 1920, the University shifted its campus to its present location in Okhla in 1935. Under colonial British rule, two dominant movements contributed to the birth of Jamia, «One was the anti-colonial Islamic activism and the other was the pro-independence aspiration of the politically radical section of western educated Indian Muslim intelligentsia» (Jamia Millia Islamia 2023). Jamia attracted like-minded people from across the country who believed in its ethos and were committed to its ideals.

The larger areas surrounding the University, back then, were mostly inhabited by families of the teaching and administrative staff, working in the University. This would include present-day Ghaffar Manzil, Noor Nagar, Okhla Village, and Batla House, and eventually Zakir Nagar. These colonies, along with the University campus, come under the larger locality referred to as Jamia Nagar.

My maternal grandparents, after their marriage, moved from Jaipur to Delhi in 1956. My grandfather Mohd. Naziruddin Menai was appointed as a lecturer in political science at Jamia Millia University in 1957. Since then, over the past 67 years, my mother’s family has lived in separate University accommodations before they built their own home in Zakir Nagar in 1988. Sixty-seven years is a long period of time to witness the evolution and expansion of the area surrounding Jamia.

A Sonic History

My Nani (maternal grandmother) recounts how the Yamuna, the vast river that flows through the city, was visible from the doorstep of her current house until about 30 years ago. People used to go fishing regularly. My mother speaks of sirens that were sounded to warn people of the air raids during the Indo-Pakistan War in 1971. She mentions the calls of the vendors who used to sell jaggery, sugarcane, and sweet potatoes. Many even came traveling on camel-driven carts from the nearby states of Uttar Pradesh and Haryana to sell their produce. The area was mainly forested and there were no motorized vehicles or even rickshaws. People mostly walked to get to places. As their house was being built in Zakir Nagar, to help oversee the construction, my Nani used to visit the construction site daily. She remembers how scared she used to be walking alone through particular deserted stretches in the area to get back home safely. Each of these stories carries distinct sounds which evoke and suggest a different texture or experience of time.

Zakir Nagar, named after Dr. Zakir Hussain,1 one of the main founders of the University, is a locality adjacent to the University campus and was originally planned as a private residential colony for the University’s teachers and staff. Yet over time, due to the influx of residents from Old Delhi and other areas, Zakir Nagar has become densely populated and has been structurally ghettoized over the past few decades. It is now home to lakhs of migrant population which comprises mostly Muslims working in the NCR, Jamia employees, and students studying in Jamia. Zakir Nagar, built to the edge of the river Yamuna, with unending rows of apartments, houses, and shops, has a thriving market that caters to the daily needs of the residents as well as people from the nearby localities. The main road boasts many famous restaurants and eateries, packed and bustling with people who have come to cherish a variety of dishes. I spent my childhood cycling through these unending lanes with my brother and rushing to our favorite eating spot in the evening to get warm korma, kebabs, and rotis for dinner. One can’t help but be confronted by the thought of how time has passed here and what this part of the city may have witnessed since its inception.

What connects Jamia directly to the rest of the city is its metro station named after the University. It’s accessed by students and others who make their way to and fro from work, daily. The sound of the passing metro can be heard from my home at different parts of the day.

As I get off the metro, from the platform itself, right beside the metro station, one can see the Jamia graveyard and the Batla House graveyard. Thousands of graves are laid here of people who have lived in Jamia and its neighboring areas. The Jamia graveyard is also the final resting place for my Nana (maternal grandfather) who spent over half a century serving and living in Jamia. I got to spend a brief amount of time with him. He passed away when I was still quite young. I remember entering the house and running straight to his room. He would be resting on his bed, a lamp lit up on the table next to him and his transistor playing him the news. He would embrace me lovingly as I told him about all the football I was playing.

