Country Music in Africa

Country Music has been long associated with a strong focus on its country of origin, the United States of America. When Peter Guyer and Thomas Burkhalter were filming their Contradict in Ghana, they discovered that it is very popular in West Africa. According to the Ghanaian Country musician Nii Adotey, its roots reach all the way back to Irish and Scottish settlers, and yes, also to Africa.

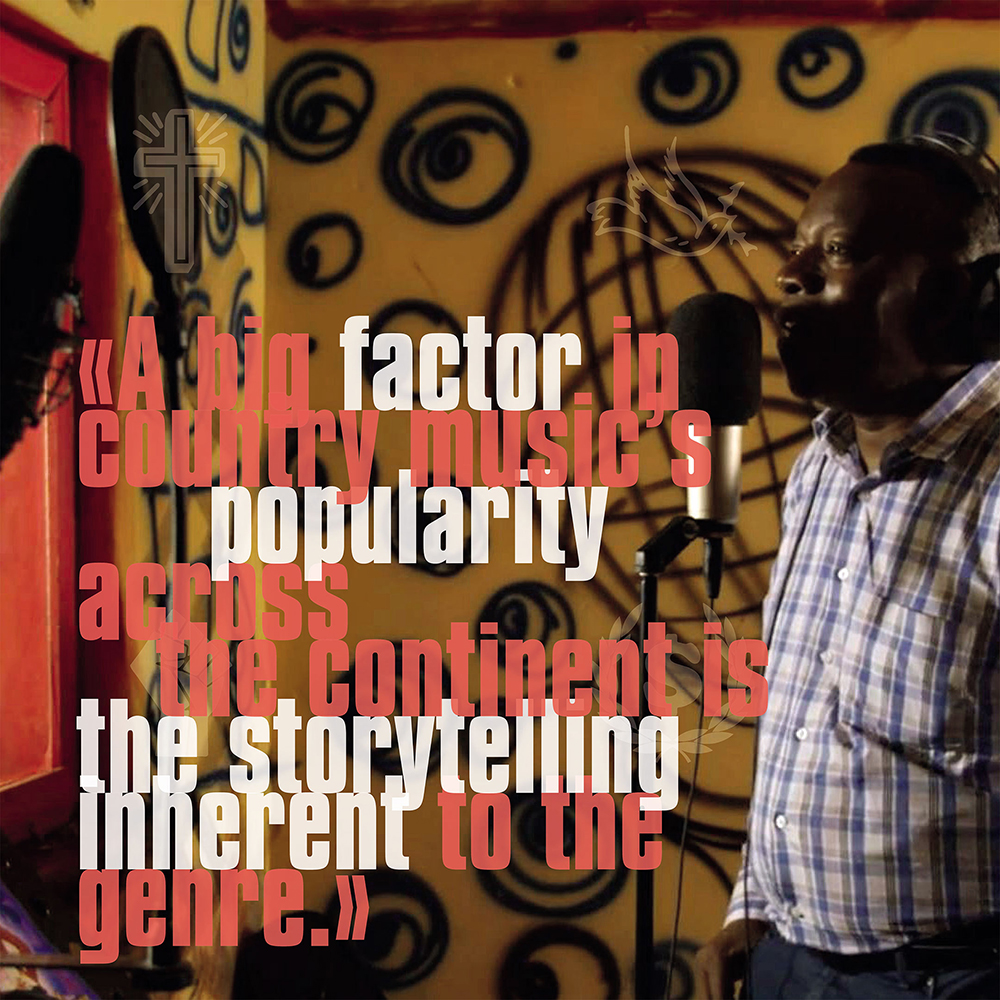

«Most of the traditional African string instruments look very much like the banjo, and I call them the ancestors of the banjo», says Samuel Allotey aka Nii Adotey, a country musician, and former military Wing Commander from Accra, Ghana. «Here in Ghana, when I say I play country music, people say it's an American genre. I agree, but when country originated in the U.S., it was a fusion of Irish and Scottish ballads, European roots music, and early African American musicians playing the fiddle and the banjo. It's a melting pot of different cultures, with everyone adding a flavour to it.»

