Tongues and Borders Are Immutable

Lacking a common language is not always an obstacle to communication. It can help to build new connections without preconceptions. An essay inspired by the film In your Eyes, I See My Country, in which two Israeli musicians travel to Morocco.

→ Check all articles of this special

→ Download PDF with introduction and table of contents

As a Hebrew speaker I hear traces of semitic language in Arabic. As a practising Jew, I hear echoes of Arabic sounds in the liturgies I am familiar with. But this loose affinity does not allow me to distinguish different variants of Arabic. What intrigued me about the documentary In Your Eyes, I See My Country was the extent to which the protagonists Neta Elkayam and Amit Haï Cohen are fluent in Moroccan Arabic specifically. On their trip to Morocco it seems as though Neta sometimes lacks confidence interacting in Arabic, to the extent that she needs things re-explained to her.

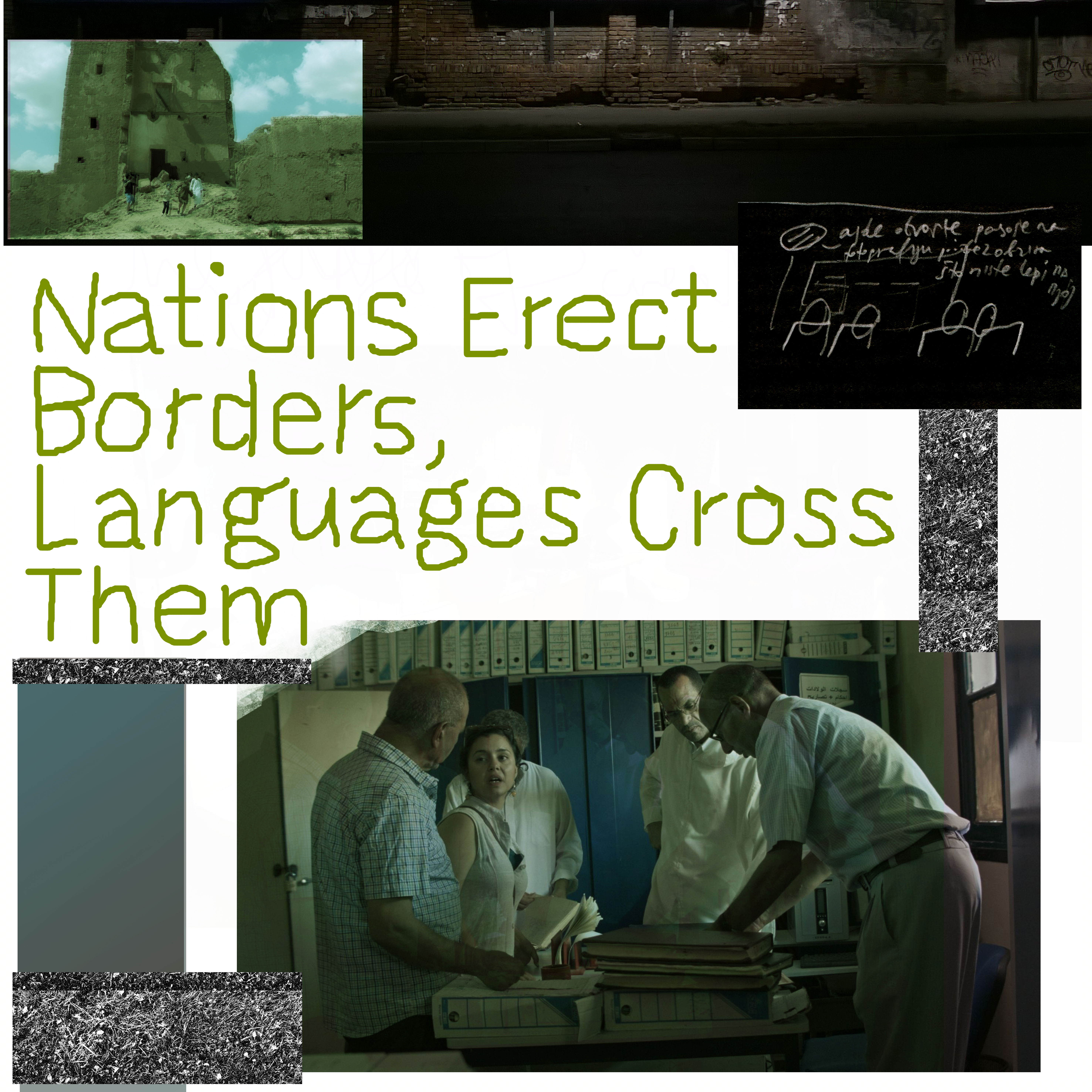

Nations Erect Borders, Languages Cross Them

This is where subtitles make the film opaque. They do not indicate which language is spoken at any time. I don’t know whether Neta’s Arabic is standard Arabic (meaning she is uncomfortable interacting in Moroccan Arabic), Moroccan Arabic (meaning she is uncomfortable interacting in standard Arabic), or if specific local dialects of Moroccan Arabic are unfamiliar to her.

Yet sometimes a lack of knowledge of a language can offer its own insights. When a viewer cannot tell what language is being spoken, it can be easier to watch without preconceptions concerning what it means to speak a certain language at a certain place and time. There are moments in the film when it isn’t clear whether one sees Arabic being spoken in Israel or Hebrew spoken in Morocco. This is, I suspect, part of the point: nations erect borders, languages cross them. By making the connection between a piece of land and its language unclear, In Your Eyes, I See My Country questions the supposed immutability of tongues, and of national boundaries.

Origin Doesn’t Matter

The same is true of the music in the film. To someone not well-versed in Maghrebi or Middle Eastern music, it is rarely clear what style is being played, how novel the songs and their lyrics are, how innovative or traditional the instrumentation may be. We see Neta performing love songs and praise songs to Jewish rabbis; playing with orchestras and in intimate jam sessions; or accompanied by her husband on banjo and chanting with other singers.

When Neta and Amit jam with Moroccan musicians, it is hard to guess what musical borders are being crossed. Were the encounters a form of reaching out between different musical languages, or were they a (re)affirmation of a common language that was artificially sundered? What I do know: the confusion of languages is not an obstacle to the building of relationships. Rather, Neta, Amit, and the Moroccans they meet are willing to transform communication barriers into a new language of respect. In this sense, not speaking the same language can be a starting point for reconciliation rather than an obstacle to it.

The film «In Your Eyes, I See My Country» by Kamal Hachkar was officially selected at the Norient Film Festival NFF 2021. See full program here.

This text is part of Norient’s essay publication «Nothing Sounds the Way It Looks», published in 2021 as part of the Norient Film Festival 2021.

Bibliographic Record: Rhensius, Philipp. 2021. «Editorial: NFF 2021 Essay Collection.» In Nothing Sounds the Way It Looks, edited by Philipp Rhensius and Lisa Blanning (NFF Essay Collection 2021). Bern: Norient. (Link).

Biography

Published on December 04, 2020

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topic

On new cultural implications of Meme Music, and how commnunication is more and more a result of power relations disguised in social networks.

Snap