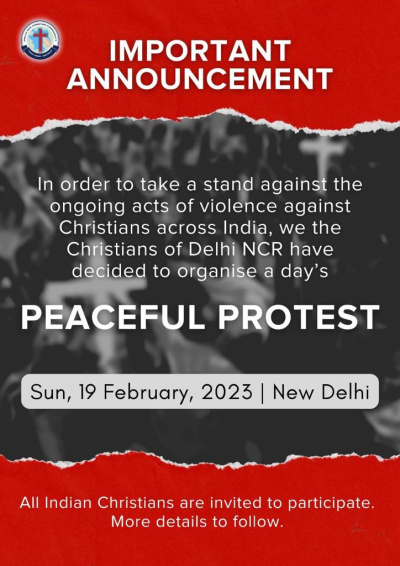

More recently, as I’ve made my way home at the end of a long day, I see the empty walls of the University under the yellow street lamps, which, for a brief period of time, held space for words of resistance during the nationwide protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019. These walls were painted over, a week into the pandemic-induced lockdown. The University was a site of political unrest following continued episodes of police brutality in response to protests against the proposed Citizenship Amendment Act. These protests brought together thousands of students, faculty, and staff of Jamia, human rights activists, along with the local population residing in Jamia to demand recognition of their fundamental rights. Debating, chanting, and singing in protest. The University echoed with sounds of police violence and of rallying cries for months.

Badr2 and Ishrat

As I walk to my Nani’s home, I wonder how this part of the city that has been home for me and my ancestral past has drastically changed for my family in the time they have lived here. For the people who have decided to make Jamia their home, how has time been punctuated for them and what can this change tell us?

It’s with the restlessness and urgency of some of these questions that I began to record conversations with my Nani. Her voice carries an intensity and intimacy that speaks of something beyond what a historical document can evoke. We spoke of many things: her childhood, her passion for writing, her life once she got married, and of course, how Jamia came to be.

This sound piece in particular, the first in the project, borrows an excerpt from a conversation I and my brother were having with Nani about her beloved husband and her love for poetry. We rustled through old documents and newspapers that had published my Nani’s writings when she was young. Both my grandparents were poets – Ishrat is my Nana’s stage name under which he composed and recited his poems, naats, and ghazals. My mother and her siblings have spent the past year trying to assemble all relevant material, speaking to relatives and family, and finding old documents to publish a book that compiles both their works of poems and ghazals together. As I listened to my grandmother recount her memories from a lifetime spent in Jamia and Zakir Nagar, I felt like this story could begin with the intensity that resides within her as she speaks of the person who got her to this city, that she built this home with, that she built her life with. It can begin with speaking about poetry, something they both shared a deep love for. This was a passionate part of their lives, something that the couple brought with them to Jamia.

Outro

The project begins with a message for my Nana and the opening of a window to Jamia’s past. Why I choose to convey this project through the medium of sound is primarily rooted in its inherent ability to evoke the imagination. I wanted to listen deeply to the city, understand it from a different dimension. A dimension that has grown to be quite close to me and one that speaks beyond the immediate plane of sight.

My time here in Jamia comes to a close soon as my mother is set to retire next year and settle down in another part of the NCR (National Capital Region). I can’t help but find a means to make my relationship with Jamia more tangible, as well as the city. To be able to look at my familial history more closely and in that exercise, be able to contribute to and document the sonic history of this neighborhood. This is a first step towards an ongoing process of inquiry.

- 1. Zakir Husain Khan (February 8, 1897 – May 3, 1969) was an Indian educationist and politician who served as the third president of India from May 13, 1967, until his death. A close associate of Mahatma Gandhi, Husain was a founding member of the Jamia Millia Islamia which was established as an independent national university in response to the non-cooperation movement. He served as its vice-chancellor during 1926 to 1948.

- 2. Badr is the author’s maternal grandmother’s pen name for her poetry.

This composition is part of the virtual exhibition «Norient City Sounds: Delhi», curated and edited by Suvani Suri.

Project Assistance: Geetanjali Kalta

Graphics/Visual Design: Upendra Vaddadi, Neelansh Mittra

Audio Production: Abhishek Mathur

Video Production: Ammar

Biography

Shop

Published on September 29, 2023

Last updated on February 21, 2024

Topics

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

Why do people in Karachi yell rather than talk and how does the sound of Dakar or Luanda affect music production?

Place remains important. Either for traditional minorities such as the Chinese Lisu or hyper-connected techno producers.

About Tunisian rappers risking their life to criticize politics and musicians affirming 21st century misery in order to push it into its dissolution.

How do acoustic environments affect human life? In which way can a city entail sounds of repression?

Snap