Like Allotey puts it, the connotations that hang around the genre, and the visual language of Western films (cowboys, frontier saloons, dawn shootouts, etc.) are coded as iconically American, which is a red herring of sorts. Through the connection between the signature country music guitar playing style, and it's origins in the techniques associated with the banjo, an instrument brought to America from Africa – as with its roots in Irish, Scottish and Celtic fiddle tunes and folk songs – country music also has a connection with Africa. As such, throughout countries like Kenya, Nigeria, Côte d'Ivoire, and Ghana, it has long been practised by a select number of musicians like Allotey.

American country music first arrived on the African continent in the 1920s/1930s. You can hear some examples of local recordings made in the 1950s in Zimbabwe, Kenya, and South Africa on Olvido Records excellent Bulawayo Blue Yodel compilation. However, the real breakout moment with the general public in many African countries came with the arrival of the smooth, harmony-heavy Nashville sound in the 1960s. It was an aesthetic that continues to speak to the audience on a deeper level, with many radio stations hosting regular, longstanding country shows with a focus on the United States.

Alongside this quality, another big factor in country music's popularity across the continent is the storytelling inherent to the genre. «I have a love of stories, and it's a very nice medium for getting stories across», he says. It's more than just stories however, it's the characters, as NPR's Gwen Thompkins described them in 2007, «...the gamblers and the highwaymen, the hand wringing mothers and the cock-sure sons, the Rubys, the Lucilles, the Jolenes, the grievous angels and the folks who just ain't no good».

The stories are working-class stories, populated by working-class characters, and their themes of love, heartbreak, tragedy, and a relationship with «the land» translate across borders with ease. Like Henry Makhoka, head of programming at the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation told Thompkins for NPR in 2007, «Most of the country music we play talks about country life, the farm life and so on. That kind of environment was abundantly available where I was born.»

«People Always Demand What They Know»

Like many African country music musicians and fans, Allotey remembers first hearing country music on the radio in Ghana the late 1970s and early 1980s, with Kenny Rogers's enduring anthem «The Gambler» serving as his entry point, and quickly followed by the music of Dolly Parton, Don Williams, and ground-breaking African American country artist Charley Pride. The story of Allotey's introduction to country music is almost identical to that of Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire duo Jess Sah Bi & Peter One, who experienced massive popularity across West Africa in the mid-to-late 1980s, before relocating to the U.S., where they have been recently touring following the reissue of their classic album Our Garden Needs Its Flowers through Awesome Tapes From Africa in 2018.

Allotey lived in the U.S. for a time as well. It wasn't for the purposes of performing music, but the experience gave him the inspiration that would later galvanise him. «I studied in America for a year while I was in the military», he remembers. «A friend of mine and I, who loved country music as well, we drove from Alabama to Nashville, Tennessee to attend the Grand Ole Opry (a legendary weekly country barn dance). It made quite an impression on me.»

Allotey has spent the last three years building his profile as a country artist in Ghana through recording songs and performing around the capital. Despite the support U.S. country music receives on local radio, finding local musicians and fellow acts to play with has been challenging. «I think it's a supply and demand thing», he says. «People always demand what they know, and because there were no local artists in the field, they would always pick a CD by a foreign artist.» That said, he's working to change things, as are other artists across the continent like Nigeria's Ogak Jay Oke, and the aforementioned Esther Konkara and Dusty & Stones. «It takes a while for people to notice you. The world is crowded. You have to keep going. It's about endurance. You keep searching for gold until you hit a rock.»

More African Country Artists

Two cousins from Swaziland taking African Country music to America and Europe

Elvis Otieno aka Sir Elvis, the King of Kenyan Country Music

A Nigerian 1980s pop star with a spectacular command of the Nashville sound

Nigeria's first lady of African Country

This article has been produced in the course of the film project «Contradict – Ideas for a New World» by Peter Guyer and Norient founder Thomas Burkhalter (Switzerland/Ghana 2020). More info on www.contradict-film.com.

The film «Contradict» by Peter Guyer and Thomas Burkhalter was officially selected at the Norient Film Festival NFF 2021. See full program here.

Biography

Links

Published on November 12, 2019

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topic

From westernized hip hop in Bhutan to the instrumentalization of «lusofonia» by Portuguese cultural politics.

Special

Snap