Validation, Ignoration, Rosication: An Italian Tragicomedy

In this interview, filmmaker Mike Calandra Achode and DJ and music producer Francesco Cucchi recount their first-hand experience with the three attitudes the Italian cultural sector takes on to defend itself from experimentation, diversity, and multicultural avant-gardism.

To better express their experience, Mike and Francesco, who grew up in Rome and are currently based in London, coined the terms rosication and ignoration. The first is the anglicized version of the regional expression «rosicare», mainly used in Rome and the Lazio region, which can be translated as «to be eaten away/gnawed by envy». The latter stands for «indifference, neglect». With validation, these three stages represent a post-Dantesque journey of the Italian creative mind, at home and abroad.

... For We Had Lost the Path that Does not Stray

Mike Calandra Achode is a documentary filmmaker, designer, lecturer, and founder of Crudo Volta, a visual project documenting the development of contemporary musical scenes of the African diaspora. Francesco Cucchi is a DJ and label owner. He founded Gqom Oh!, a label that shines a light on the music scene from Durban, South Africa.

Their background, life experiences, and interests are different. Francesco is a white Italian man who at some point in his life developed a deep interest in gqom music and decided to explore it. He became the «ambassador» of gqom music1 and in some ways represented Italian innovation in the world. Mike was born in Benin and moved to Italy when he was eight years old. Today, while he feels he is «still a guy from Magliana» (S/Confini 2020) — the neighborhood in Rome where he grew up — his relationship with his «Italianness» is problematic. When asked, Mike says, «I don’t reject my Italian identity, nor my European one, but I identify as a Beninese man».

The shift from identifying himself as an Afro-Italian to a Beninese designer changed his approach to his own projects: «When I identified as an Afro-Italian with African origins, my designs had a particular style, intention, and a specific aesthetic (...) my main goal was to create a type of safe-space that would connect Italians and young people from the so-called seconde generazioni2 to create a relation based on mutuality.» When he started identifying himself as a Beninese artist, his perspective changed. In fact, all of his references are Beninese and above all Dahomey (Benin pre-French Colonization) and the kingdoms/empires of Western Africa.

What unites Francesco and Mike is a long friendship and their current home, London. But most of all, they found themselves experiencing the Italian cultural sector’s provincialism, which confined them to a microcosm of the order of Dante’s world.

You Are Rosicating the Hell Out of Me

At the bottom, in the Inferno, there’s the state of rosication, where you are envied for your success — which is the greatest sin you could possibly commit. Francesco Cucchi recounts that before being validated as an artist for his experience in London, he had never been considered as a music professional in Italy. In London, contrarily, he felt more valued and started his journey of self-discovery and awareness on various topics including what he refers to as the «Italian music identity». His DJ sets in London were all sold out, but in Italy «when you’re successful abroad they either value or envy you. It’s either validation or rosication».3 When he was asked what he has experienced he said: «Precisely both of them. And there’s even been someone who started ignoring me because I became cool».

Floating in a Purgatorial Ignoration

Ignoration corresponds to the purgatorio, the most tedious state as it is a never-ending limbo where you have to atone for your sins without knowing whether you will ever make it to the next level: The Paradiso. This exemplifies Mike’s entire experience as a filmmaker in Italy. His documentary was ignored altogether: «More than rosication, [in my case] I think it’s a matter of ignoration. I had a screening in Turin in 2016 of my other documentary Woza a Taxi. It was at the Club to Club Festival. This was the only type of interaction in relation to my documentaries I got», he says. «And I must admit, at that time we did have international press coverage: I’ve talked to American, Canadian, French, German, Spanish journalists. This interview is the first time in five years that I get to sit down and talk about my visual project in Italian in a more articulate way. Tomorrow I’m gonna go to Turin4 and in April to Naples.5 And all of this pushes me away from Italy. Also seeing the reception I get here, focusing more on my audience, that is fundamentally made of young Africans who are part of the African diaspora, I realize that my place is somewhere else, outside of Italy.»

Take Me Down to Validation City

The Paradiso is a microcosm where you may end up if you receive validation, which entails having success abroad, but even this may not be sufficient, as Mike’s experience shows. Pursuing recognition outside of Italy in order to be considered worthy of success back home is a path countless Italians have followed even before Italy became a nation in 1861.

The history of pizza is a classic example: The Italian dish par excellence became widely known in Italy only after it received validation in the U.S. In the late 19th century it was exported to North America by Neapolitan immigrants. At the time it was known only in some areas of Southern Italy, while the rest of the nation totally ignored its existence. In the U.S. it became remarkably popular, to the extent that during World War II American soldiers in Italy started asking for it. With the increase of international tourism, pizzerias began to open everywhere in the country.

This story prompted professor of anthropology Agehananda Bharati to coin the term «pizza effect», which indicates the phenomenon that occurs when an element of a culture is more fully embraced abroad, in some cases even transformed, and then is re-imported in the culture of origin.

Midway Upon the Journey of an Artist

A noteworthy element in this story is that Francesco was able to undergo all three attitudes: He explains his work was ignored, envied, and validated; while Mike’s never received the recognition it deserved. Despite the project being sponsored by a big platform such as TIMvision,6 in Italy, Mike got stuck in the ignoration circle. When asked why he thinks this is the case he said:

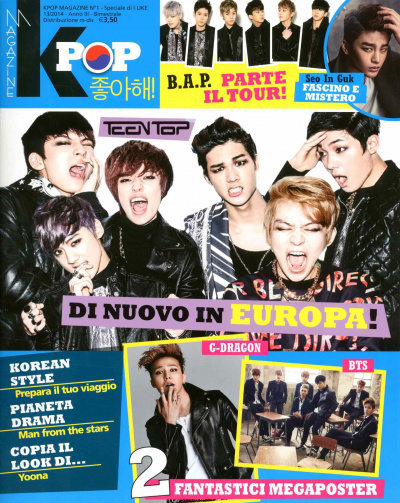

«I believe there are a number of reasons. On the one hand, this is the result of a continuous alienation of African identities in Italy, if not in the West. This identity is validated only when it is introduced through a ‹white channel› that makes it in some ways less distant and, precisely, less alien. So much so that they called Francesco ‹the ambassador› of gqom. A terrible title, at least for a musician. On the other hand, the only Blackness accepted in Italy at the moment is an Afro-American Blackness. In Italy, I resolved that the so-called ‹Blackness› imported by the American industrial-military machine from the post-war period onwards is seen more as an accessory of ‹coolness› than anything else. A bit like wearing a pair of jeans. And so here is that the various coolness magazines in Italy do not know what to do with ‹African› coolness and its narratives. They don’t know how to treat it editorially. Because they alienate African people despite being interested in Blackness».7

The Farewell that Moves the Sun and the Other Stars

The journey to success for ground-breaking musicians in Italy is filled with obstacles and missteps. The solution for an uncertain future is given by leaving the country entirely. Yet, even the achievement of success abroad could be frowned upon back home.

While this journey of penance might end with the attainment of the state of Paradiso for some Italian musicians, the reality for others might vary. Ignoration is the path destined to those who differ from the pre-inscribed categories in the Italian musical sphere, those deemed too defiant and unconventional. Those who do not conform to certain set styles and musical forms risk endlessly roaming in the selva oscura (shadowed forest) and should perhaps leave their hopes of being acknowledged in Italy altogether. To use Dante’s own cautionary words, «Lasciate ogne speranza o voi ch’intrate» («all hope abandon, ye who enter in»).

- 1. Quoting Last.fm: «Gqom is a genre of electronic dance music that emerged in the early 2010s from Durban, South Africa. It developed out of South African house music, kwaito and hip-hop. Unlike other South African electronic music, gqom is typified by minimal, raw and repetitive sound with heavy bass beats but without the four-on-the-flour rhythm pattern.»

- 2. Children of migrants and adopted children living in Italy.

- 3. «Rosicare» can be translated as «to feel envy, to be eaten away by envy». It’s a regional expression, mostly used in the Lazio region, where Rome is. In this case Francesco anglicized it to «rosication».

- 4. The interview was recorded on February 22, 2020. The following day there was a screening at See You Sound in Turin.

- 5. This screening was cancelled due to coronavirus restrictions.

- 6. So big it co-produced the International TV series «My Brilliant Friend», based on the bestseller by Elena Ferrante, with HBO and RAI.

- 7. Mike Calandra Achode, phone call to authors, November 3, 2020.

List of References

Biography

Biography

Links

Shop

Published on April 22, 2021

Last updated on April 09, 2024

Topic

Does the global appropriation of kuduro exploit or reshape the identity of Angolans? How are «local» music genres like guayla sustained outside of Eritrea?

Special

Snap